Happy Chinese New Year! For Chinese throughout the world, the first new moon that appears between January 21st and February 20th marks the lunar new year, the end of winter and the beginning of the spring season. It’s one of the most important holidays in Chinese culture whether it’s known as Chinese New Year (Taiwan), Spring Festival (People’s Republic of China), Tet (Vietnam), Losar (Tibet), Seollal (Korea) or simply the Lunar New Year. Traditionally a 10-day festival, it’s a time to honor both deities and ancestors.

According to legend, it started with a mythical beast called the Nian. During the Spring Festival, it would eat villagers, especially children, during the middle of the night. One year, an old man appeared before the villagers and said that he would get revenge on Nian. While the villagers went into hiding, he stayed the night putting up red papers and setting off firecrackers. The next day, when the villagers returned, they saw that nothing had been destroyed. They assumed that the old man must have been a deity showing them that Nian was afraid of the color red and loud noises.

According to legend, it started with a mythical beast called the Nian. During the Spring Festival, it would eat villagers, especially children, during the middle of the night. One year, an old man appeared before the villagers and said that he would get revenge on Nian. While the villagers went into hiding, he stayed the night putting up red papers and setting off firecrackers. The next day, when the villagers returned, they saw that nothing had been destroyed. They assumed that the old man must have been a deity showing them that Nian was afraid of the color red and loud noises.

This became a tradition for the villagers. As the new year approached, they would wear red clothes, hang red lanterns, place red good luck images on windows and doors, and use firecrackers and drums to frighten away the beast. Nian never came to the village again.

Records of the first New Year celebration can be traced to what the Chinese call the “Warring States Period” (475 BC – 221 AD). As the ritual evolved and spread through succeeding dynasties, it incorporated the practices of thoroughly cleaning one’s house prior to the start of the new year, worshipping one’s ancestors, sending new year’s cards, visiting friends and acquaintances, wearing new clothes, eating auspicious food, giving gifts, and giving children lucky money.

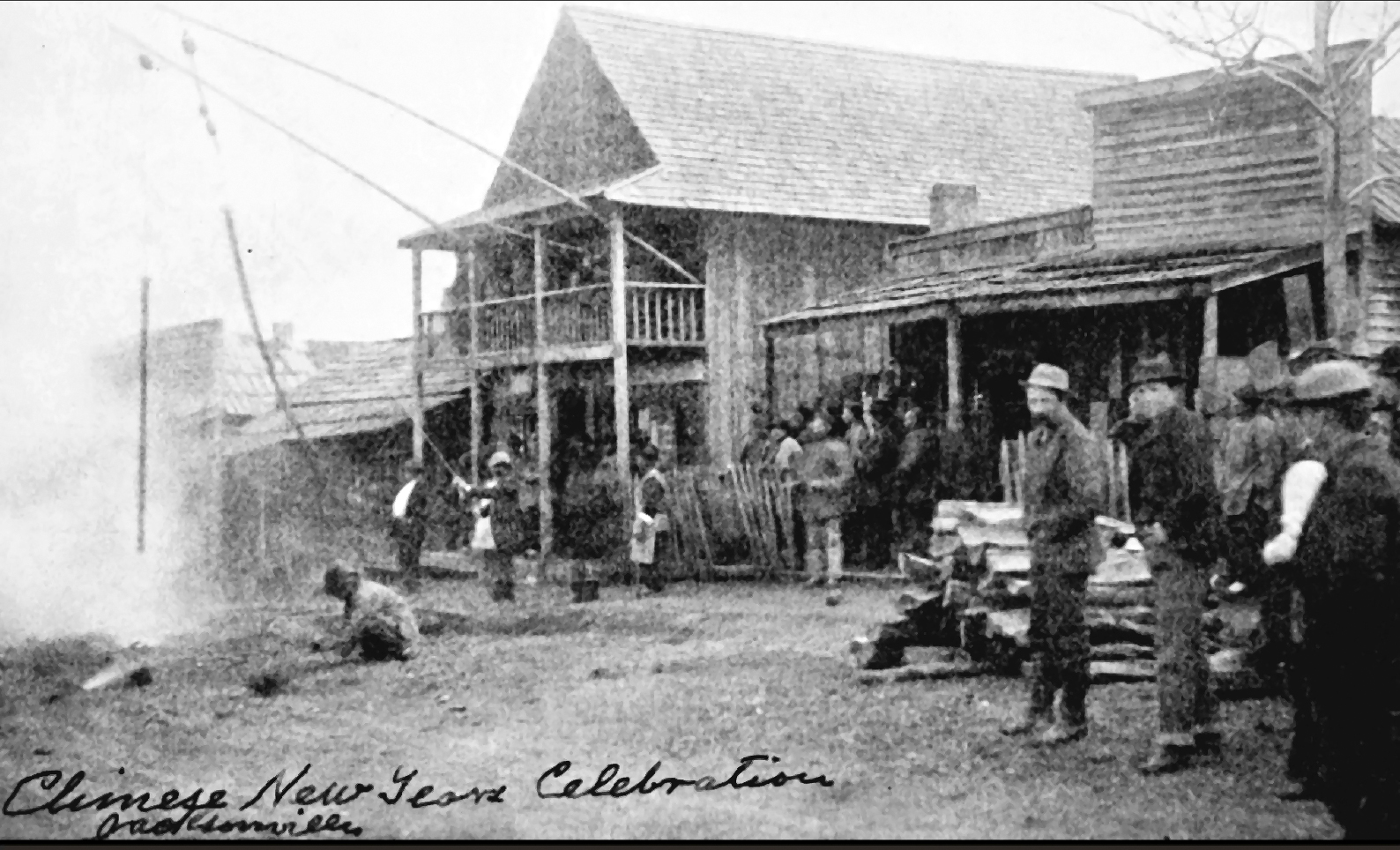

Jacksonville’s own Chinese population would have incorporated many of these traditions. Did you know that Jacksonville housed Oregon’s first Chinatown? By the early 1870s several 100 Chinese lived in Jacksonville, primarily on West Main between South Oregon and 1st streets in the ramshackle buildings that had been the mining camp’s original “business district.”

