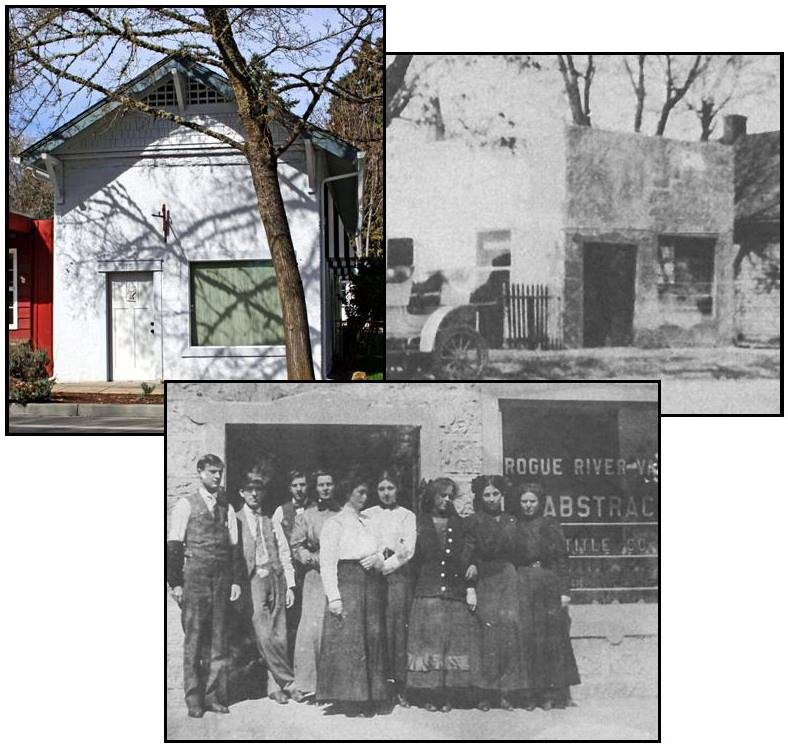

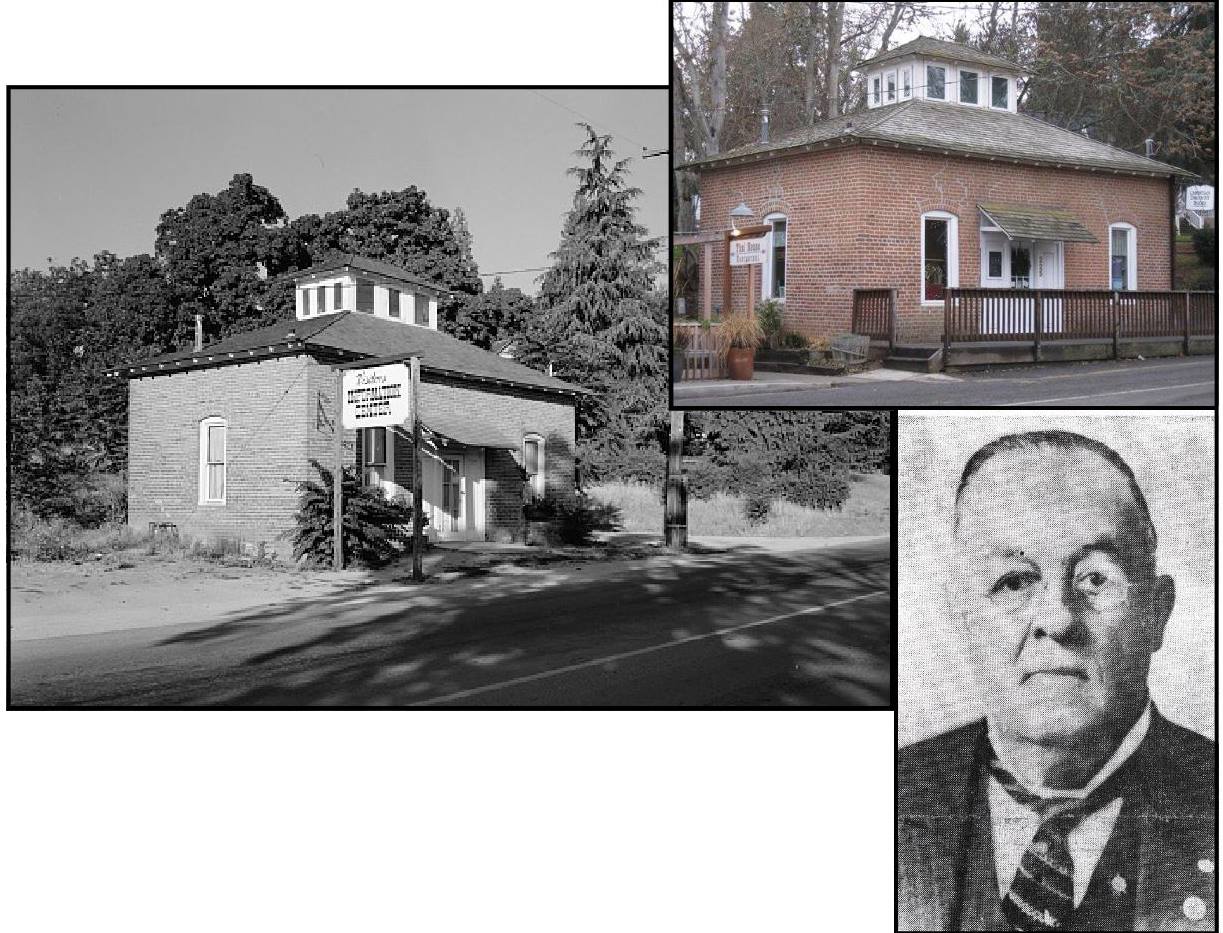

Abstract Company Concrete Building

The small building at 215 North 5th Street has in recent years been a perfumery and an antique store among other uses. However, it was constructed around 1915 for the Rogue River Valley Abstract Company, what we would today call a real estate title business. It is believed to have been the first reinforced concrete building constructed in Jacksonville, Oregon. The building immediately to the north, now the Magnolia Inn, was built around the same time for the Rogue River Sanitarium. When the County seat was moved to Medford in 1927, the Abstract Company appears to have moved as well and the building was converted into the Sanitarium’s laundry. It apparently remained so for a number of years since the laundry plumbing still existed well into the 1970s.

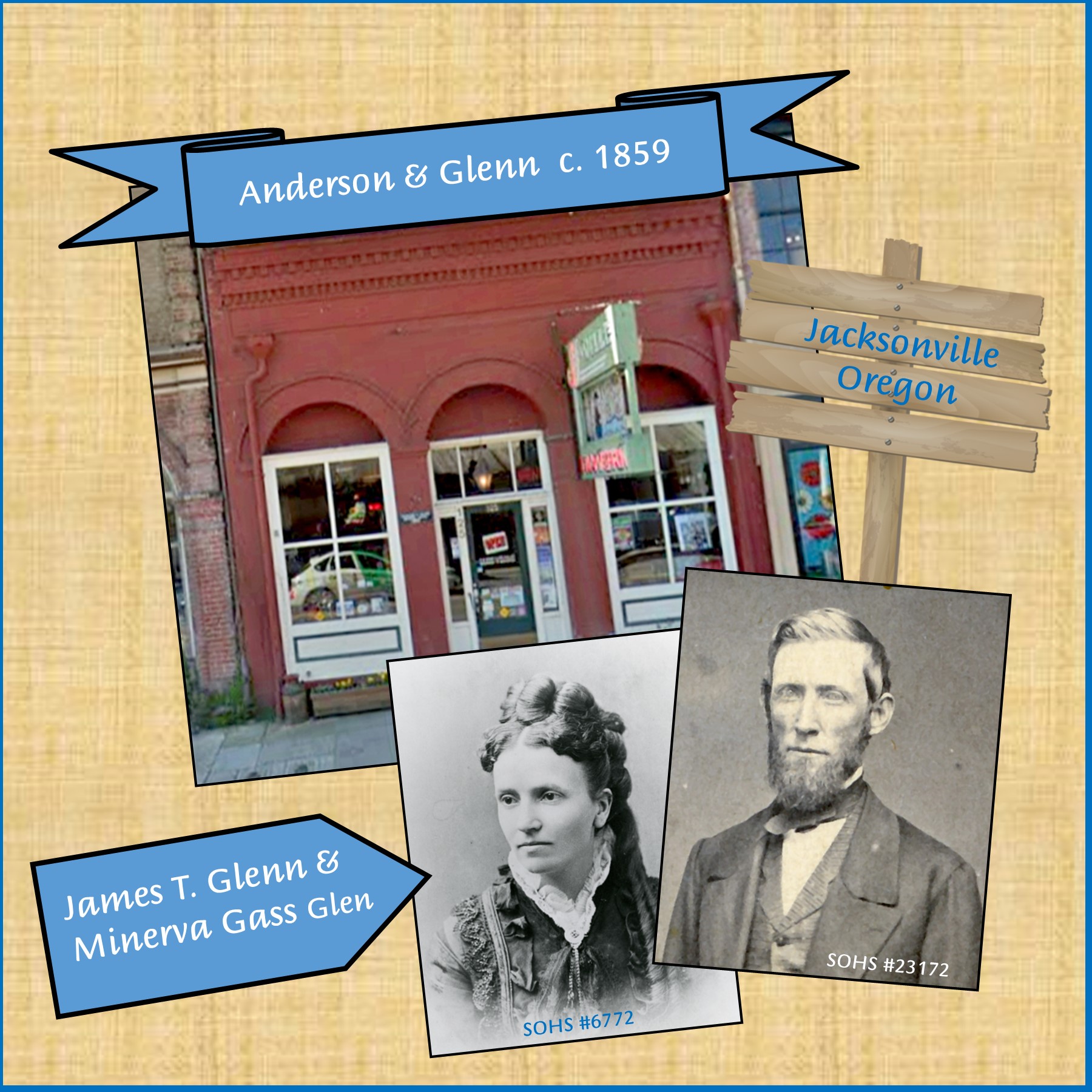

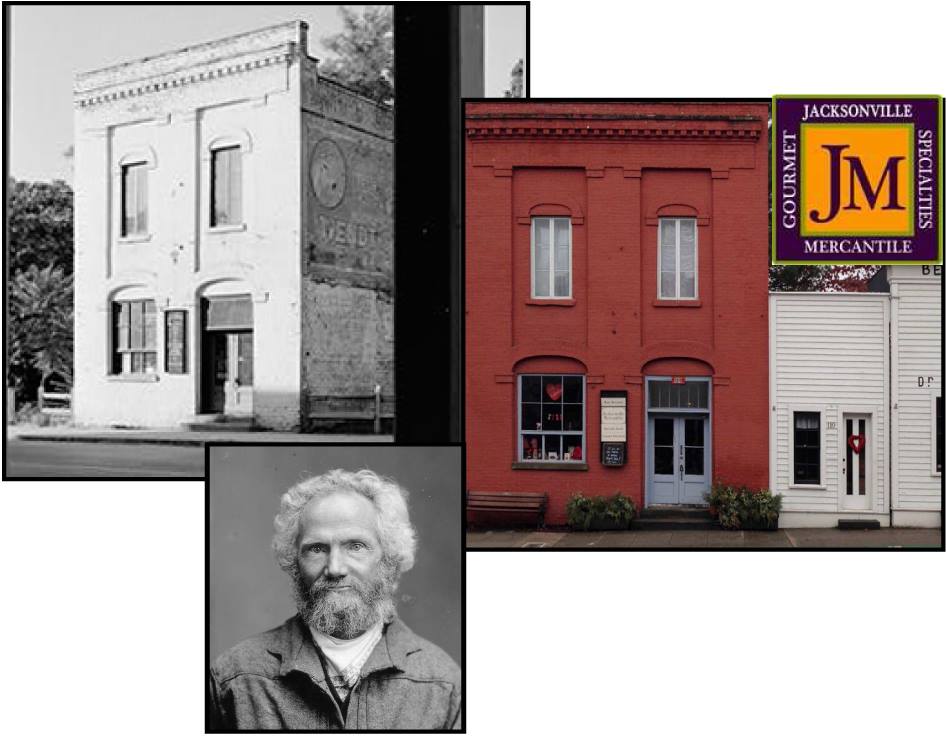

Anderson & Glenn General Store

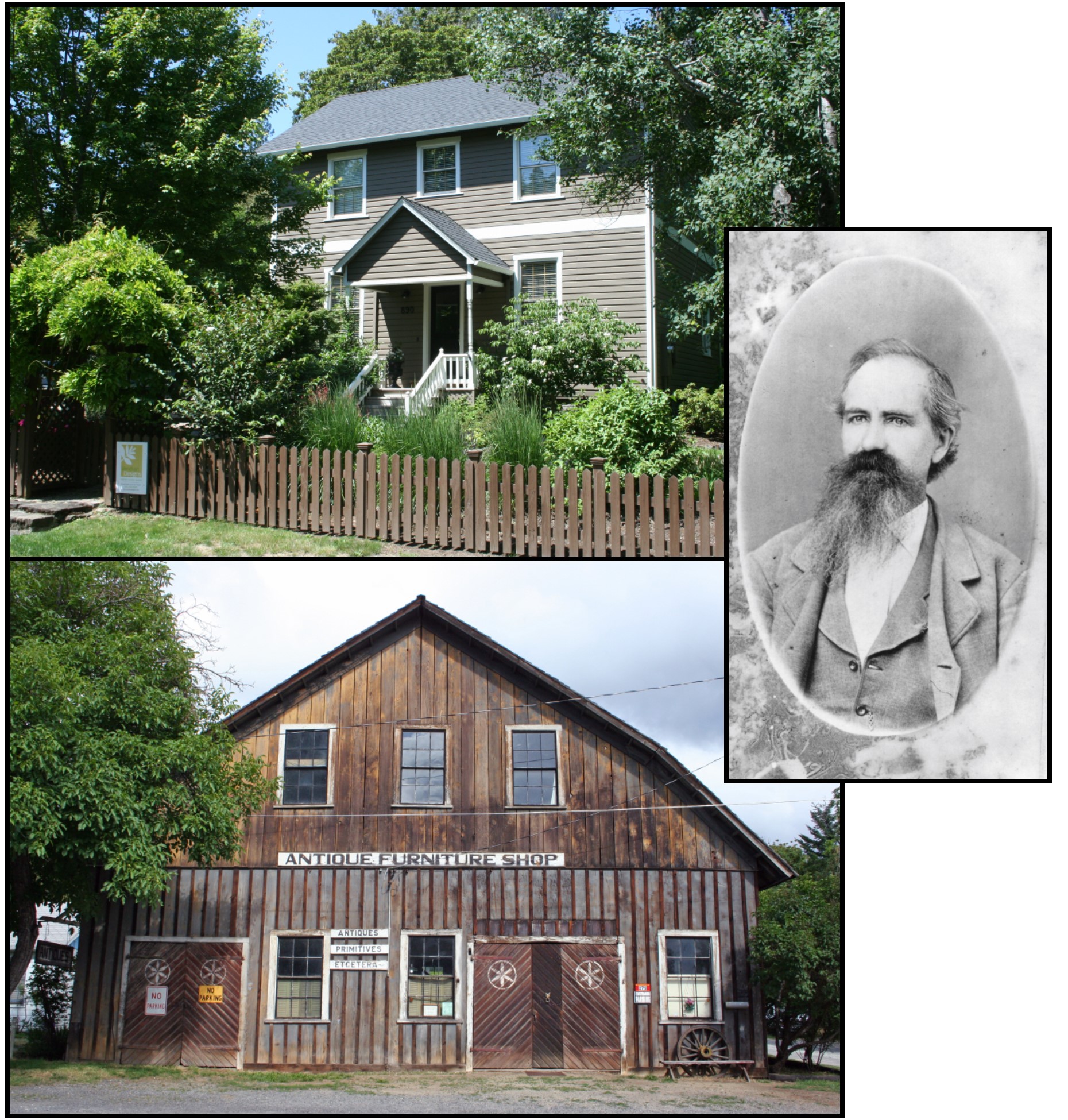

Applebaker Barn

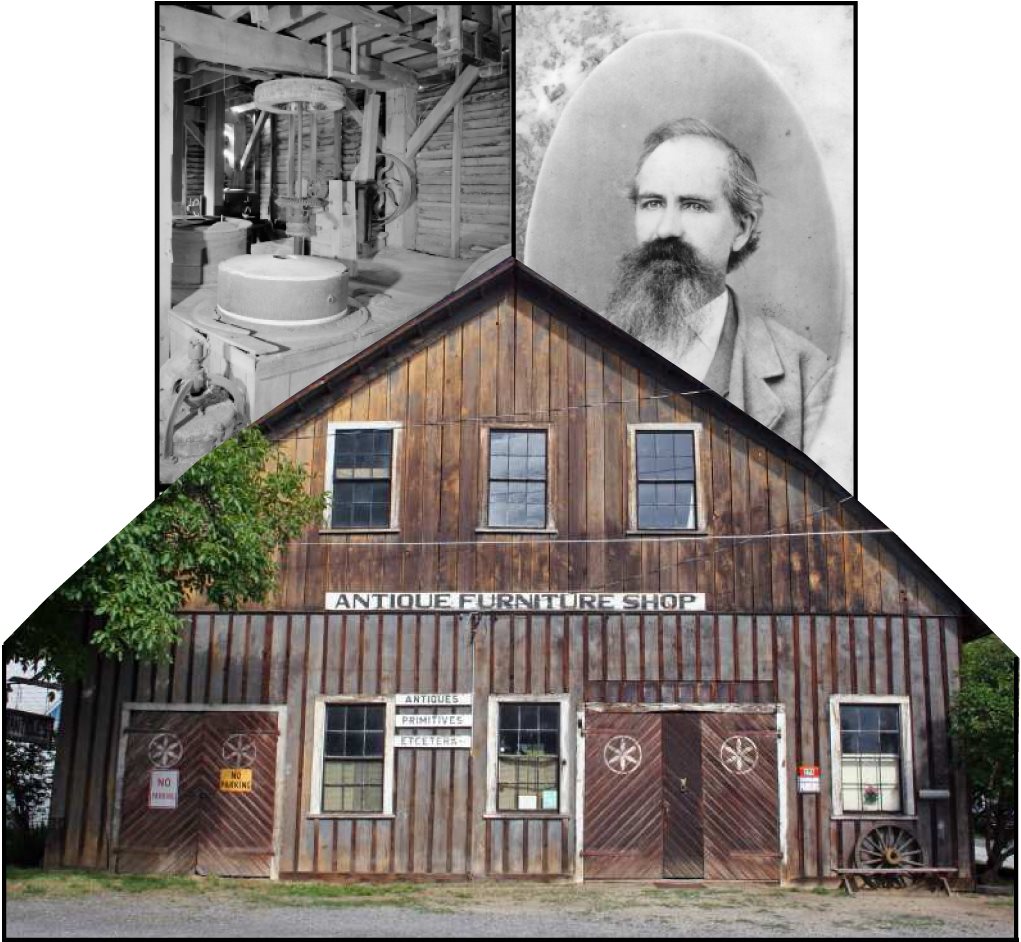

The Applebaker Barn, located at the corner of North 3rd and D streets, is one of the few remaining structures directly linked to Jacksonville’s early agricultural economy. The building was originally a steam grist mill, located in the 800 block of South 3rd Street. Constructed in 1880 at an estimated cost of $11,000, it was described in that December’s Democratic Times newspaper as 3 stories in height with a solid stone foundation. It boasted the “latest most improved machinery” that could grind the “finest quality flour” at the rate of 1,100 pounds of wheat an hour or 150,000 bushels a year—equivalent to all the surplus wheat grown in the Rogue Valley at that time. Businessman Gustav Karewski purchased it in 1881 and within three years it ranked third in the state in flour production. In 1915, Joseph Applebaker dismantled, moved, and reconstructed the reconfigured building at its present location to serve as his blacksmith’s shop.