However, small Chinese communities such as Jacksonville had neither a temple nor a priest. Because of costs, the lengthy celebrations such as Chinese New Year were reduced from the typical 10-day period to as few as four days. But the town’s Chinese residents made up with intensity what they lacked in duration, and, in preparing for the New Year, the entire Chinese community was mobilized. Dwellings were cleaned to sweep away any ill-fortune and to assure good luck. New clothing was purchased or sewn, hundreds of dollars were spent on firecrackers, and before the event began all personal debts had to be repaid. Large amounts of food and meat were purchased; incense tapers, and quantities of red-tissue prayer papers were prepared.

The day would begin with a fusillade of firecrackers to drive away evil spirits. A procession to the Chinese section of the cemetery would be followed by hired wagons carrying quantities of food prepared for the event. Prayer papers were strewn on the road ahead of the mourners. At the cemetery, the grave sites were cleaned, and the cooked hogs and chicken dishes along with cups of wine or brandy would be set on the ground for what was known as “feeding the dead.” When the ceremony ended, the food was then taken back to town leaving the deceased to enjoy the “tempting aroma.”

The day would begin with a fusillade of firecrackers to drive away evil spirits. A procession to the Chinese section of the cemetery would be followed by hired wagons carrying quantities of food prepared for the event. Prayer papers were strewn on the road ahead of the mourners. At the cemetery, the grave sites were cleaned, and the cooked hogs and chicken dishes along with cups of wine or brandy would be set on the ground for what was known as “feeding the dead.” When the ceremony ended, the food was then taken back to town leaving the deceased to enjoy the “tempting aroma.”

In the Chinese quarters empty chairs were set up, the musicians began to play, and the great feast began. The food, much of it imported from Hong Kong, featured bean-curd cakes, varieties of exotic dried fish, clams, and mushrooms, along with noodles and cabbage. Rice or apricot wine was the drink of choice, but brandy was also popular. The feast would be accompanied by the music of Chinese fiddles, barrel drums, and gongs, intended to entertain the deceased.

Local children would be drawn by the noise and line up for Chinese candy and sweets and of course a parading dragon! For the Chinese, the New Year’s festivities were a high point of their lives. While the children may have loved the celebration, many Jacksonville residents viewed it with distaste, greeting it with ridicule and distaste.

From the white perspective, almost everything was wrong: firecrackers scared their horses, cooking of the meats created a “great stink,” and the food, although prepared with great care, was deemed repugnant. References to Chinese New Year in the town’s two weekly newspapers were invariably negative. The press judged the events as an “affliction upon our residents,” occasions for “gobbling vast quantities of roast pig and chicken, smoking opium, drinking very bad brandy, and burning any amount of firecrackers, to the accompaniment of heathenish sound by gong and cymbal, and pig-squealing screeched from bamboo banjos and one stringed fiddles.”

From the white perspective, almost everything was wrong: firecrackers scared their horses, cooking of the meats created a “great stink,” and the food, although prepared with great care, was deemed repugnant. References to Chinese New Year in the town’s two weekly newspapers were invariably negative. The press judged the events as an “affliction upon our residents,” occasions for “gobbling vast quantities of roast pig and chicken, smoking opium, drinking very bad brandy, and burning any amount of firecrackers, to the accompaniment of heathenish sound by gong and cymbal, and pig-squealing screeched from bamboo banjos and one stringed fiddles.”

But how Southern Oregon “welcomed” the Chinese is another story and a disturbing one. And by the late 1880s, the noisy, exuberant Chinese New Year celebration was largely a thing of the past.

We realize that, by now, most of you may be asking “where do all the animals come in?” The animals are basically Chinese zodiac symbols.

Although modern-day China uses the Gregorian calendar, the traditional Chinese calendar governs holidays, such as the Chinese New Year. It’s a “lunarsolar” calendar, based on astronomical observations of the Sun’s longitude and the Moon’s phases. A common year has 12 months and a leap year has 13 months. An ordinary year has 353–355 days while a leap year has 383–385 days. Days begin and end at midnight, and months begin on the day of the new moon.

Although modern-day China uses the Gregorian calendar, the traditional Chinese calendar governs holidays, such as the Chinese New Year. It’s a “lunarsolar” calendar, based on astronomical observations of the Sun’s longitude and the Moon’s phases. A common year has 12 months and a leap year has 13 months. An ordinary year has 353–355 days while a leap year has 383–385 days. Days begin and end at midnight, and months begin on the day of the new moon.

However, each year combines two components—a 10-year celestial aspect and a 12-year terrestrial branch based on the zodiac. Most of us are familiar with the terrestrial branch which features animal names—rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar or pig. However, both celestial and terrestrial components are in a 60-year rotation, and the combination of the two in the year that an individual is born is supposed to determine his or her future.

The Lion Dancer, shown in our Chinese New Year image, while not part of the Chinese zodiac, symbolizes power, wisdom, and superiority. People perform lion dances at Chinese festivals or on big occasions to bring good fortune and chase away evil spirits. The lion dance is one of the most important traditions at Chinese New Year.

For more information about current and past Jacksonville Chinese New Years visit the Southern Oregon Chinese Cultural Association website (SOCCA) at https://www.soccachinesenewyear.org/