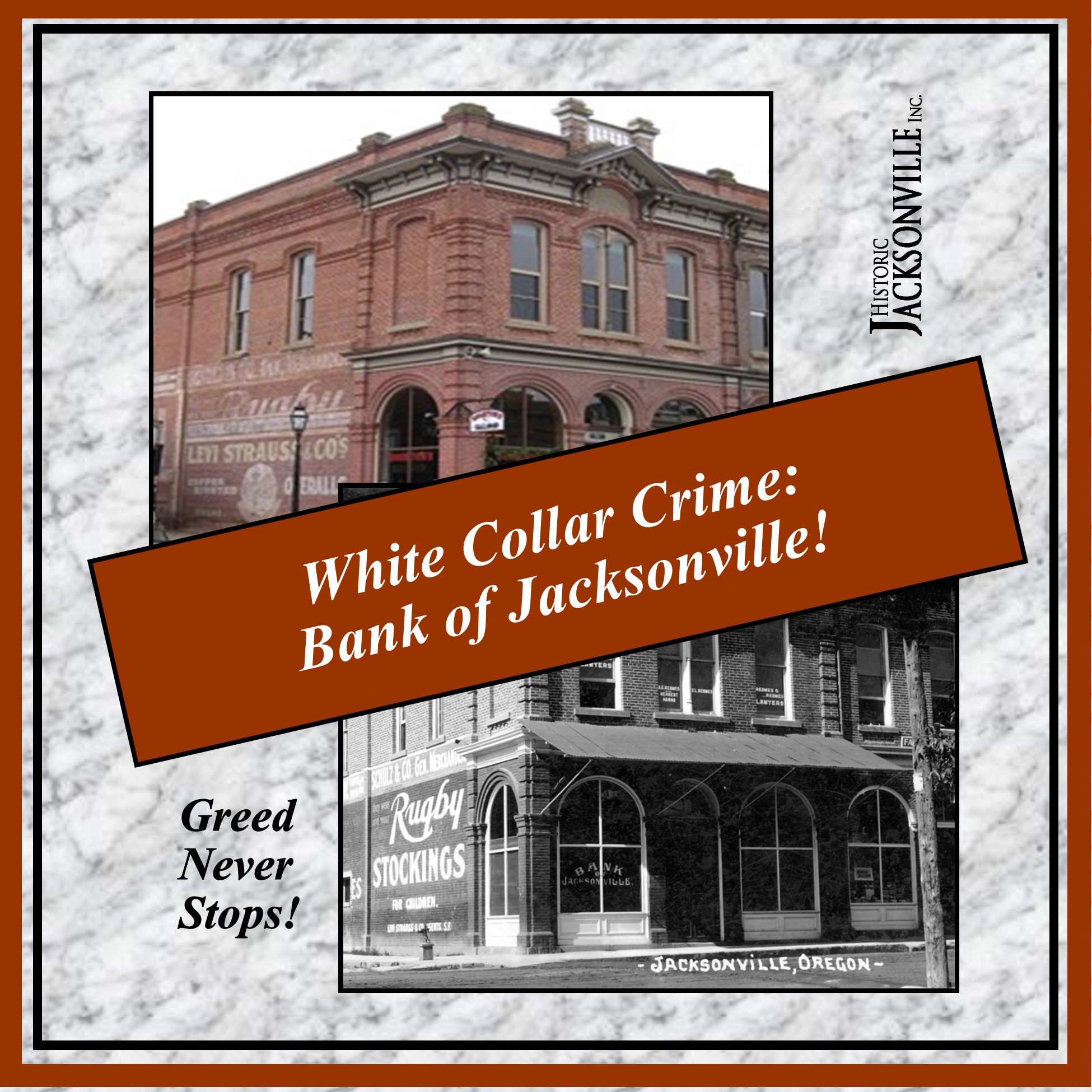

Bank of Jacksonville

One of the reasons Cornelius Beekman closed his bank in 1912 was the 1907 opening of the Bank of Jacksonville on the ground floor of Red Men’s Hall across California Street at the corner of South 3rd. However, it turns out that the Bank of Jacksonville was not exactly on the “up and up”!

In August of 1920, its President, W.H. Johnson, was arrested and indicted on 30 felony counts including misstatement of the bank’s condition, receiving monies in a known insolvent banking institution, false certification of checks, and making false statements to a bank examiner. The President of the Bank of Jacksonville became one of the more distinguished “guests” of the Jackson County jail.

Johnson was not only bank President and cashier, he was also City Treasurer and deacon and treasurer of the Jacksonville Presbyterian Church. Johnson was convicted and spent 10 years in the state penitentiary. Dozens of prominent citizens were eventually charged with aiding and abetting the defrauding of the bank—including the Jackson County Treasurer.

Depositors were both shocked and panicked—bank monies were not insured! In 1930, when the investigation was finally closed and the remaining bank assets liquidated, depositors received at best 17 cents on the dollar. Most lost their life savings; the County lost $107,000.

While Cornelius Beekman’s late 19th Century banking practices may not have been exactly orthodox, they were both ethical and community oriented. Learn more about them in Historic Jacksonville’s Beekman Bank “Behind the Counter” tours every weekend this summer.

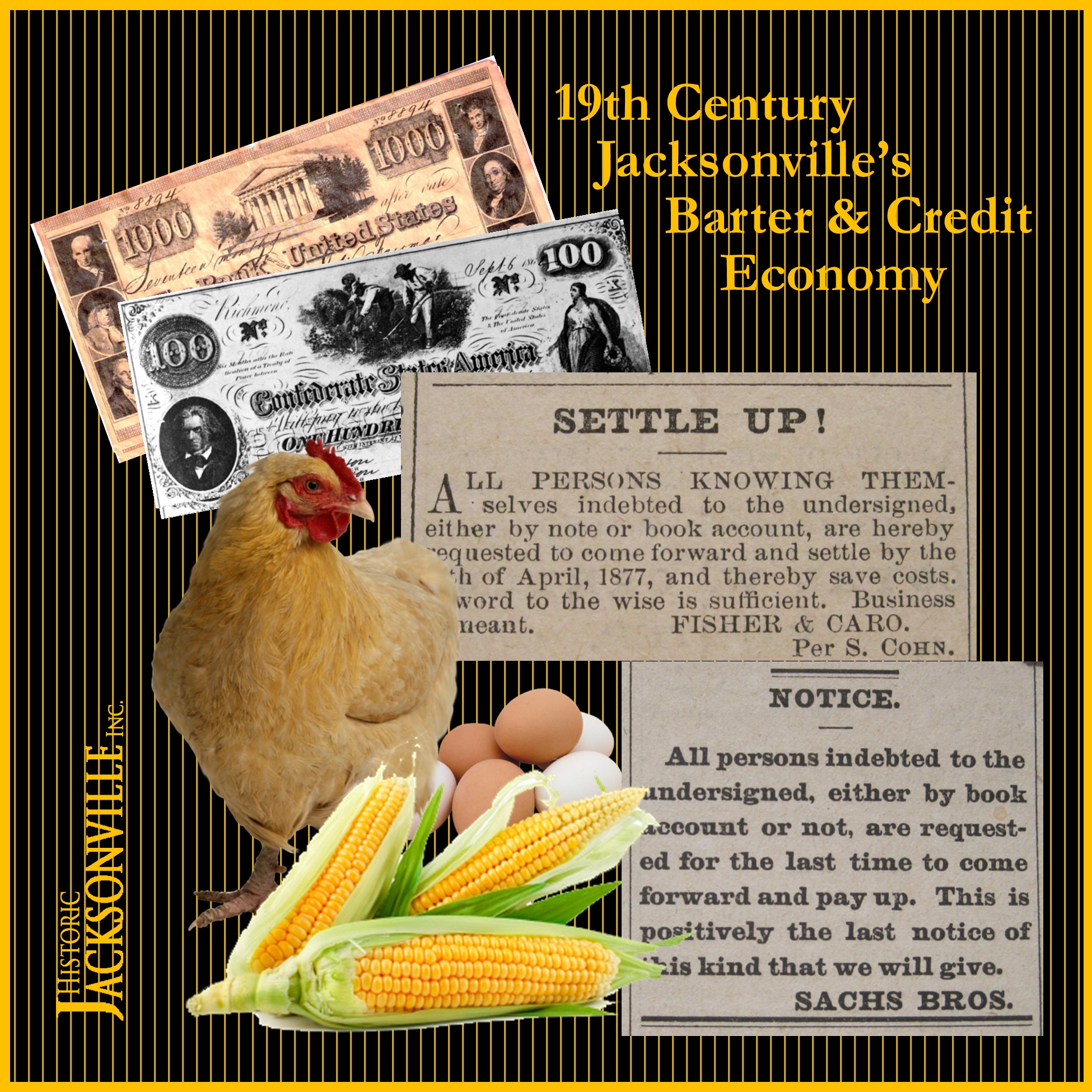

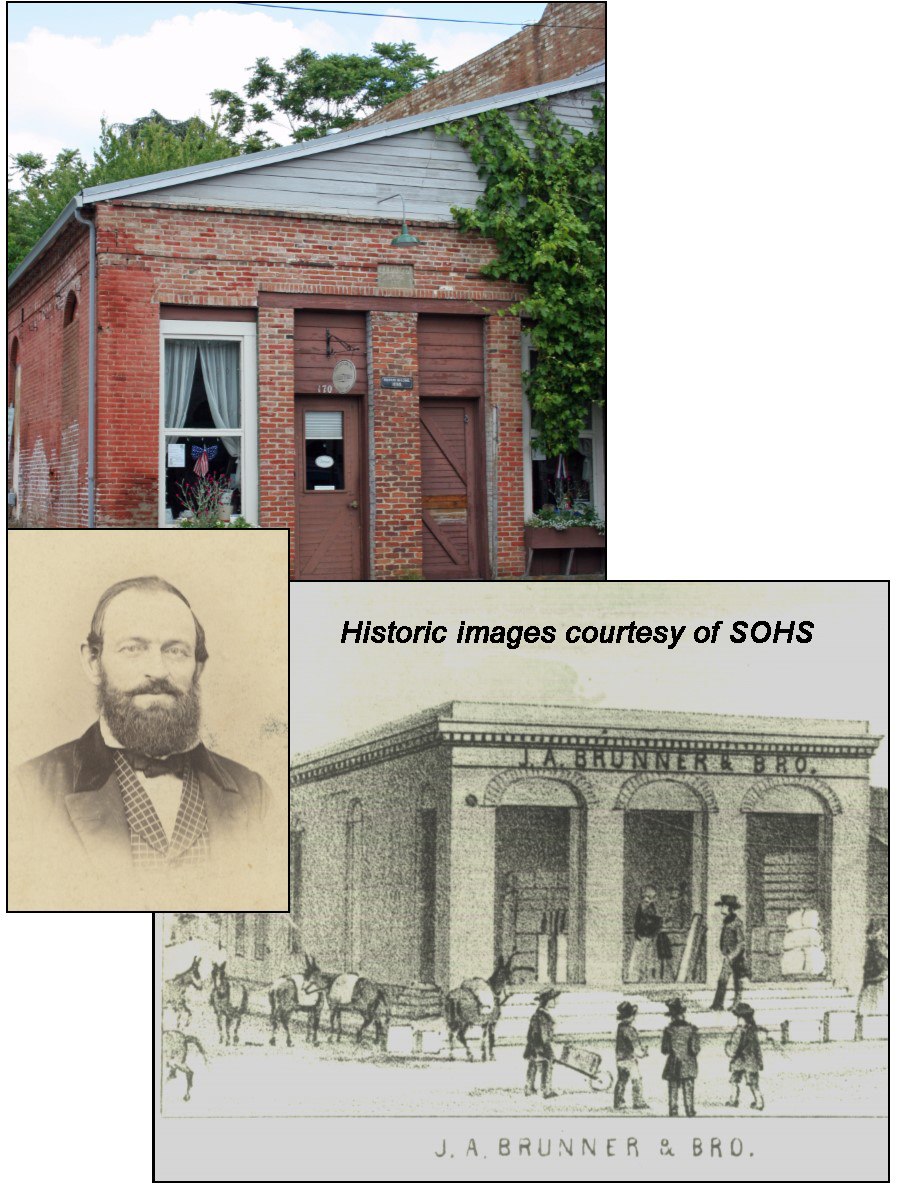

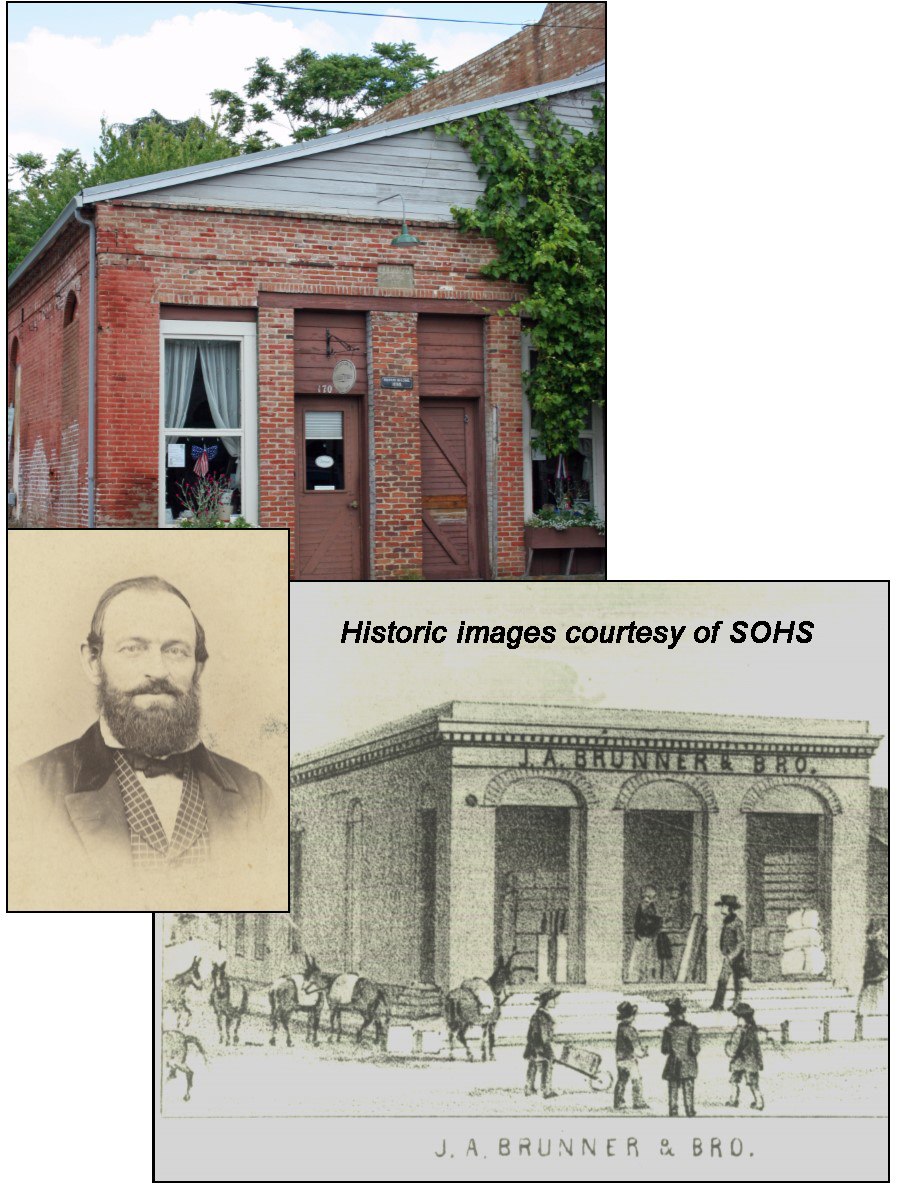

Barter and Credit Economy

In mid-1800s Jacksonville, multiple currencies were in circulation and the value of most was unknown. Gold and Mexican silver were the most trusted. But miners and farmers seldom had those readily at hand. Until the crops were harvested or the mine paid off, individuals and families relied on trade and credit to obtain needed services and supplies. But the merchants still had to pay their suppliers in order to bring in fresh merchandise.

Before each buying trip to San Francisco, or on the verge of arrival of new goods, each merchant would take out and ad in the newspaper calling in the debts owed him. The first published ad that still exists was taken out in the January 5th issue of the Table Rock Sentinel by J.A. Brunner & Bro. It read: “Notice! Is hereby given that accounts due to our firm must be settled by the 31st of this month, otherwise they will be placed in the hands of the sheriff for collection.”

Lawsuits were common whenever a merchant had difficulty collecting money owed him. Gustav Karewski may have set the record filing 32 lawsuits between 1873 and 1882. Lawsuits were also common when the wholesaler who had supplied the merchant’s good were not paid. Some merchants deliberately collected as much merchandise as they could on credit and then left the area and disappeared with as much of their merchandise as possible.

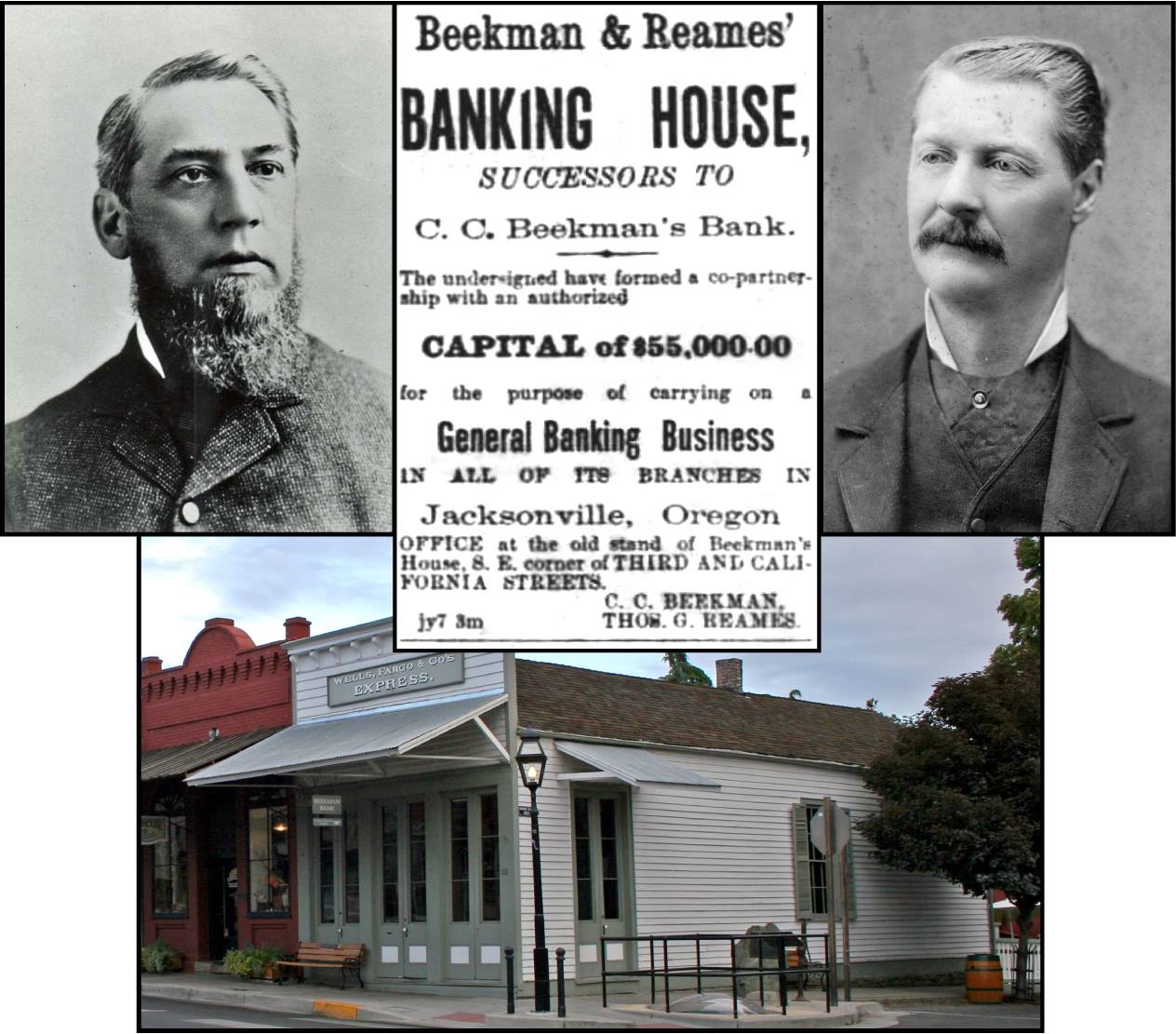

Beekman & Reames Banking House

In 1887 Thomas Reames joined his California Street neighbor Cornelius Beekman as a co-partner in the C.C. Beekman Bank, creating Beekman & Reames Banking House at the corner of California and North 3rd streets in Jacksonville. In addition to general banking, Beekman & Reames invested heavily in county warrants and large land holdings. The partnership continued until Reames’ death in 1900 from complications from a cold. However, Beekman continued to use the Beekman & Reames imprint for some years afterwards—after all, why waste perfectly good stationery and business cards….

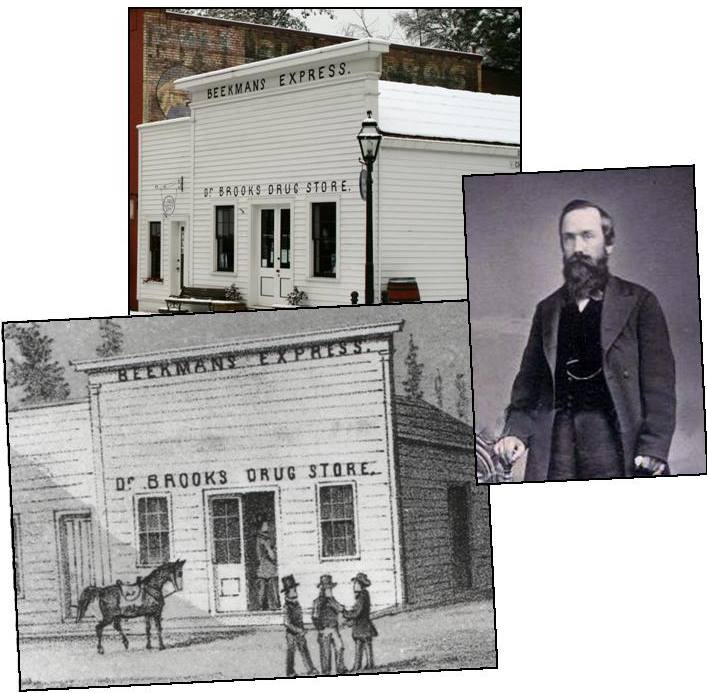

Beekman Express Office

When Cornelius Beekman opened his express office in at the corner of Californis and S. 3rd streets in 1856, he shared the space with Dr. Charles B. Brooks’ drugstore. The present building on that site is a 2003 faithful reproduction of the original. A 17-year-old Brooks had graduated from Centre College in Danville, Kentucky with a degree in “necrology”; continued his study of medicine in Louisville; and then lured by the promise of the West, joined a wagon train of settlers heading for Southern Oregon, arriving in Jacksonville in 1853. For the first 2 years he practiced medicine and ran a hospital at the corner of 3rd and D streets, “back of Union House.” When Beekman opened his Express Office in 1856, Brooks joined him, adding “drugs, medicines, perfumeries, oils, etc.” to his offerings. The partnership had ended by the time Beekman constructed the current Beekman Bank in 1863 since 1864 ads show that Brooks had moved his practice to the Dalles. He subsequently became Wasco County Coroner, married, and then died of pneumonia in 1875 at age 43.

Beekman’s Bank

Cornelius C. Beekman erected his second bank building in 1863 at the corner of California and North 3rd streets in Jacksonville. Begun as a gold dust office in 1856, Beekman saw over $40 million in gold cross his counters during Jacksonville’s heyday in the 1800s—equivalent to over $1 billion in today’s currency! Beekman’s Bank is the oldest financial institution in the Pacific Northwest and remains furnished exactly as it was when Beekman closed and locked the doors for the last time in 1915. Explore the “Secrets & Mysteries of the Beekman Bank” during 45-minute candlelight tours beginning at 6, 7, and 8 p.m. on April 5 and 6. Admission, $5. Reservations required!

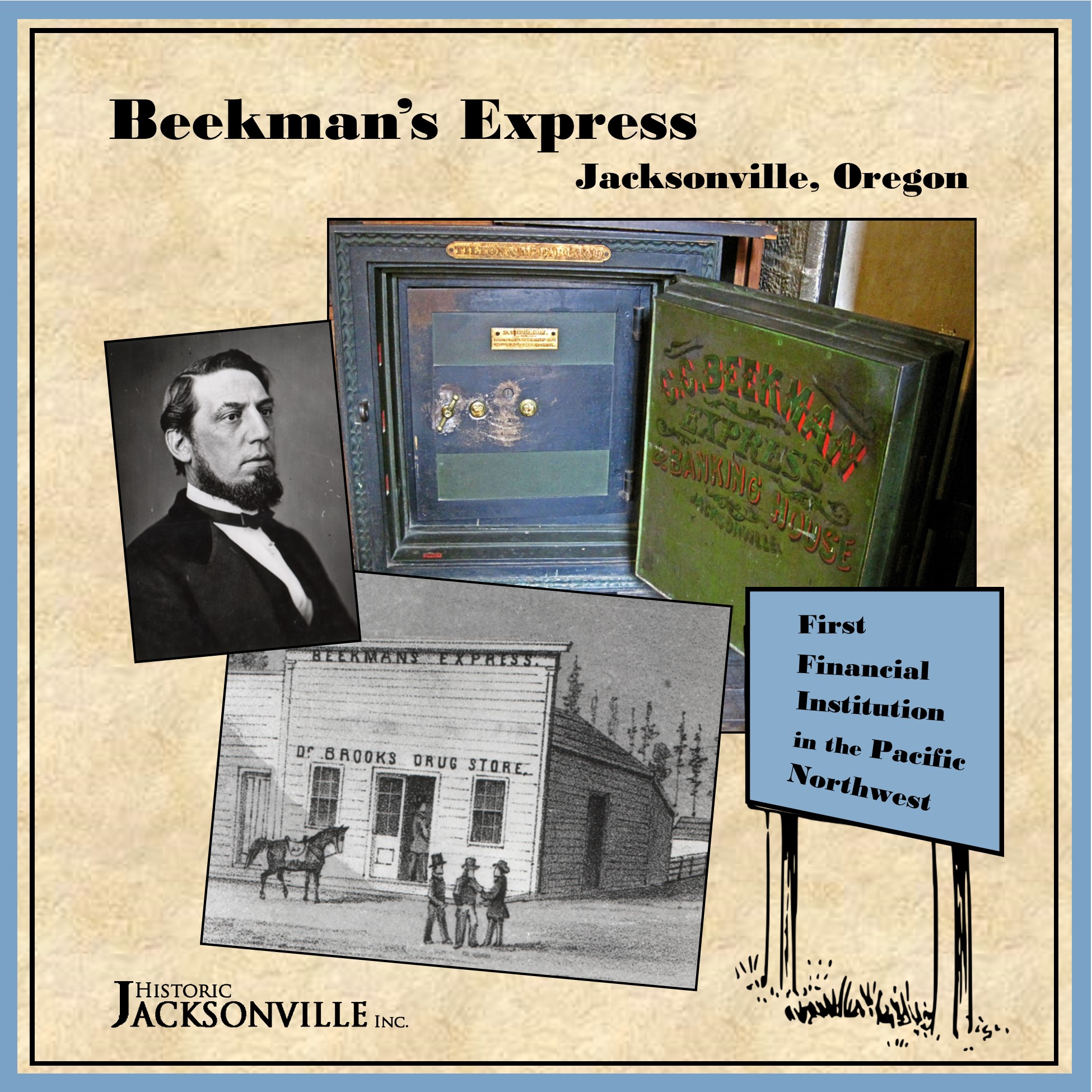

Beekman’s Safe

Did you know that Jacksonville boasted the first financial institution in the Pacific Northwest? Of course, it didn’t look like much. It was just a large safe!

Cornelius Beekman had come to Jacksonville in 1853 as an “express” rider for Cram Rogers & Co., carrying the mail, newspapers, parcels, gold, and even passengers 2 to 3 times a week roundtrip between Jacksonville and Yreka. Express was the early version of postal service, UPS and Fed Ex. When Cram Rogers went belly up in 1856, Beekman opened his own express company.

Jacksonville was a gold mining town, and Yreka was the connecting stage point for San Francisco and the mint, so Beekman carried a lot of gold. Shortly after opening his own express company, Beekman bought a large safe to store the miner’s gold for either shipment or safe keeping. And with that safe, he established the first financial institution in the Pacific Northwest. You can still see that safe in the Beekman Bank Museum, the banking office Beekman built in 1863 at the corner of North 3rd and California streets. And perhaps we should mention that in Jacksonville’s heyday, the Beekman “Bank” saw over $40 million in gold cross its counters—worth over $1 billion today!

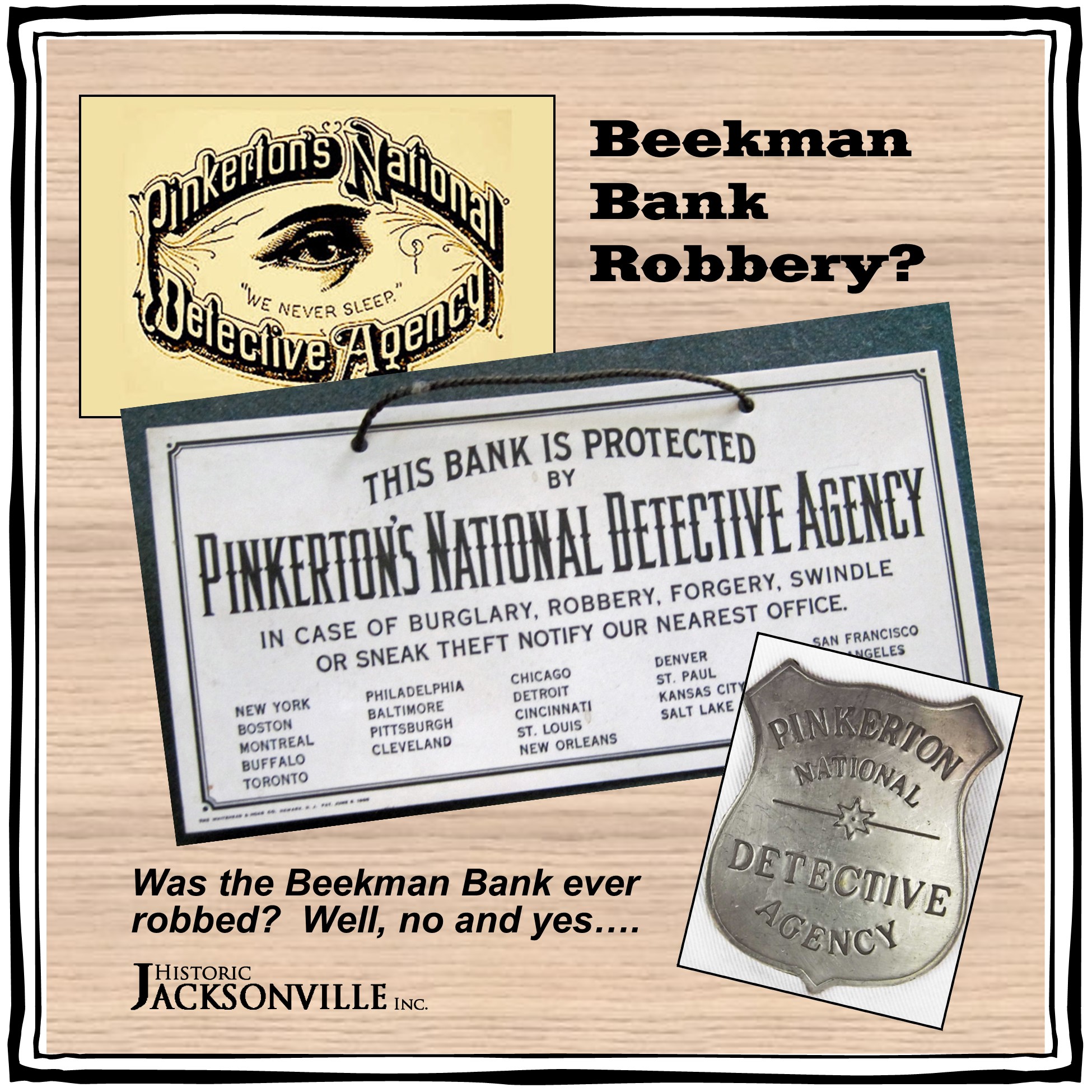

Beekman Bank Robbery

Regarding the C.C. Beekman Bank, Jacksonville’s original Wells Fargo agency and the oldest financial institution in the Pacific Northwest, one of the questions docents are frequently asked is “Was the bank ever robbed?” It turns out there’s a “yes” and “no” answer!

In December 1938, long after the bank had been closed and declared a museum, some guns were stolen. No other losses were reported.

However, there was a “yeggman’s plot to rob the Bank in 1913 that was thwarted by the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the local sheriff.” According to the March 17, 1913, Ashland Tidings¸ “Because of its isolation and the lack of police protection it was viewed by the yeggs as ‘soft.’” The Pinkertons had received a “inside” tip to this effect and arranged for men to guard the building and watch incoming trains. As a precautionary move, much of the money in the safes along with valuable papers were shipped elsewhere. After local residents became curious as to why armed men were wandering around the building at night, the sheriff’s office admitted there was a plot to rob the Bank. Once the robbers’ plans became public, the attempt was never made.

Don’t miss your chance to “Step Behind the Counter” of the Beekman Bank this weekend! Museum “banking hours” are 11am to 3pm. You can take a self-guided tour of the or interact with a costumed docent who will gladly share as little or as much information as you might like about 19th century banking practices and Beekman’s personal way of doing business.

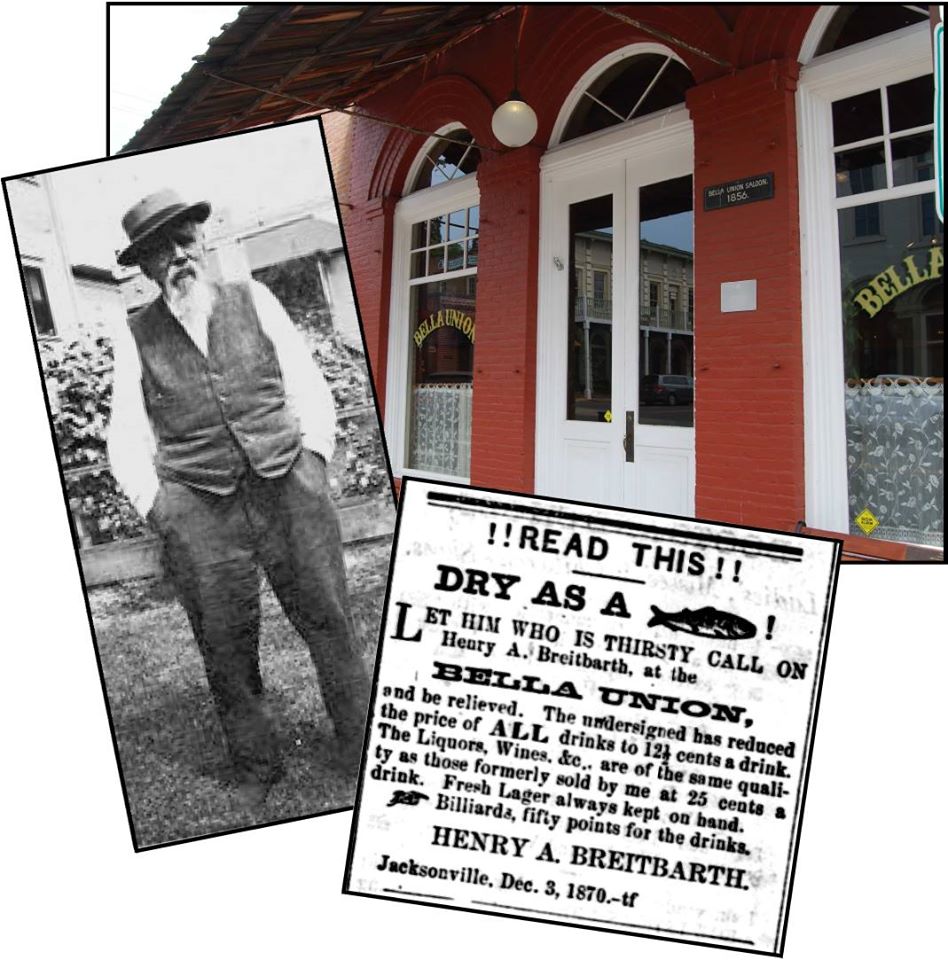

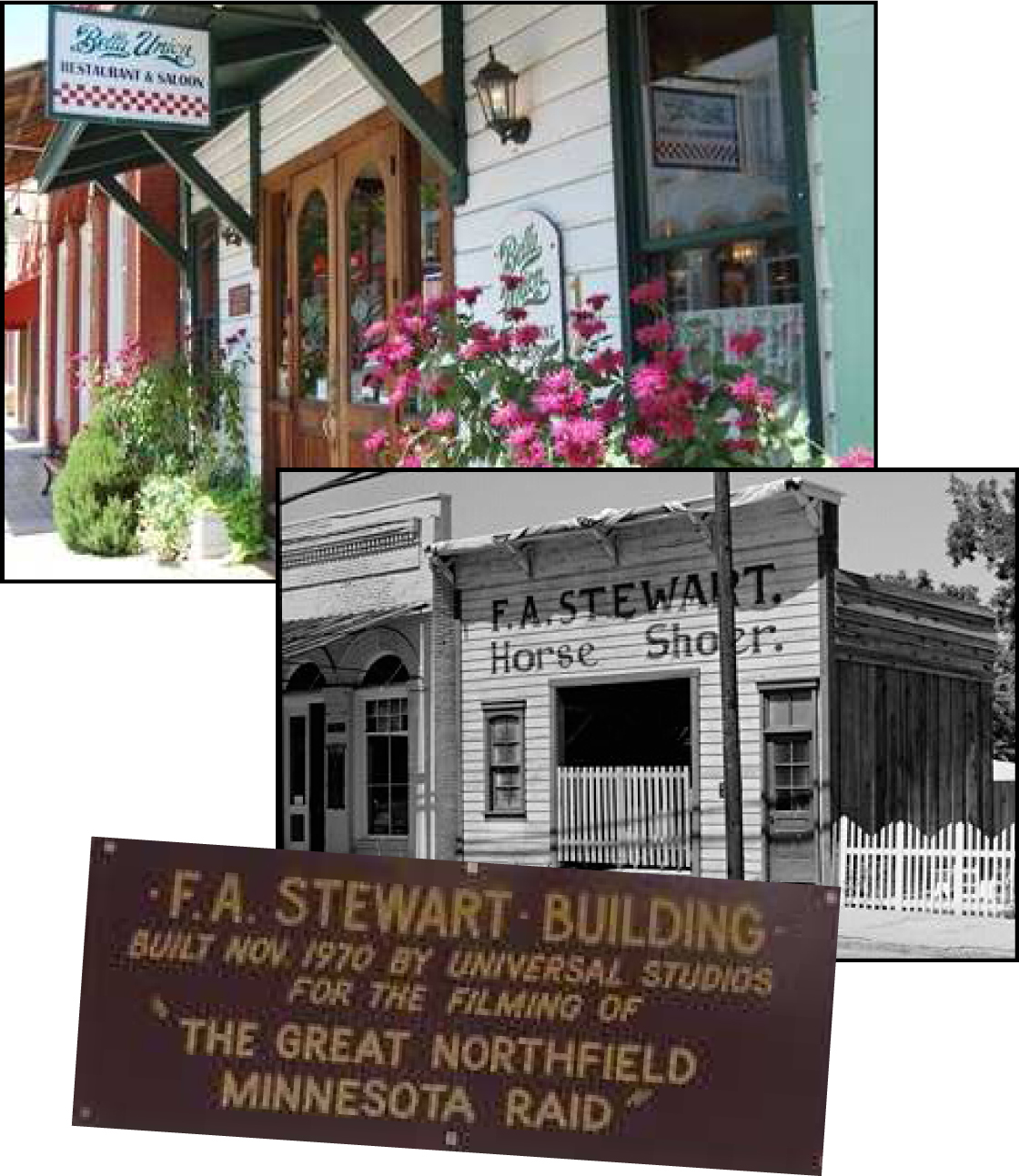

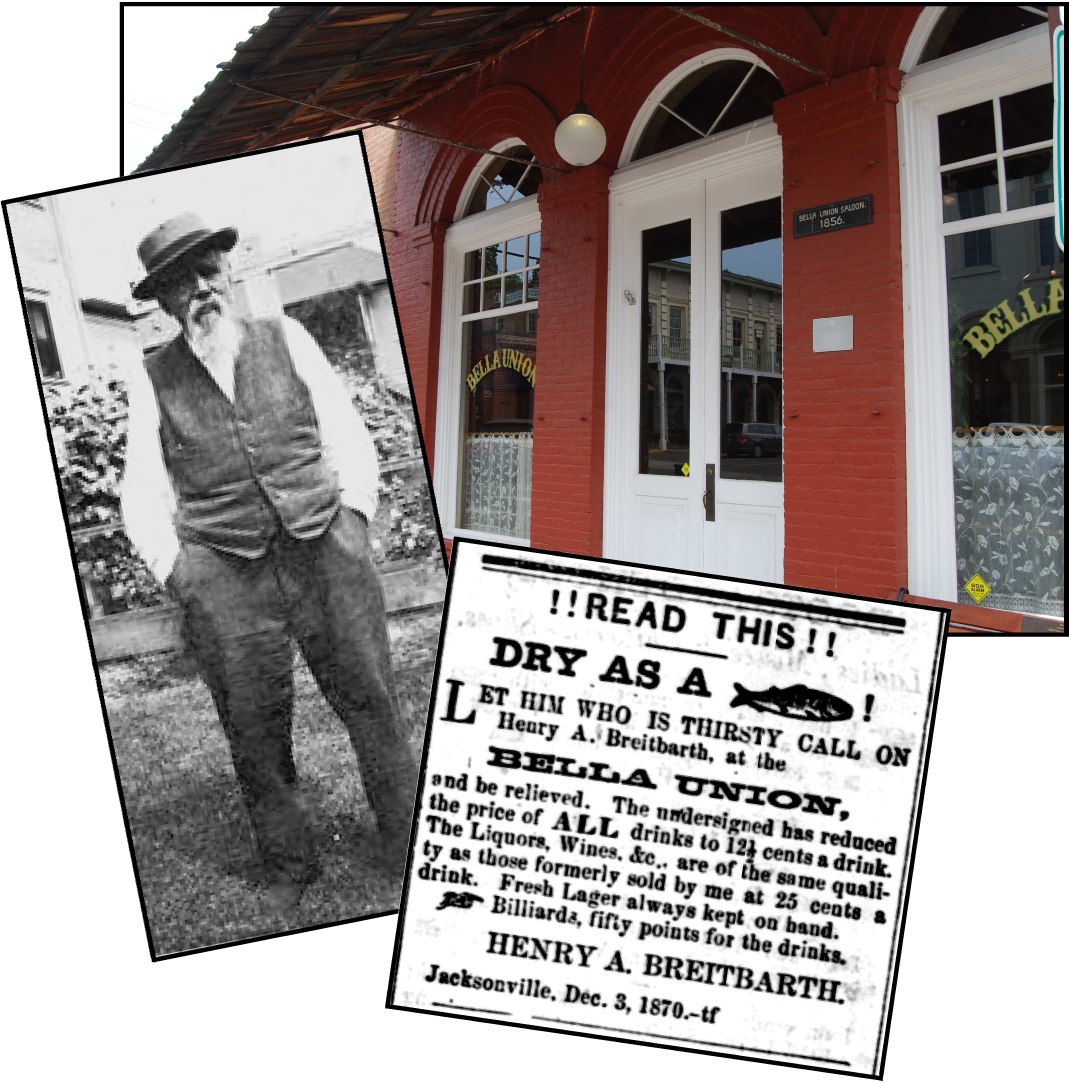

Bella Union #1

The oldest part of the Bella Union Restaurant and Saloon at 170 W. California Street was constructed in 1874 by pioneer woodworker and builder David Linn after the fire of 1874 destroyed many of the original buildings in Jacksonville. Linn had purchased the lot in 1856 and erected a one-story brick building to house his woodworking shop. After Linn relocated his business to the corner of California and Oregon, he rented the space to a series of tenants, including Prussian native Henry Breitbarth. Breitbarth operated the original Bella Union Saloon at this location from 1864 to 1871. It was one of 7 saloons in early Jacksonville and offered its customers billiards and liquors.

Bella Union #2

The Bella Union Restaurant and Saloon at 170 W. California Street is not one building, but three. The old brick portion, constructed in 1874, replaced an earlier building that housed the original Bella Union Saloon. The middle portion and main entry is straight out of Hollywood. It was built in 1970 when Jacksonville became the movie set for The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid starring Cliff Robertson as Cole Younger and Robert Duvall as Jesse James. The film is based on the James-Younger Gang’s most infamous escapade—the September 7, 1876, robbery of “the biggest bank west of the Mississippi.”

Blue Door Garden Store

The building that is now the Blue Door Garden Store at 130 West California Street in Jacksonville was built around 1862 by German-born John Neuber to house his jewelry store. Neuber was Jacksonville’s first goldsmith and silversmith. He specialized in solid gold buckles for women’s belts. While running to fight one of the periodic fires that broke out in the town’s early wooden structures, Neuber incurred severe head injuries. In 1874 he was declared insane by the Jackson County commissioners and ordered to the state insane asylum where he died a year later.

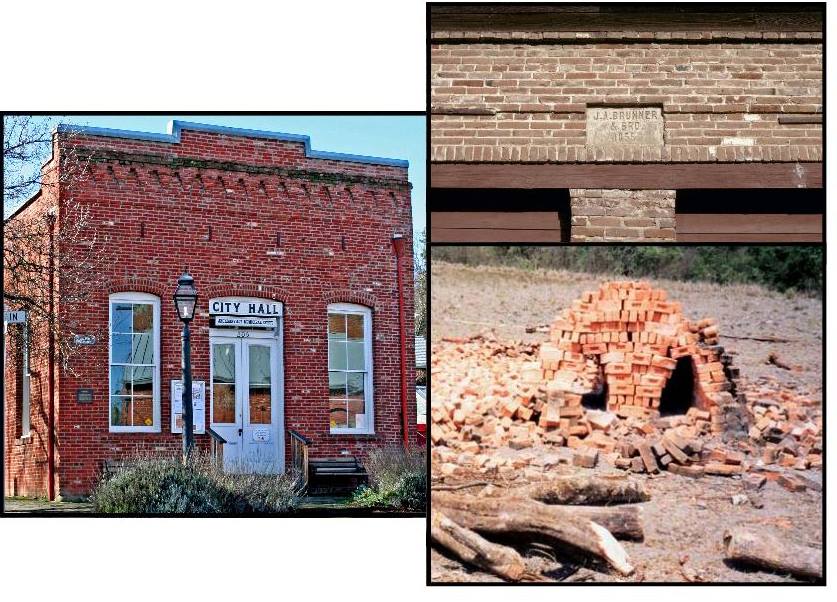

Brick Buildings

Look closely at Jacksonville’s historic brick commercial buildings. Most are second generation structures constructed in the late 1800s after fires wiped out the original wooden buildings. The bricks used in these buildings were fired locally, often on site. They would be stacked into an igloo shape, forming their own kiln, with holes left for the firewood. While convenient, this firing method produced inconsistent results—the middle bricks would be good, but the bricks closest to the fire would be blackish brown and overdone. The bricks on the outside would be peachy pink and underfired. Over and underfired bricks are porous, allowing water to seep through, so most of the Jacksonville brick buildings were originally painted to seal them from the elements.

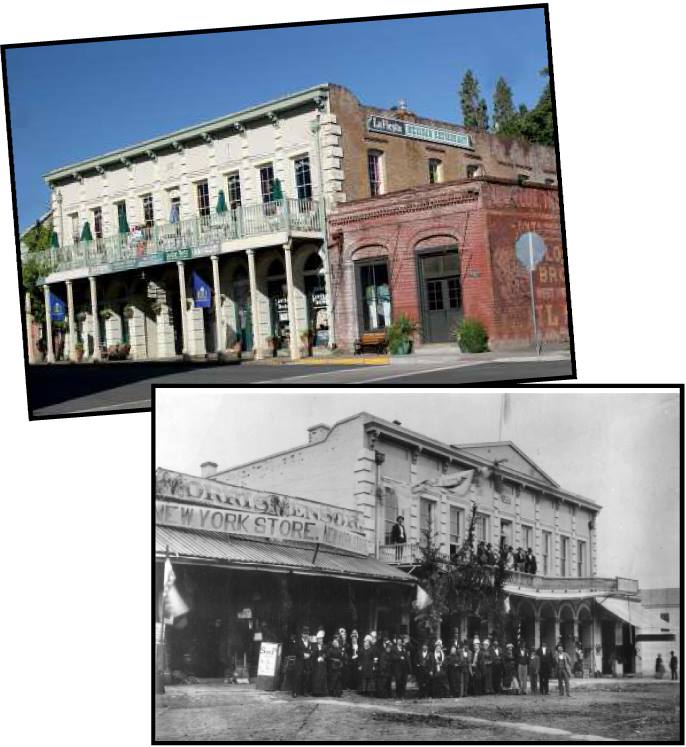

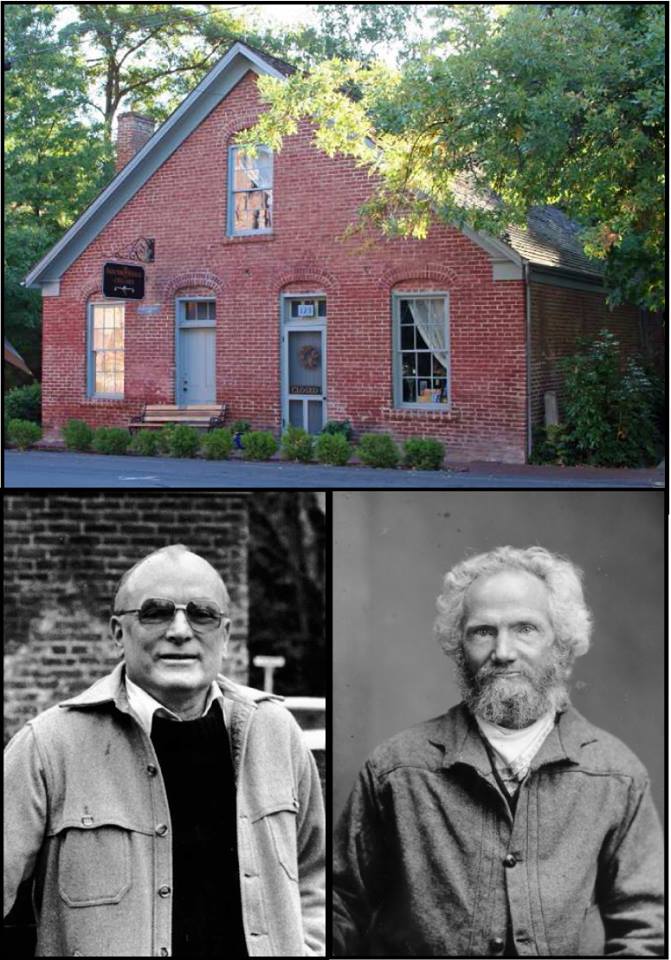

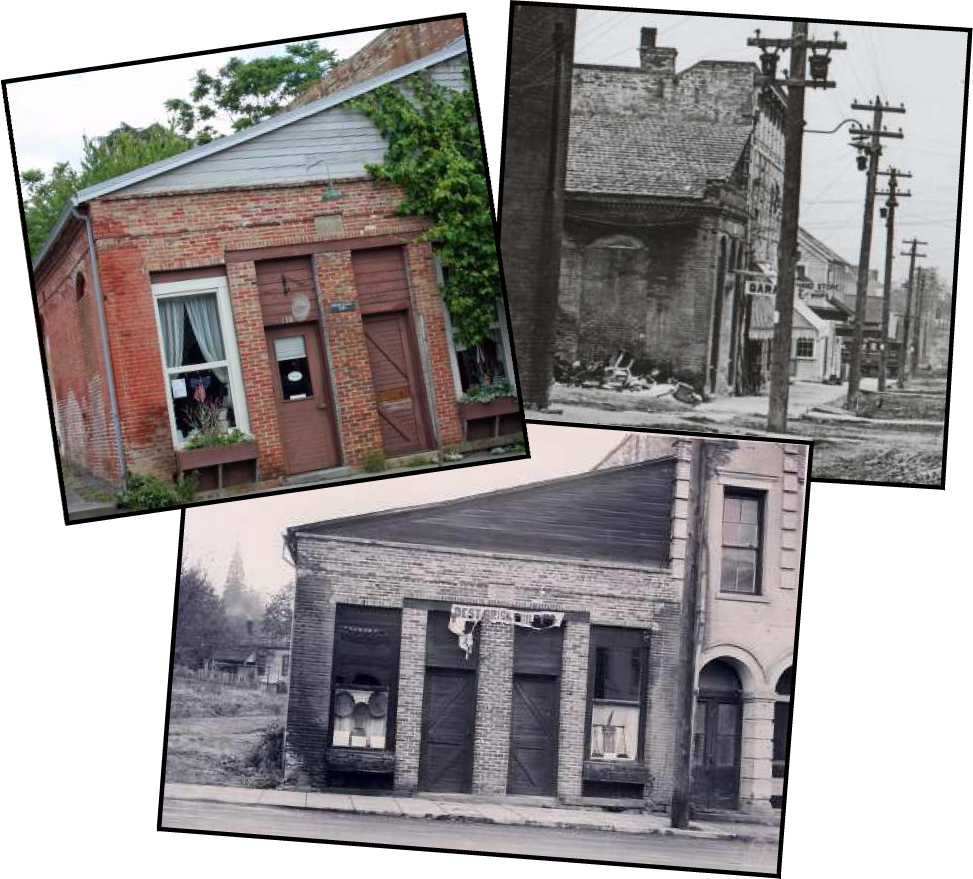

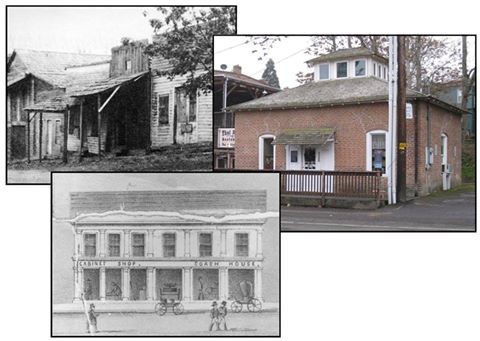

Brunner Building #1

Constructed around 1855, the Brunner Building at 170 S. Oregon Street was the second brick building erected in Jacksonville and remains the town’s and Oregon’s oldest brick building still standing. Jacob Brunner was an early arrival to the young gold mining camp and by 1854 had established himself as a merchant carrying one of the heaviest stock of goods. A year earlier, Brunner had purchased the Main and Oregon corner lot at the new settlement’s first commercial street intersection. By January 1856 he was advertising his “fire-proof brick” store. An 1860 rear addition made it not only the “largest store building in Jackson County” but also “the largest south of Salem.” Brunner was among the first elected Trustees of Jacksonville after the town government was organized in 1860. However, by 1863 he had sold the “Brunner Building.” Belatedly catching “gold fever,” he appears to have moved on to the mines of southern Idaho.

Brunner Building #2

Last week Historic Jacksonville, Inc. shared the fact that Old City Hall stands on the site and is built from bricks from the first brick building constructed in Jacksonville—the 1854 Maury & Davis store. Directly across W. Main is the second brick building erected in town, the 1855 Brunner building. Although it has undergone numerous modifications over the years, it remains the town’s and Oregon’s oldest brick building still standing. Jacob Brunner was an early arrival to the young gold mining camp and by 1854 had established himself as a merchant carrying one of the heaviest stock of goods. A year earlier, Brunner had purchased the Main and Oregon corner lot at the new settlement’s first commercial street intersection. By January 1856 he was advertising his “fire-proof brick” store. An 1860 rear addition made it not only the “largest store building in Jackson County” but also “the largest south of Salem.” Brunner was among the first elected Trustees of Jacksonville after the town government was organized in 1860. However, by 1863 he had sold the “Brunner Building.” Belatedly catching “gold fever,” he appears to have moved on to the mines of southern Idaho.

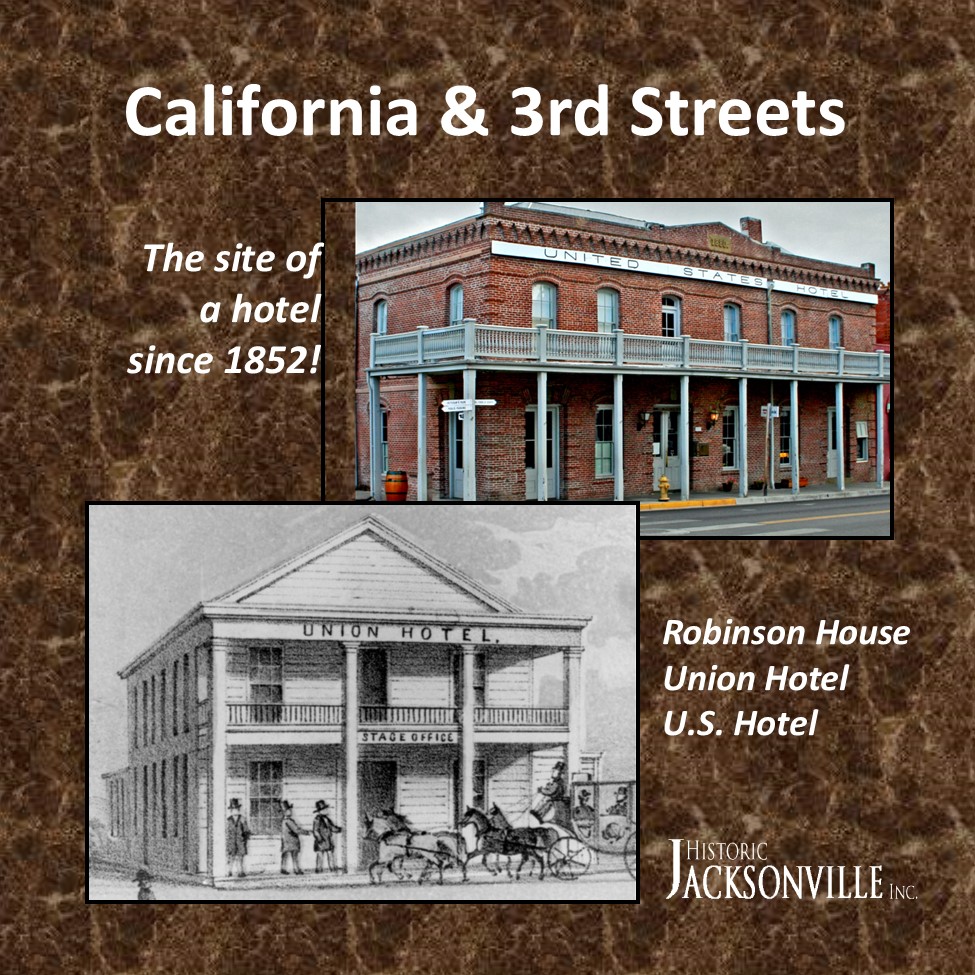

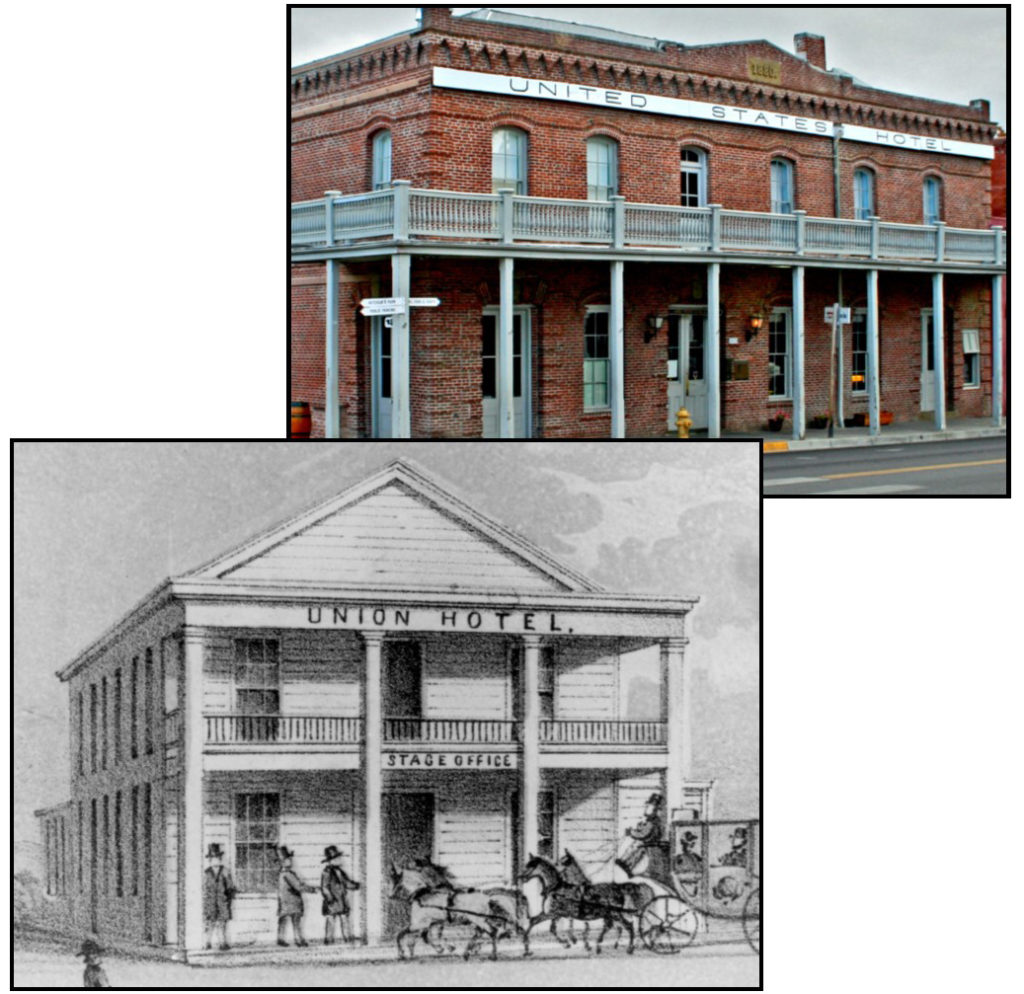

California & 3rd Street Hotels

The southeast corner of Oregon and California streets has been the site of a hotel almost since Jacksonville was founded. As early as November 1852, Jesse Robinson claimed “squatters rights” to an existing 2-story wood frame structure. The “Robinson House” became a “private boarding house patronized by the elite.” Austin Badger and Nelson Smith purchased the building in late 1855, renamed it the Union Hotel, and enlarged it.

When Badger and Nelson couldn’t pay their debts, the Union Hotel was sold to Louis Horne who rechristened it the U.S. Hotel. Horne “improved” the hotel in 1868 by adding a 50’ x 30’ hall fronting on E. California. The 2nd floor, resting on “steel springs,” was made expressly for dancing; the ground floor housed offices and shops. Three years later a skating rink was opened in “Horne’s Hall.”

The disastrous 1873 fire which leveled many of the wood frame structures on California Street was believed to have originated in a flue of the U.S. Hotel. The fire destroyed everything on the block…except for Horne’s chicken coop. The property was subsequently sold at a sheriff’s sale and then resold to brick mason George Holt, and his wife, hotel proprietress Jeanne DeRoboam Holt. George fired the bricks for his wife’s long dreamed-of, brick hotel. The brick U.S. Hotel, the structure we know today, opened in 1880 with a Tammany Day celebration, a Fourth of July Ball, and a visit by President Rutherford B. Hayes.

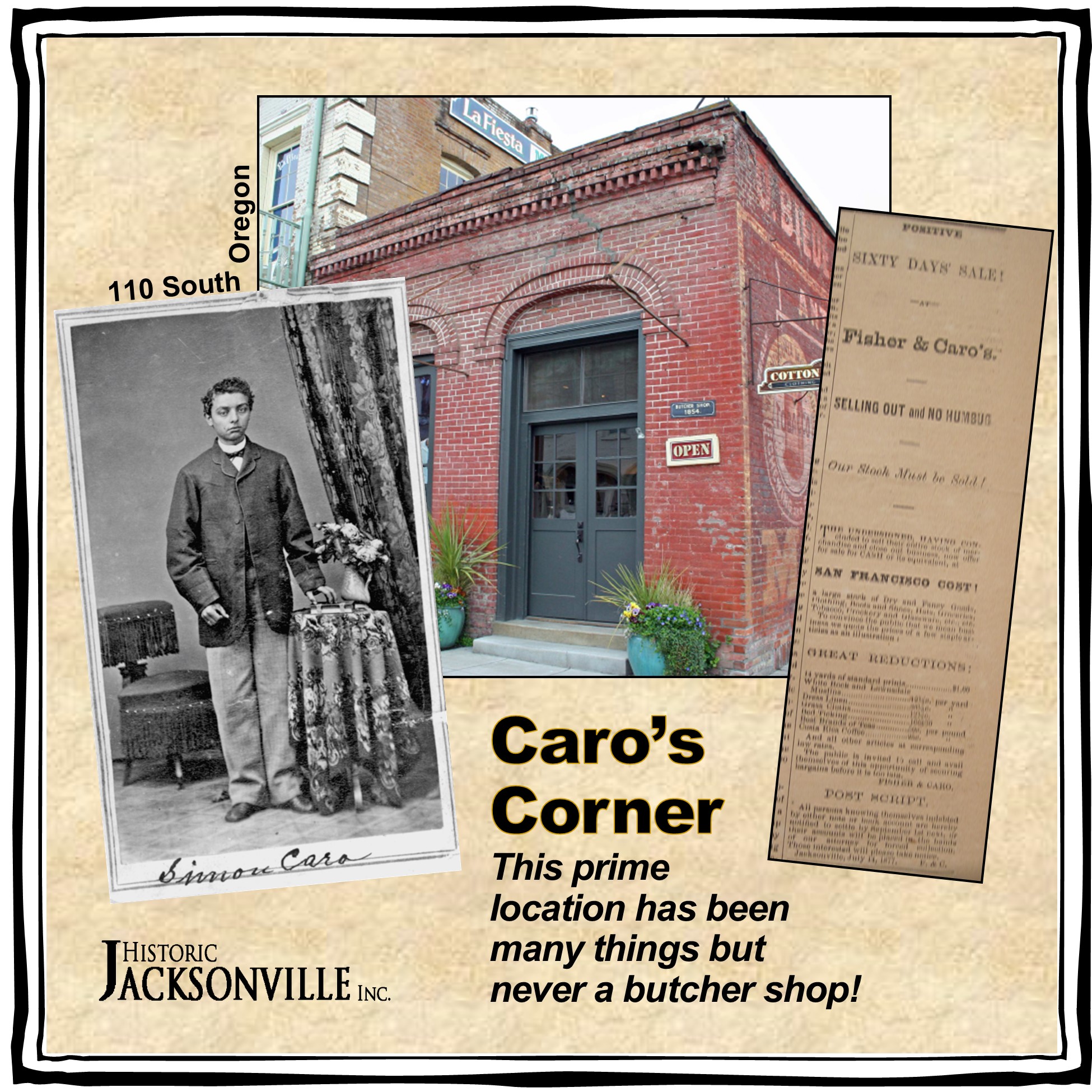

Caro’s Corner

Although this 1-story brick building was constructed in 1861 for the Haines brothers, for many years this prime Oregon and California street intersection was known as Caro’s Corner. By 1866 Isador Caro was conducting a general merchandise variety store at this site. That same year, he was joined by his 16-year-old brother, Simon, who arrived in Jacksonville directly from Hamburg, Germany. While in Jacksonville, Simon learned Chinese to more readily deal with the 800 Chinese miners in Jackson County. Even when the brothers moved to Ashland in 1870, becoming among the first merchants in that city, the intersection retained its Caro’s Corner moniker. And Simon did retain local business interests, entering into partnership with the Fisher brothers. Simon apparently had a real knack for business since the 1870 census showed a 20-year-old Simon as having $500 in real estate and $3,000 in his personal estate and subsequent censuses showed him as head of household. In fact, Simon was such a success that he was able to visit his mother in Germany every other year until her death.

Chinatown

Jacksonville was home to the first Chinatown in Oregon, located along West Main in the area where Gogi’s, Elan Guest Suites, and Veterans Park are now to be found. This area was the town’s original commercial center, but as businesses relocated to California Street in the 1850s, this block became home to hundreds of Chinese workers brought here by labor bosses to work the gold mines. As the gold played out, the Chinese Quarter was gradually abandoned. In 1888, most of what were by then derelict buildings burned in one of Jacksonville’s many fires.!

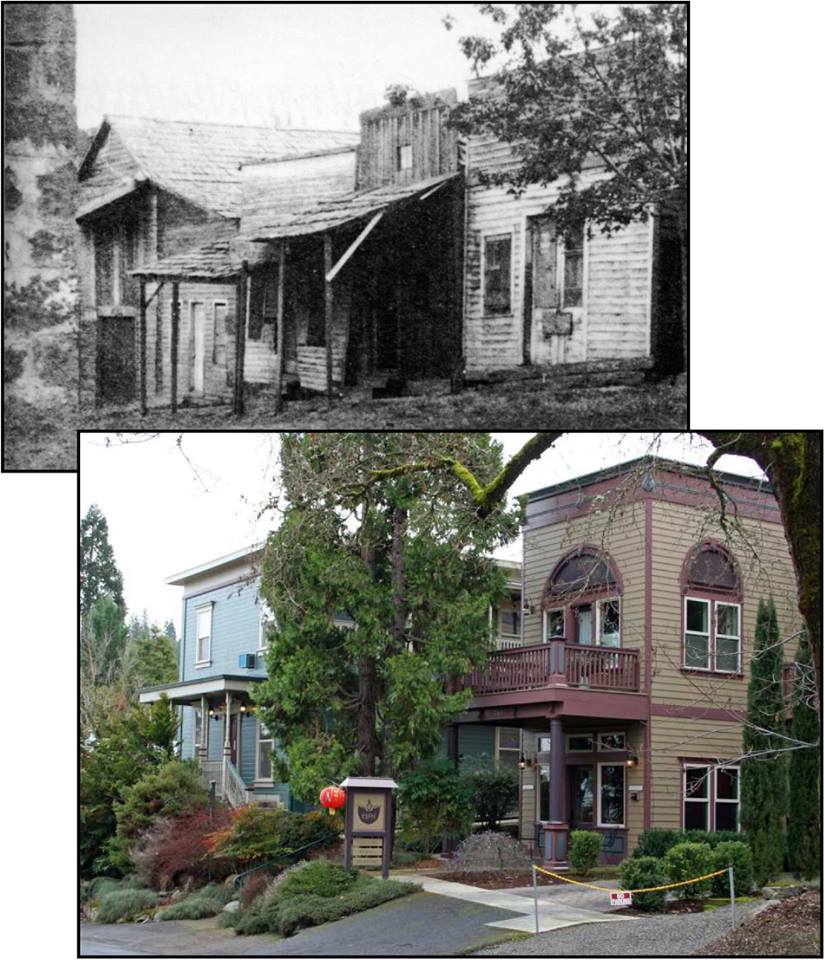

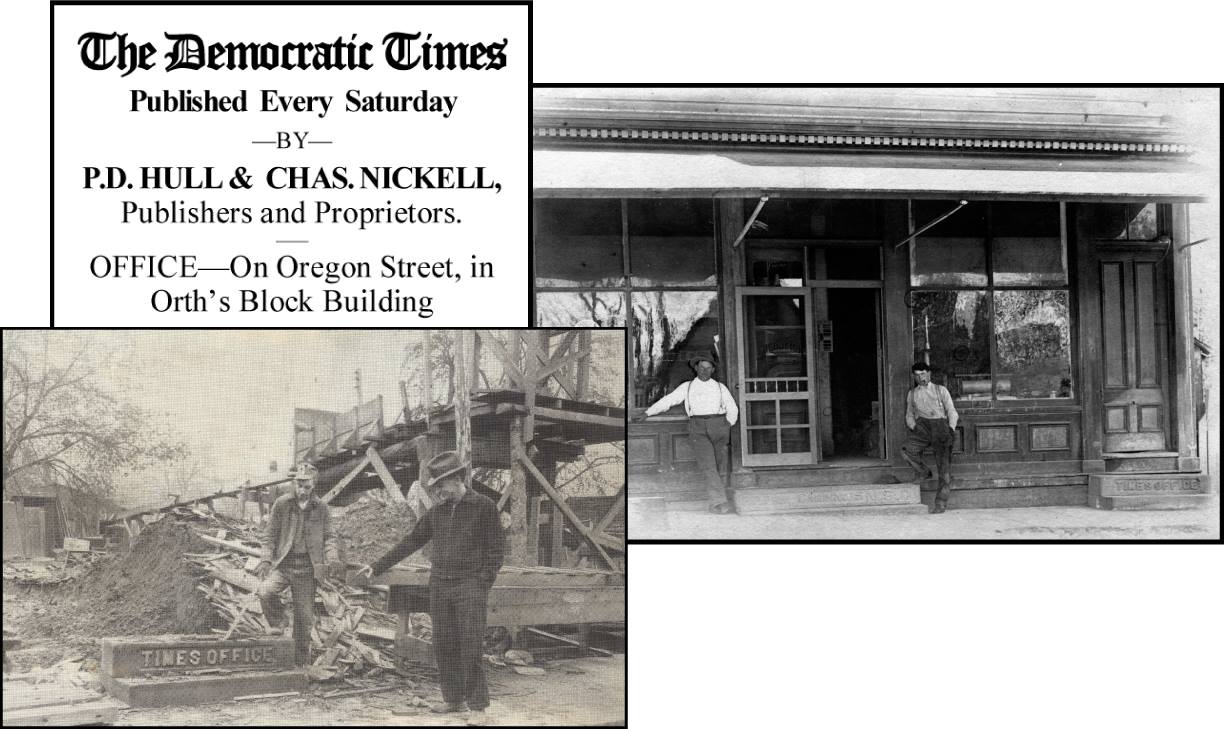

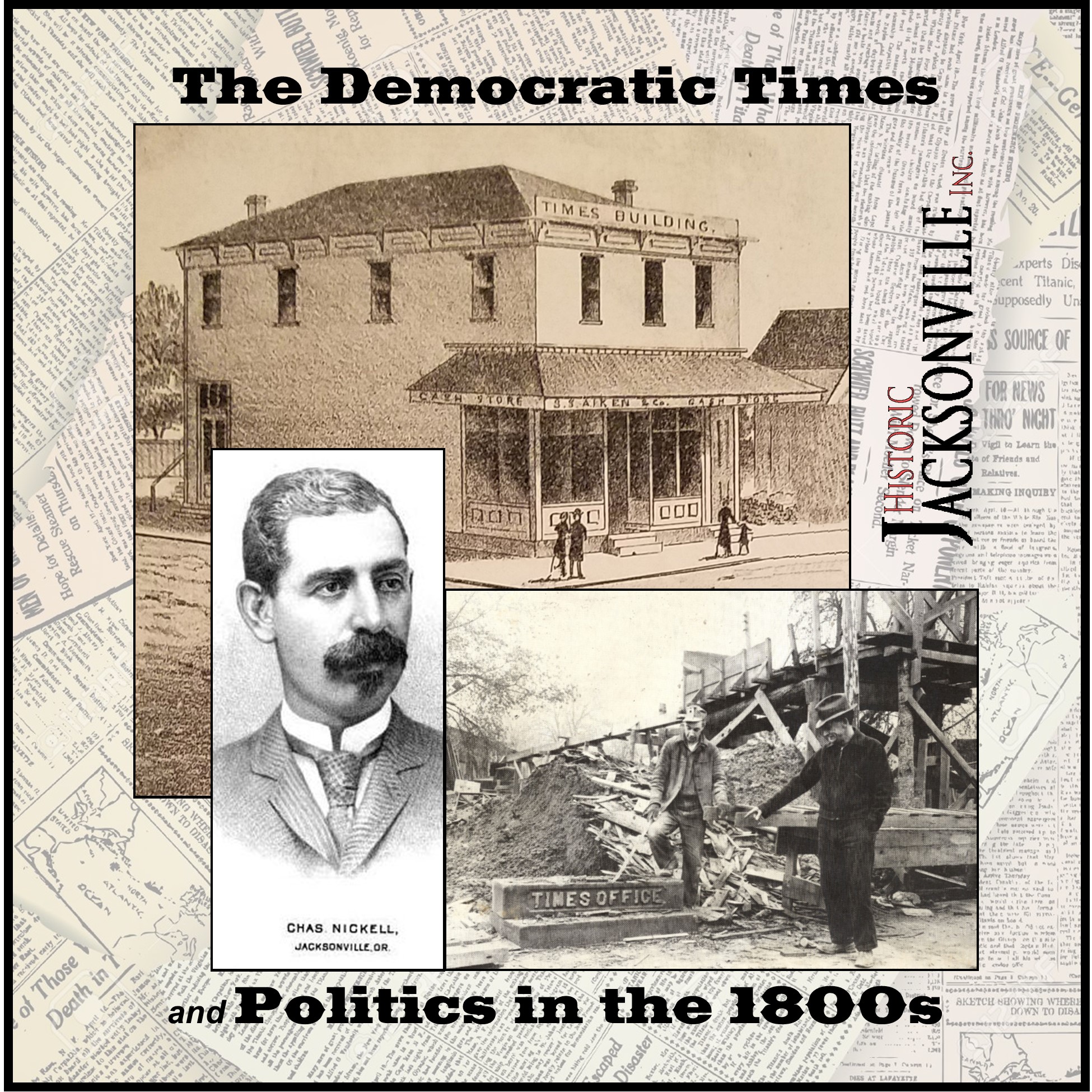

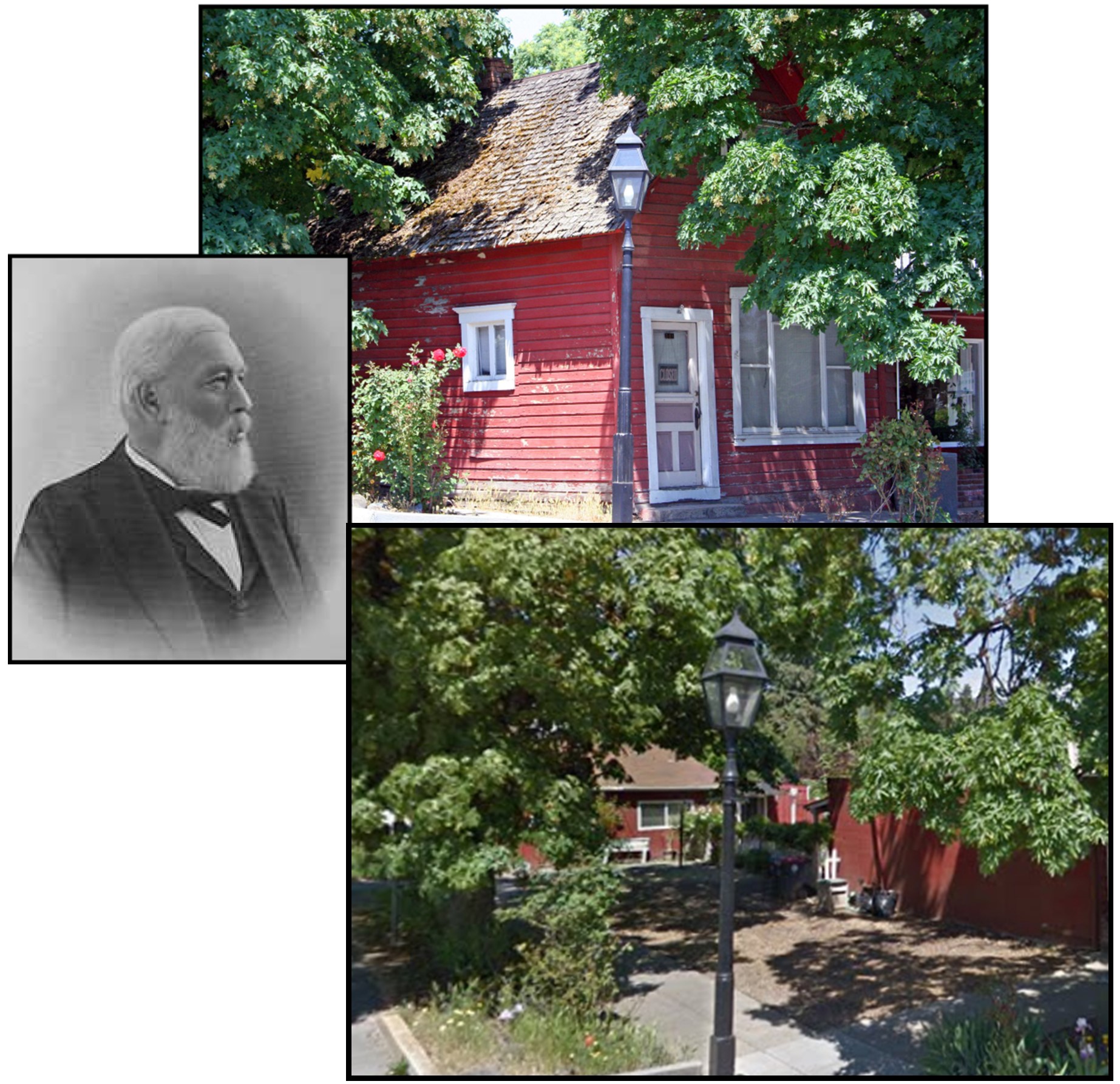

Democratic Times Newspaper #1

Early Jacksonville had a succession of newspapers over the years, many of them competing and espousing opposing political viewpoints. When the Democratic News plant was destroyed in the fire of 1872, it rose again as the Democratic Times. Initially housed in the Orth Building on South Oregon Street, the Times soon outgrew that space and established its own offices at the corner of C and North 3rd streets. The Times lasted into the early 1900s when it merged with the Southern Oregonian. Depression era miners of the 1930s uncovered the Times door step as they undermined almost every inch of Jacksonville. The current private residence was built as a rental property in the 1930s over one of these old mine shafts.

Democratic Times Newspaper #2

A reader responded to last week’s history trivia about the Democratic Times building at the corner of C and North 3rd streets, noting that anyone who thinks political opinion is too radical in 2020 needs to look back to the election of 1876 and the Times’ coverage. So, for this week, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. thought we would follow that train of thought and expand on Jacksonville’s Democratic Times. The paper was established by Charles Nickell, a boy genius, who became sole owner at the age of 17. It was a solid success from as early as 1869 right down to the 20th Century. Aside from Portland papers, it had the largest newspaper circulation in Oregon. Nickell’s editorial policy embraced the Democratic party and championed its leaders. [This was before the Republican and Democratic parties switched policy positions and the Democratic party, which had been pro-Confederacy, continued in that vein, promoting states’ rights and opposing civil rights for African Americans.] No one could accuse Charles Nickell of being objective. Today he would be sued out of business before nightfall, but at that time, readers apparently appreciated an editor who told them how to think. Nickell seems to have enjoyed the tacit dispensation to do just that. He was a distinguished and influential citizen until the turn of the century when he unfortunately brought about his own downfall by entering into some shady deals that were beyond the limits of the law. But that’s another story….

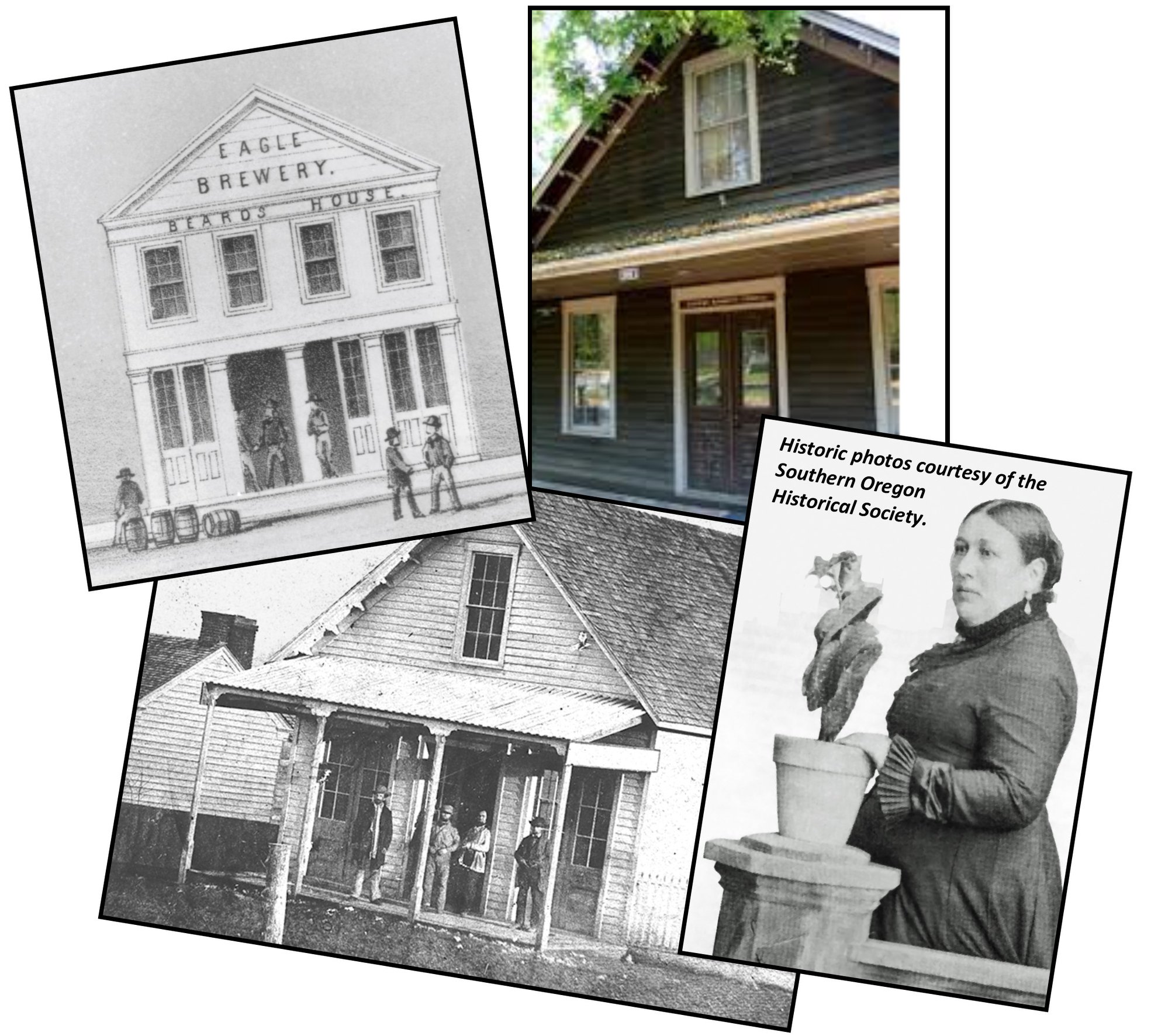

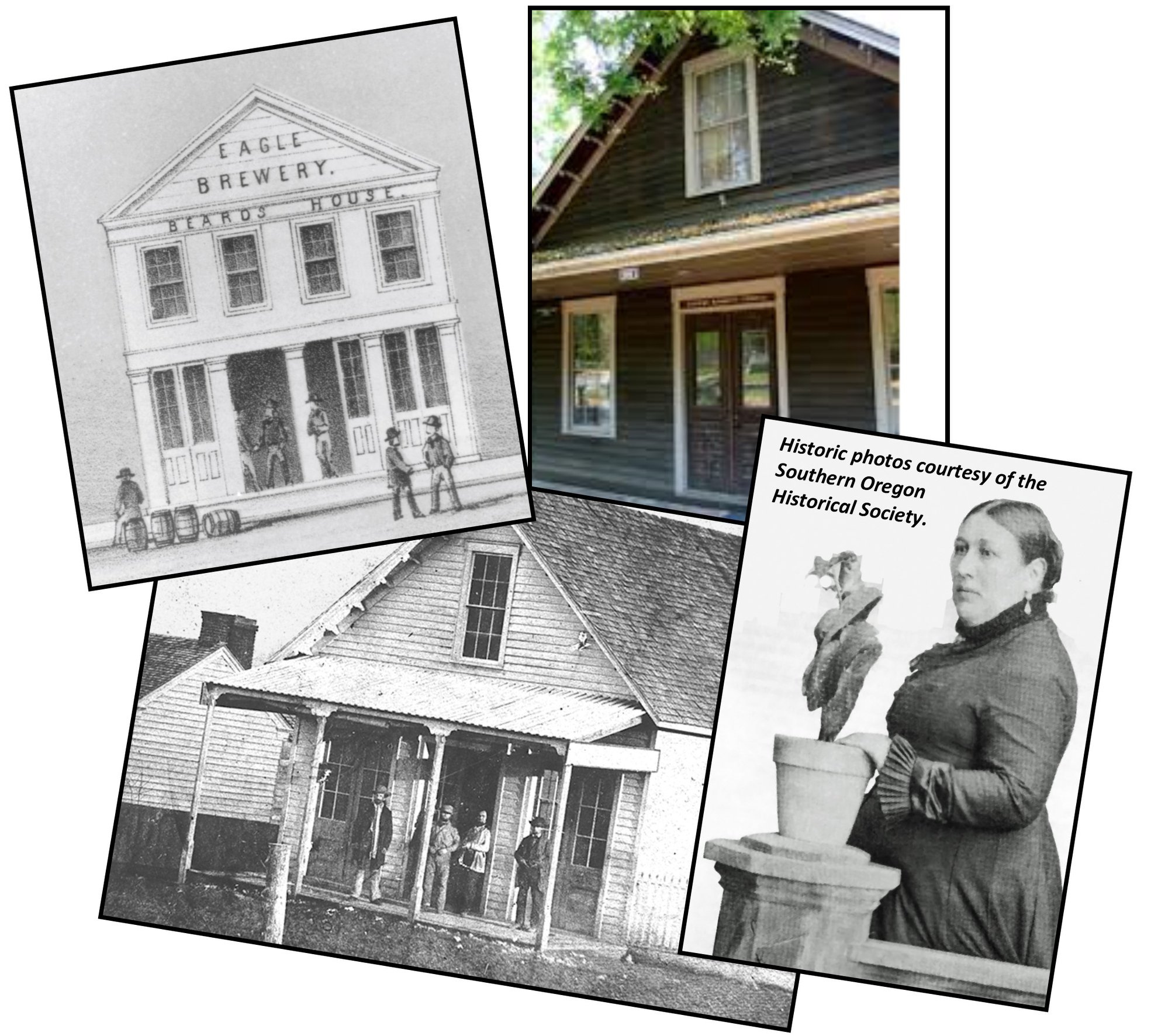

Eagle Brewery Saloon

Early Newspapers

Excelsior Livery Stable

The northwest corner of Oregon and C streets was home to the Excelsior Livery Stable for over 40 years. It can be seen in today’s picture as the tall building behind Jacksonville’s train station, now Visitors Center. Established by Sebastian Plymale in 1866, it was purchased by his brother William in 1875 when he, wife Josephine, and family moved into Jacksonville from the Applegate. The Plymales provided transportation for fellow citizens by driving and renting out horses and buggies to paying customers. Josephine assisted William with the enterprise, even driving horse teams for clients when needed. She was described by one such client as a “gallant lady pilot, efficient and successful at her business.”

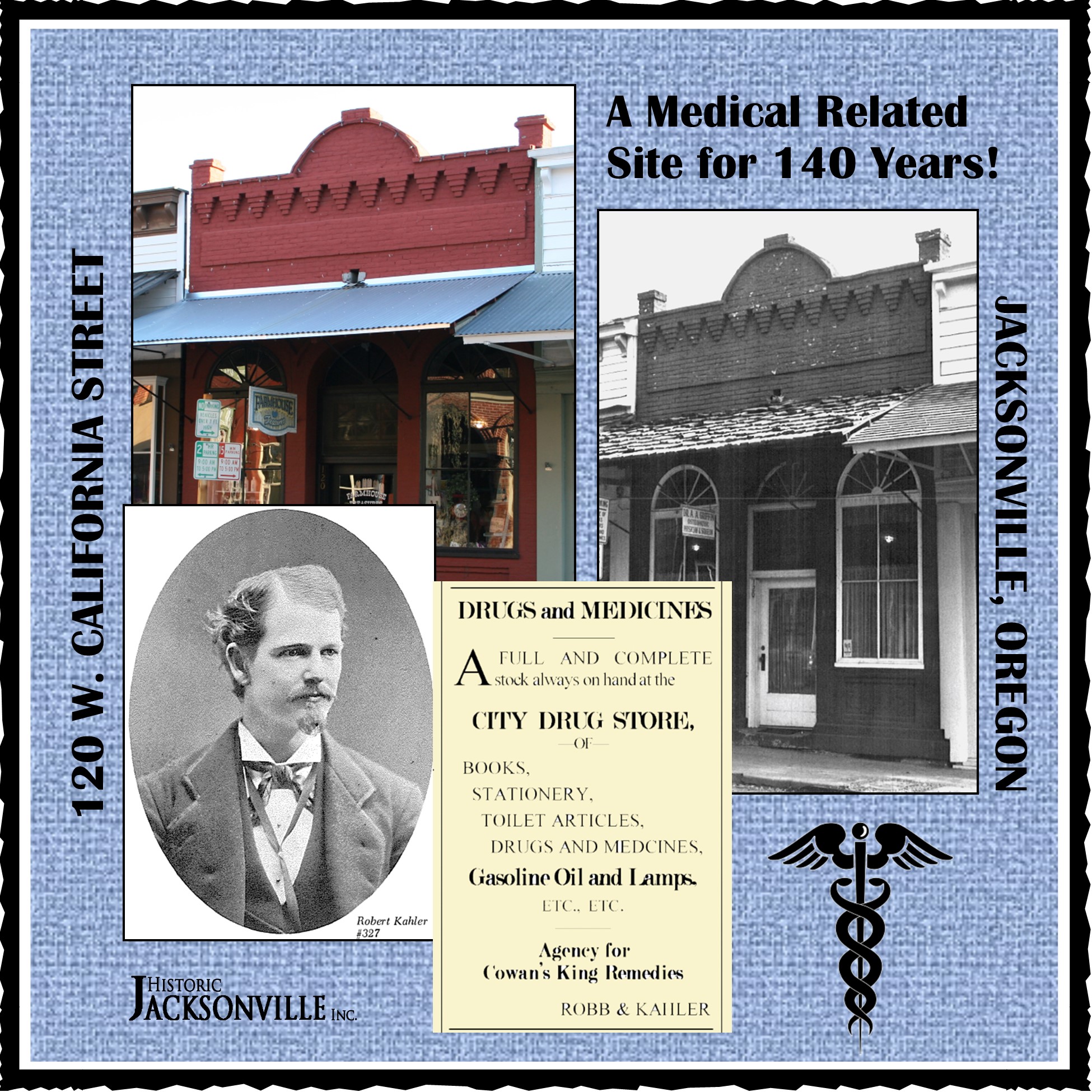

Farmhouse Treasures Building

Farmhouse Treasures at 120 West California Street is located on one of the few spots in Jacksonville that was used continuously for medical related purposes for almost 140 years. G.W. Greer, “physician and surgeon,” operated an office at this site as early as 1855. By 1862, Dr. L.S. Thompson had joined Greer in dispensing drugs and medicines. In 1868, Sutton and Stearns were carrying “everything usually found in a first class drug store.” Three years later Robert Kahler owned the City Drug Store. Kahler had the current 1-story brick building constructed in 1880, shortly after taking Dr. J.W. Robinson (shown here) into partnership. As late as the 1980s it was an osteopath’s office.

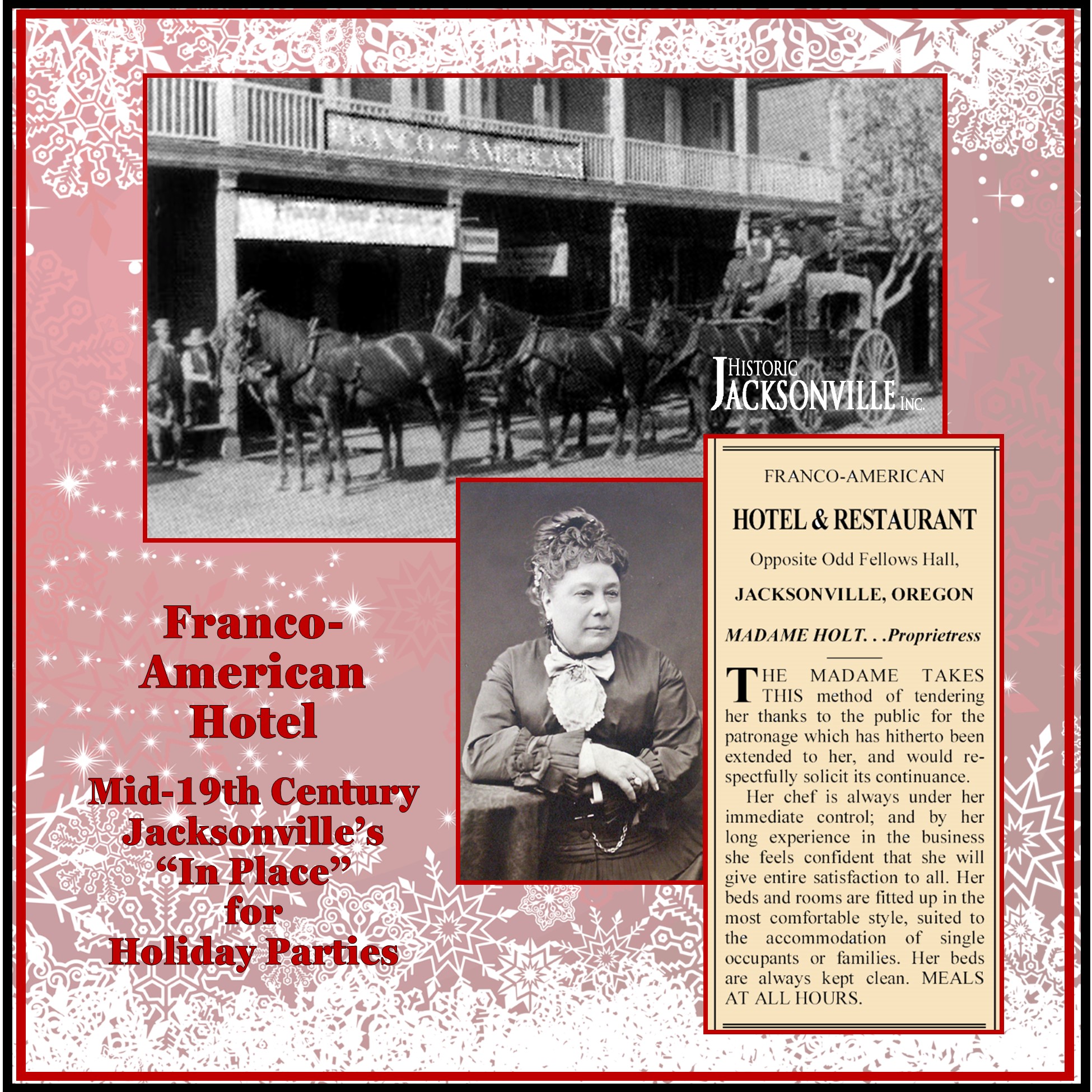

Franco-American Hotel

The Christmas parties have begun, and one of the favorite establishments for holiday celebrations in early Jacksonville was the Franco-American Hotel. You may be familiar with Madame Jeanne DeRoboam Holt’s grand brick U.S. Hotel which she opened in 1880, but over 20 years earlier she had established the Franco-American Hotel.

It was located at the southwest corner of Oregon and Main streets in Jacksonville where the Jacksonville Inn cottages are now. The Franco-American became a famous regional hostelry and the leading hotel and stage stop in Jacksonville, noted for its “table d’hôte,” and holiday balls “worthy of the patronage of epicures and connoisseurs.”

It burned to the ground in 1886.

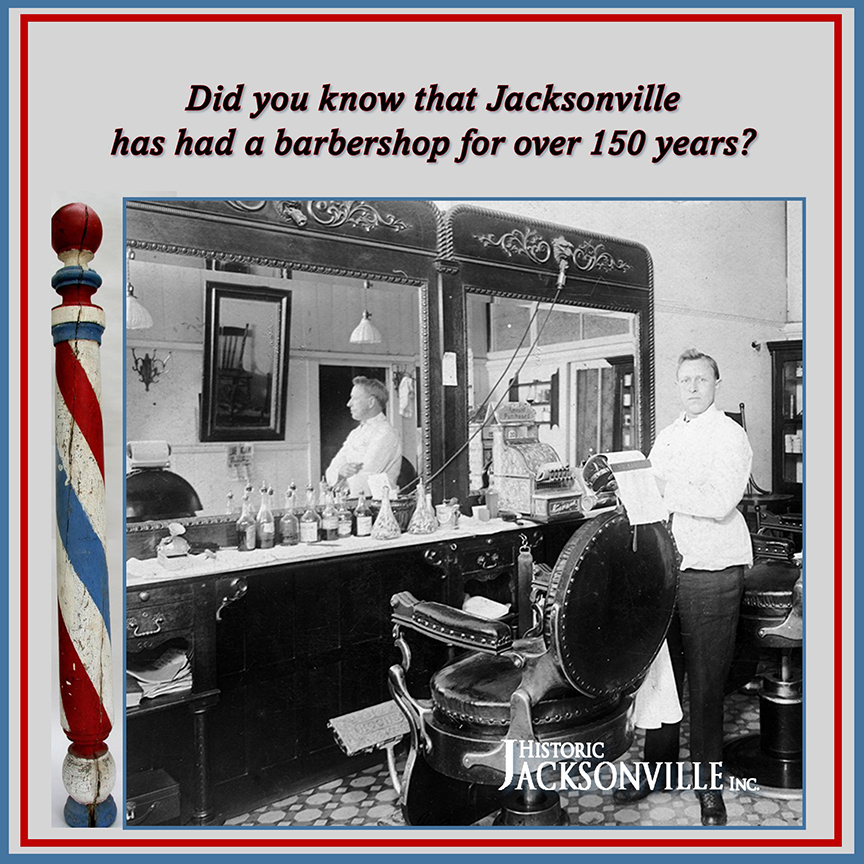

George Schumpf Barbershop

In 1874, George Schumpf erected the 1-story arcaded brick building at 157 W. California Street (no doubt simultaneously with its “twin” next door) after a raging fire destroyed most of the block’s original wooden structures in spring of that year. Schumpf, a native of Alsace, Germany, was probably Jacksonville’s most successful and longest established barber. As early as 1868, he may have had a barbershop in this building’s wood frame predecessor, possibly part of the notorious El Dorado Saloon. In fact, according to the Oregon Sentinel, the 1874 fire may have originated over Schumpf’s store in the “Town Club Room.” But by November of that year, Schumpf was occupying his new establishment. In addition to shaves and haircuts for men (and women), patrons could also enjoy “neat bathing rooms and bath tubs” where they could obtain “a bath, hot or cold,” and a boot black stand where they could have their shoes shined in a “most artistic style.”

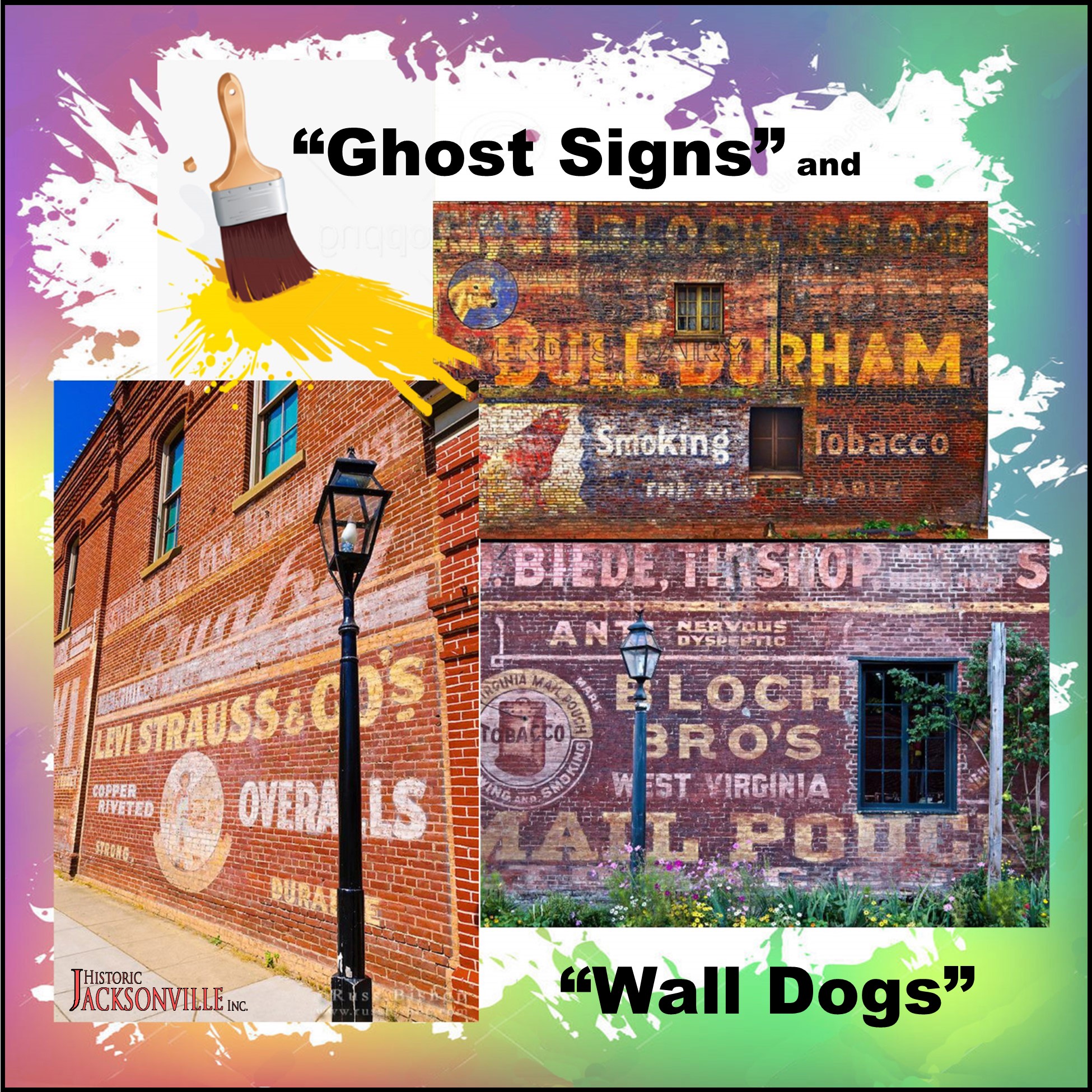

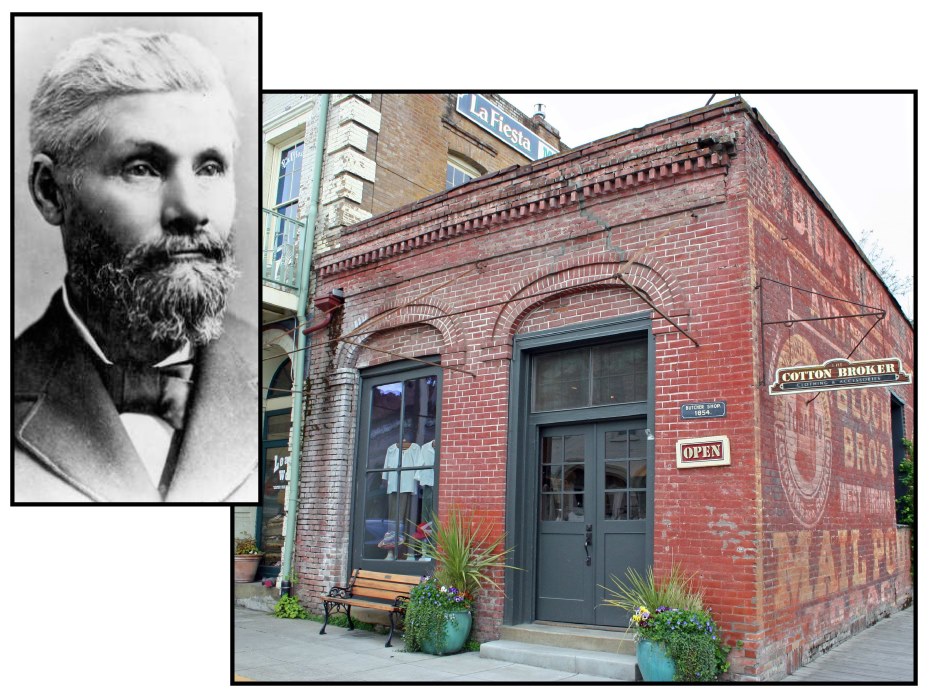

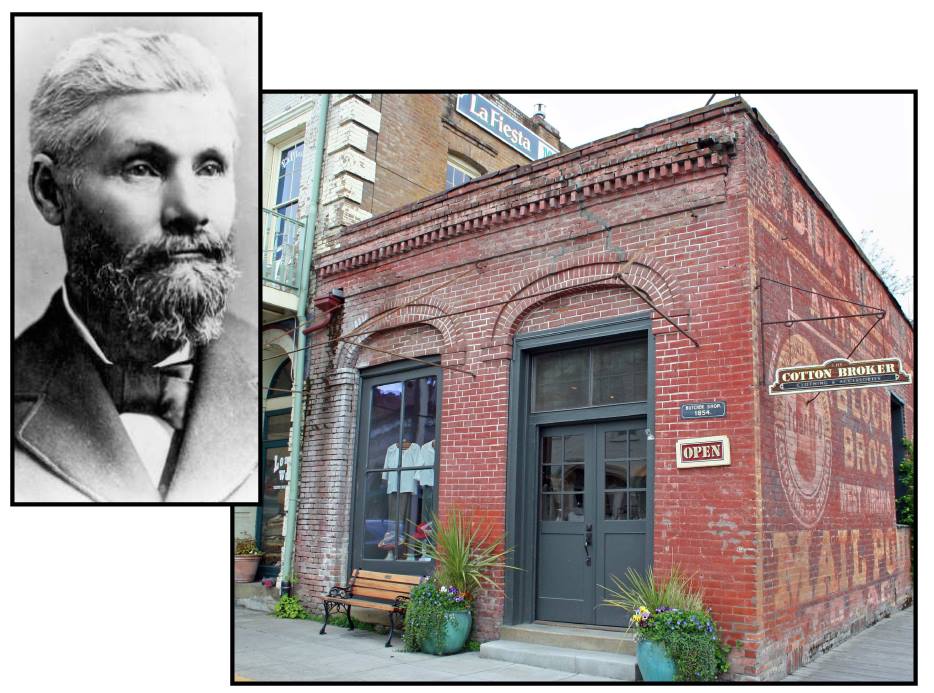

Ghost Signs

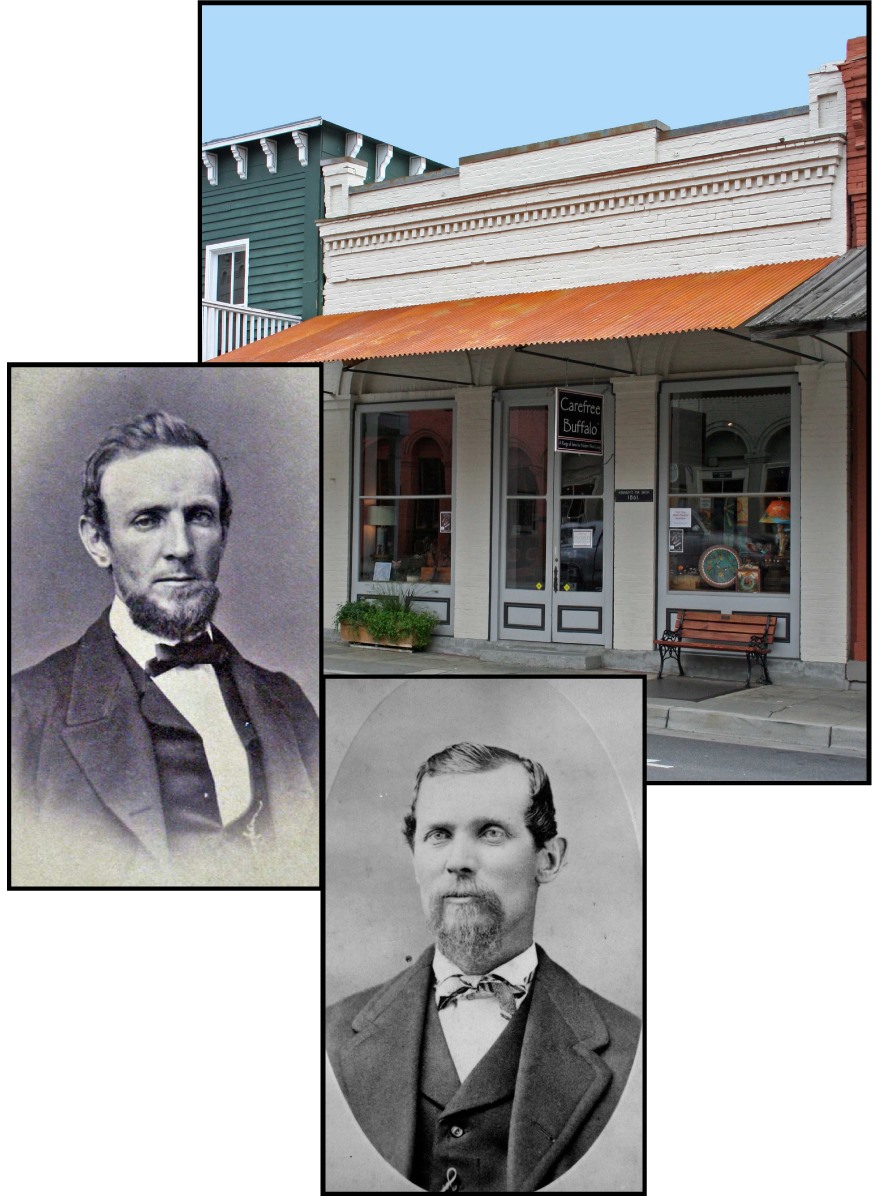

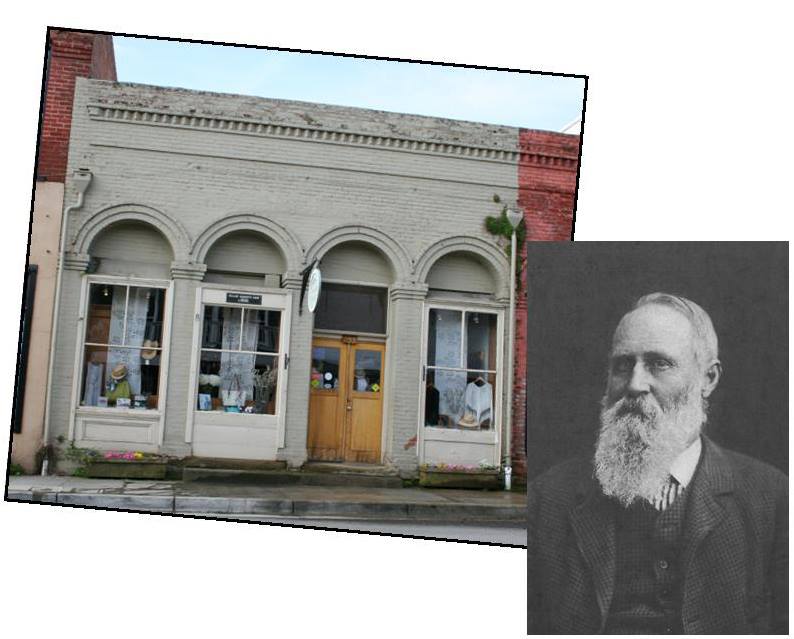

Haines Building

Haines’ Variety Store

Israel and Robert Haines’ variety store, constructed in 1861 at the corner of California and Oregon streets, replaced a wooden building they had occupied since arriving in Jacksonville 7 years earlier. This one story brick structure is one of the oldest commercial buildings to survive 3 major fires that ravaged the town. The construction expense may have over extended the brothers financially, since by 1862 Israel was reading law and Robert was studying medicine. Robert relocated to San Francisco. Israel (shown here) moved to eastern Oregon where he became a prominent Baker City lawyer and politician and founded the town of Haines.

Happy Alpaca

Early in 1852, soon after news of the gold discovery in Jacksonville spread to California, Kenny and Appler, two packers from Yreka, established the first trading post on this site. They stocked it with a few tools, clothing, boots, “black strap” tobacco, and a liberal supply of whiskey, essential items for an infant gold mining camp.

By 1856, their tent had been replaced by a wooden store and then by a brick storehouse. In 1860, merchants Abraham and Newman Fisher acquired this prime corner location for their dry goods and general merchandise store. Fires consumed their stores in both 1868 and 1874. Despite a $28,000 loss in the latter conflagration, the Fisher brothers rebuilt, and the 1874 A. Fisher & Brothers structure still stands today—although it has been through quite a few changes.

One of its longest tenants was the Marble Corner Saloon also known as the Marble Arch Saloon. The saloon occupied the building from around 1890 to 1934. The saloon was presumably named after the Jacksonville Marble Works which in 1888 was located across the street…or because the saloon’s recessed entryway was tiled with marble from its neighbor.

The Scheffel family purchased the building in 1868 and moved into it in 1871. It was Scheffel’s for the next 50 years, first an antique store then a popular specialty toy store. We’re delighted that the Kranenburg and Butler families are continuing the tradition of being a children’s toy and specialty story—especially since the Happy Alpaca is now the only one in the Rogue Valley!

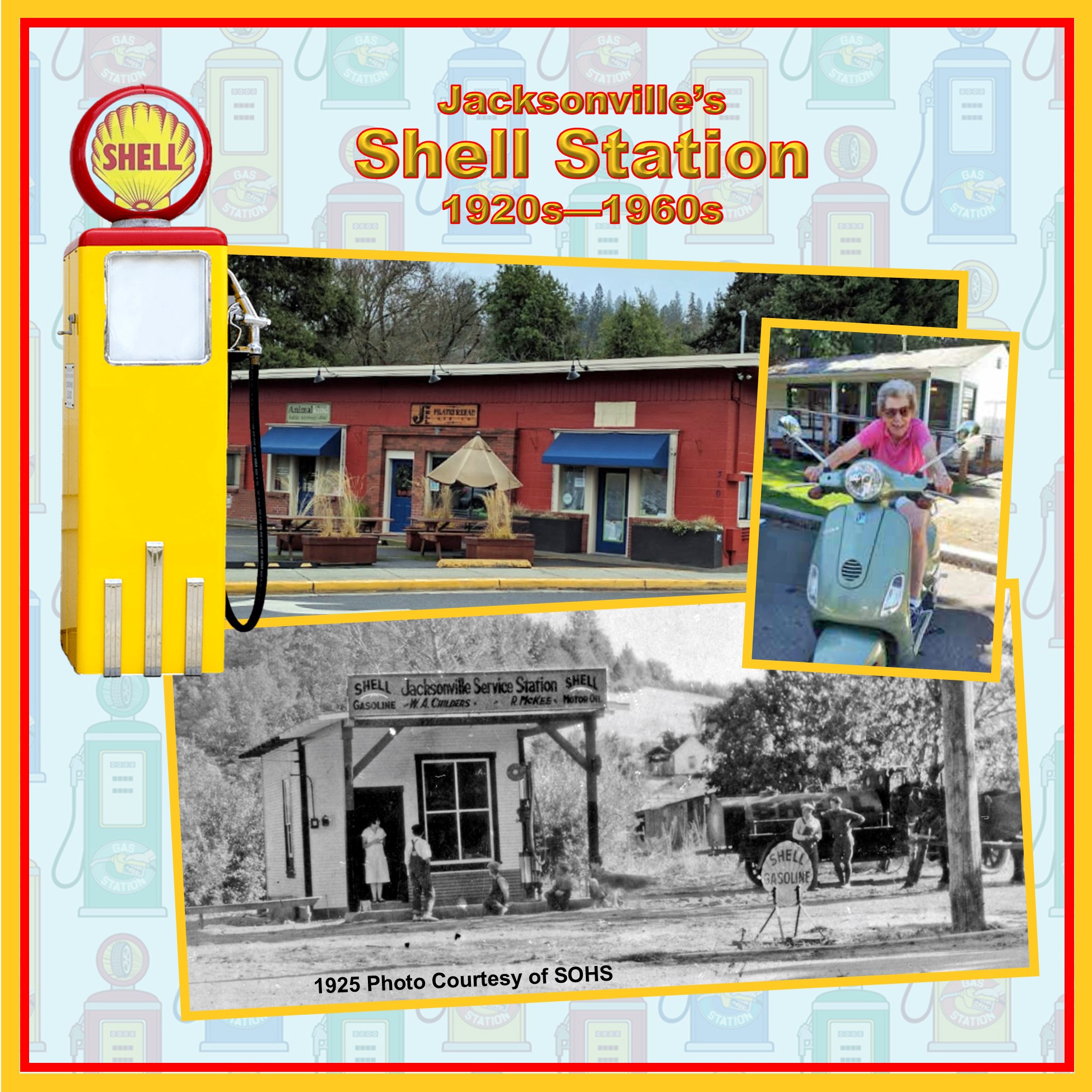

Henspeter’s Service Station and Motor Court

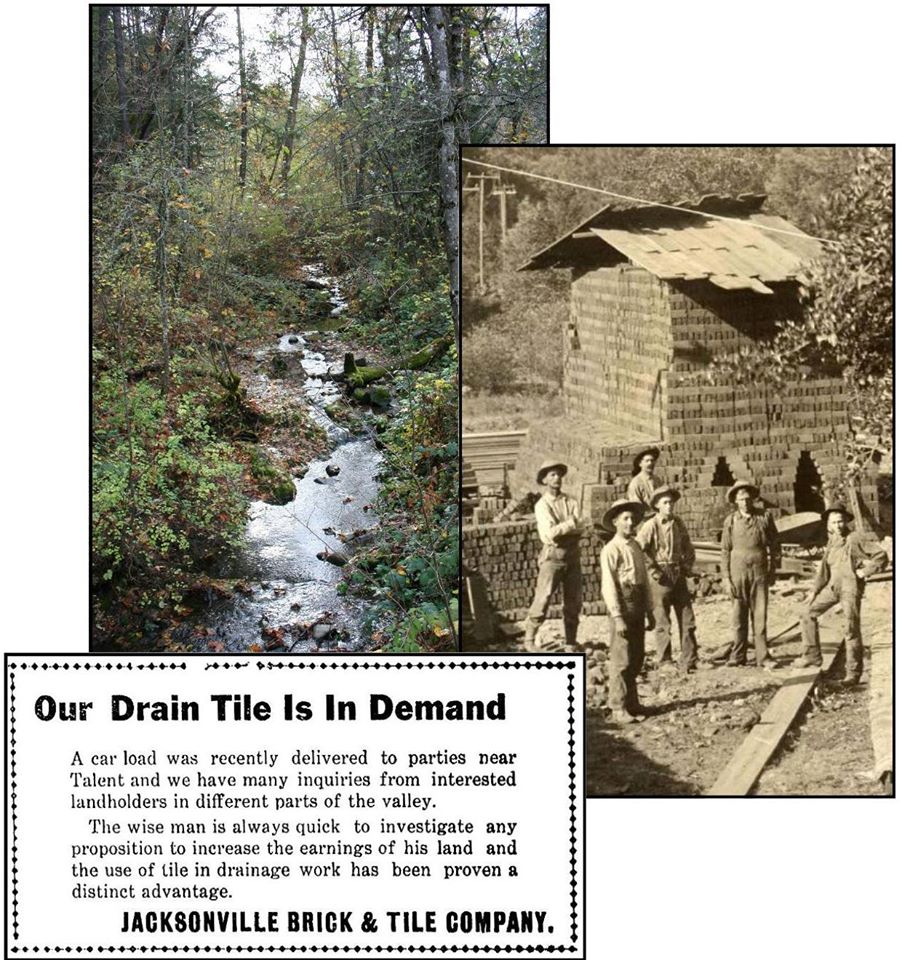

Jacksonville Brick & Tile Co.

November 8, 2016

The banks of Jackson Creek across from Mary Ann Drive and Reservoir Road are the site of The Jacksonville Brick & Tile Co., one of the biggest brick kilns in Southern Oregon. Incorporated in 1908 by German immigrant Peter Ensele and his sons, the brickyard could burn 200,000 bricks every 6 weeks. The steep banks of nearby Jackson Creek had previously been the site of a major gold strike. When the gold played out, the rich clay supplied the bricks for major projects in Jacksonville, Ashland, and Medford. But with gold flakes still sprinkled throughout the site, “rich clay” took on a new meaning. To this day, flakes of gold still work their way our of Jacksonville Brick & Tile Co. brick buildings.

The shop itself has moved around a bit for most of the time it has stayed in its current vicinity, moving between 135, 145, 155, and 157 W. California Street and the ground floor of the 1870s Masonic Hall.

One of the longest serving barbers, and the first town barber “with training,” was George Schumpf. In 1873 he purchased Blackwell’s barbershop lodged in the notorious El Dorado Saloon. The saloon stood on the corner of California and Oregon streets from 1852 until the building was destroyed in the town fire of 1874 along with most of the town’s early wooden structures,

Schumpf immediately rebuilt, erecting the brick structure at 157 W. California, and by November of that year he was occupying his new brick establishment. In addition to shaves and haircuts for men (and women), patrons could also enjoy “neat bathing rooms and bathtubs” where they could obtain “a bath, hot or cold.” Although Schumpf lost ownership of his shop in in 1882 due to poor business speculations, he remained “the town barber” until his death in 1897.

We know that a Mr. Murphy was operating the barbershop in 1911 at the current site, and that a William Puhl was subsequently the barber (and subject to a rather messy Halloween trick—see our Holiday History website page). In the 1930s the barbershop occupied a shop facing S. Oregon Street in the Masonic Hall, and in the 1950s, the barbershop briefly occupied a building at the corner of North 4th and California (our current People’s Bank) before returning to its current location.

Jacksonville Brickyard

The banks of Jackson Creek across from Mary Ann Drive and Reservoir Road were the site of The Jacksonville Brick & Tile Co., one of the biggest brick kilns in Southern Oregon. Incorporated in 1908 by German immigrant Peter Ensele and his sons, the brickyard could burn 200,000 bricks every 6 weeks. The steep banks of nearby Jackson Creek had previously been the site of a major gold strike. When the gold played out, the rich clay supplied the bricks for major projects in Jacksonville, Ashland, and Medford. But with gold flakes still sprinkled throughout the site, “rich clay” took on a new meaning. To this day, flakes of gold still work their way out of Jacksonville Brick & Tile Co. brick buildings.

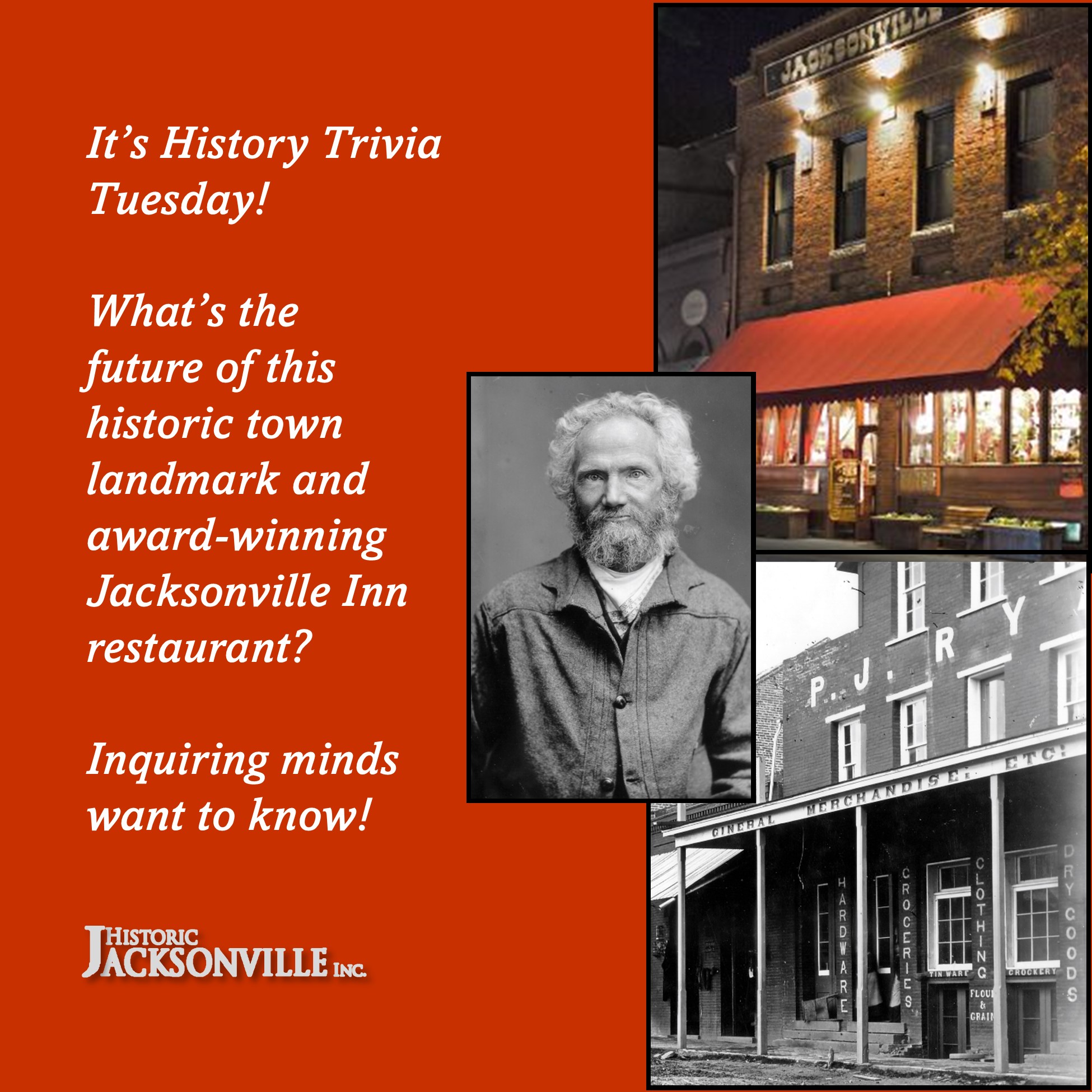

Jacksonville Inn Origins

The building we know today as the Jacksonville Inn was originally P.J. Ryan’s storehouse.

The building itself was originally P.J. Ryan’s storehouse. Irish immigrant Patrick Ryan was early Jacksonville’s most prolific builder of “fire-proof” brick commercial buildings. In 1861 he constructed a 1-story brick mercantile store at 175 E. California, variously occupied by Judge’s Saddlery, H. Bloom, and “M. Menzer Gen’l Mdse.” Ryan himself occupied the building when it burned in the April 1873 fire. He suffered one of that fire’s heaviest losses—the building itself plus $30,000 in merchandise.

Within a year, Ryan was erecting a 2-story brick mercantile warehouse on the previous foundation. Months later, the building “continued heavenward” with a 3rd story wooden “pent house,” (later removed), making it the tallest building in Oregon. The Oregon Sentinel proclaimed it to be “as fine a building of the kind as there is in any town this size in the state.” Ryan’s store was on the ground floor and his living quarters on the second floor. Who occupied the “penthouse” is unknown.

Over the next century, the building was occupied by a mercantile, the post office, a flour and feed store, and other entities until, like many of Jacksonville’s commercial structures, it became derelict after the railroad bypassed Jacksonville and the county seat was moved to Medford.

In the 1960s, Mayor Jack Bates purchased the building as part of Jacksonville’s celebrated revival which created the town’s National Historic Landmark District. In 1976, Jerry Evans and his wife, Linda, purchased the Jacksonville Inn. Jerry dedicated the next 45 years of his life to keeping the renowned inn and restaurant up and running. But in 2021, at age 85, he decided to move on to other pursuits.

According to the current owners press release, the restaurant is currently up for lease, but the Inn and wine shop will continue in operation. Let’s hope that there will be new owners who reopen the restaurant and that the tradition of Jacksonville Inn hospitality continues into the foreseeable future!

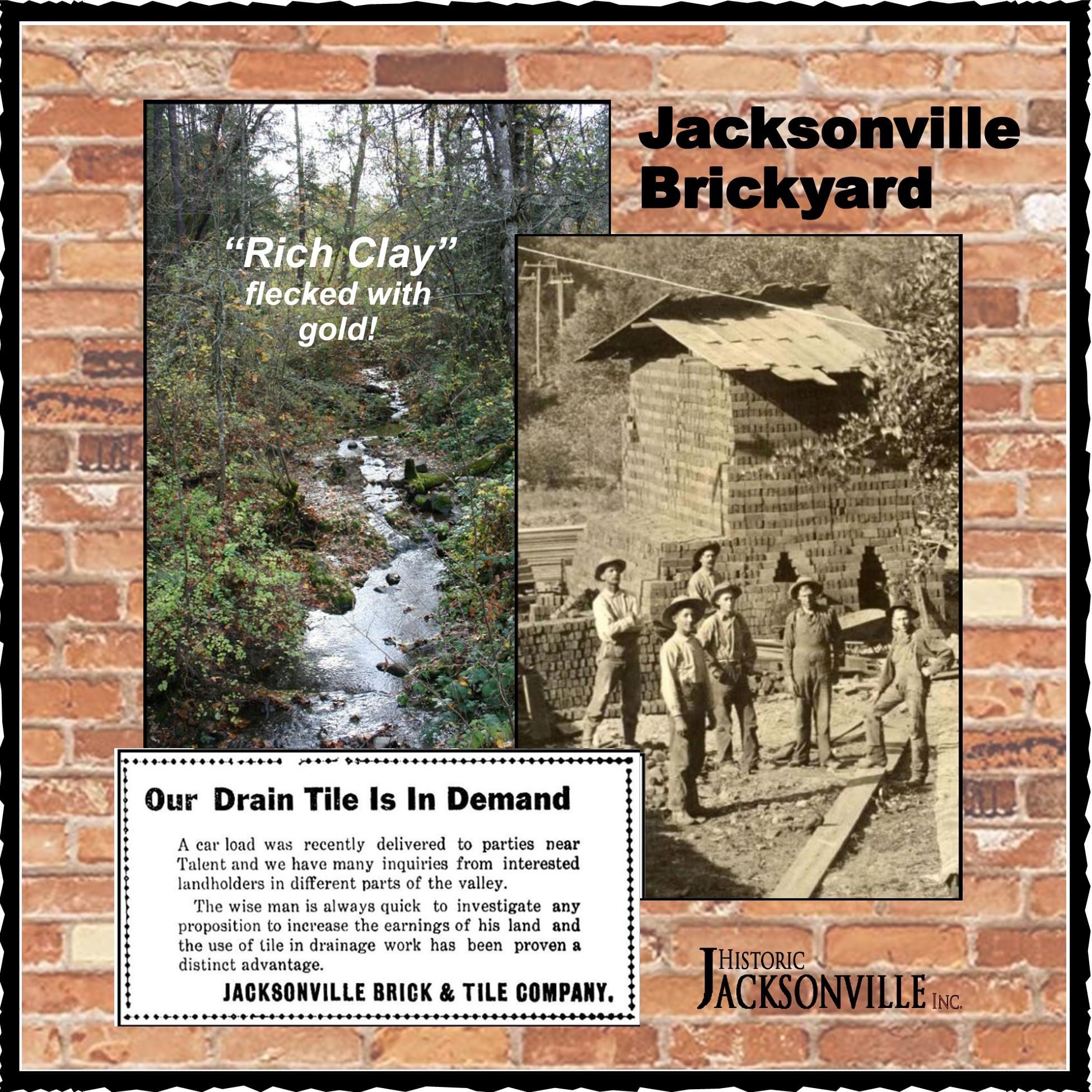

Jacksonville Marble Works

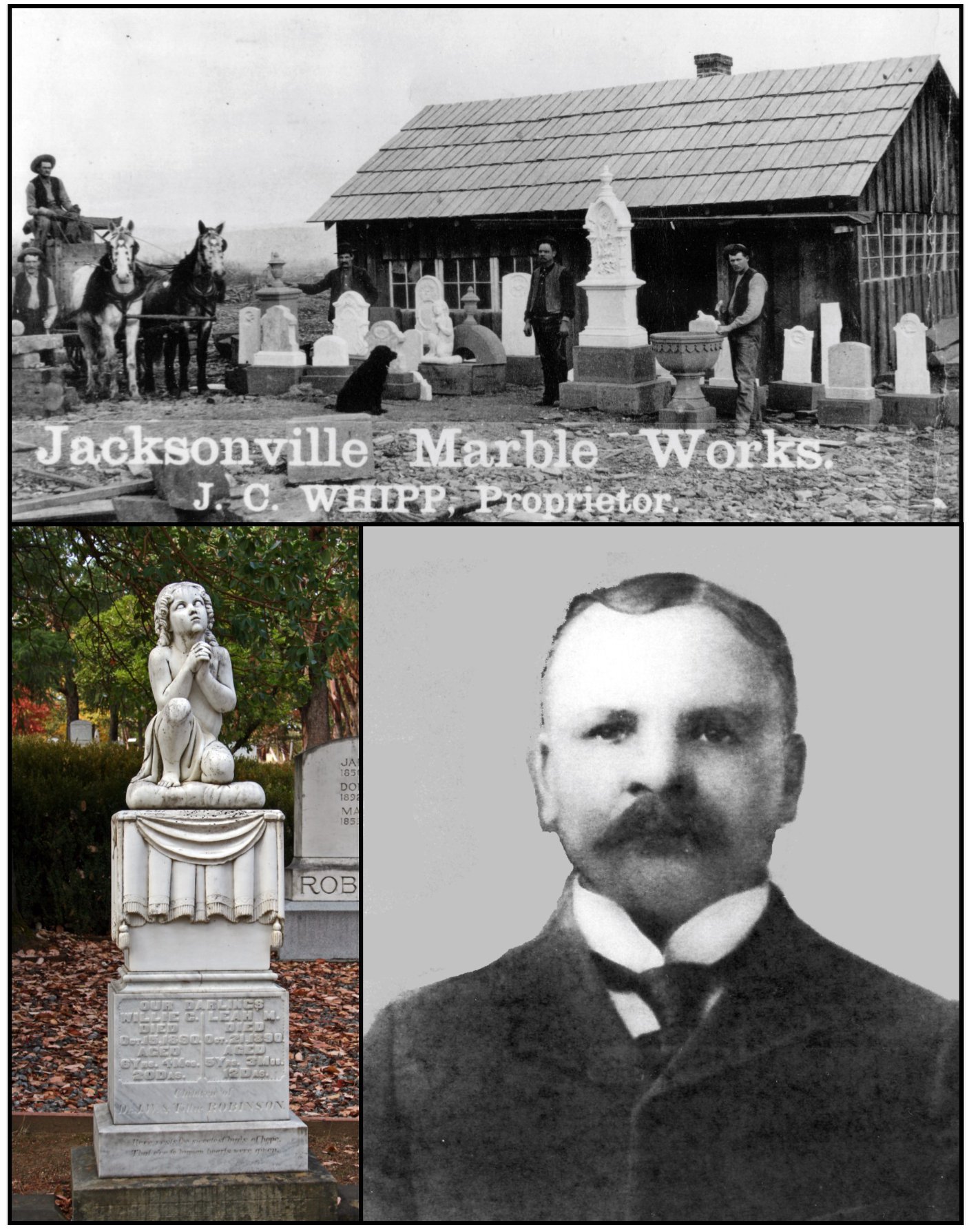

Jacksonville Mercantile Store

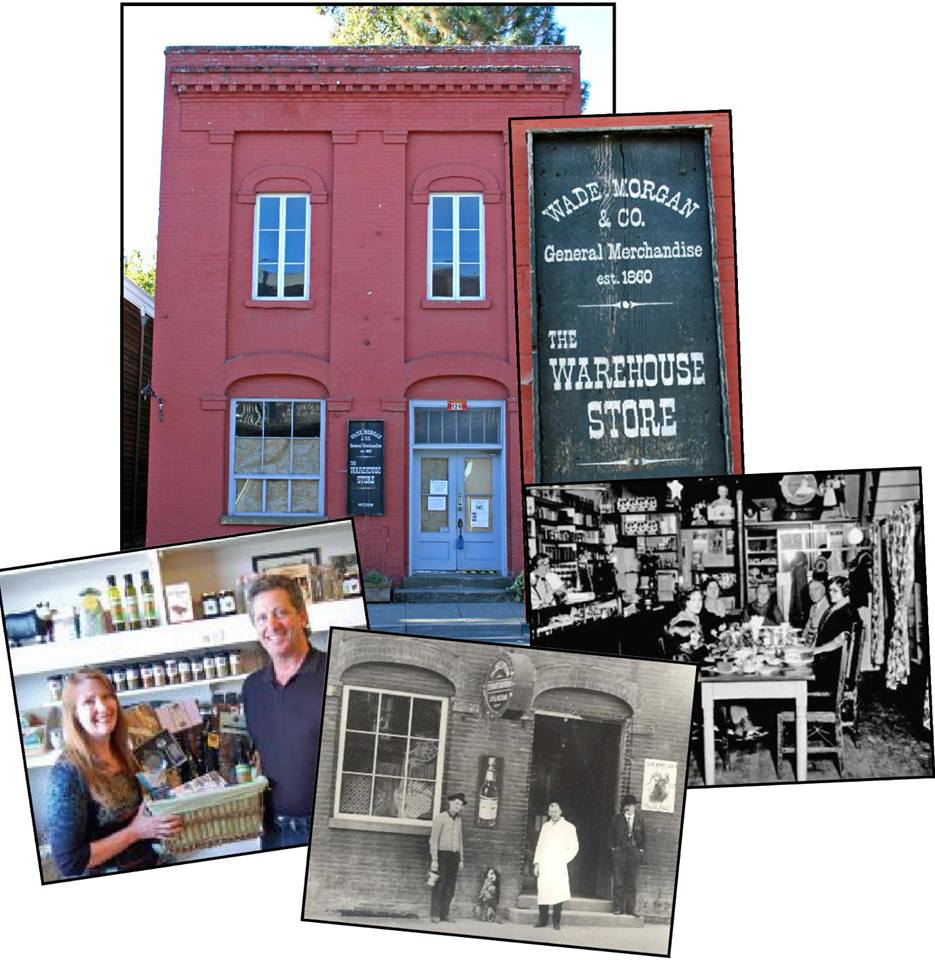

The brick building at 120 E. California Street was probably the second 2-story brick building erected in Jacksonville. Constructed around 1861, it’s historically known as the Wade, Morgan & Co. building after some of its earliest tenants. However, it was actually commissioned by P.J. Ryan, the Irish immigrant who was the early town’s most prolific owner and builder of “fire-proof” brick commercial buildings. Ryan himself occupied the building in the early 1870s but by the end of the decade the Oregon Sentinel newspaper occupied the top floor and the ground floor had been converted to a saloon. Today it’s home to the Jacksonville Mercantile, a specialty store for gourmet food and gifts.

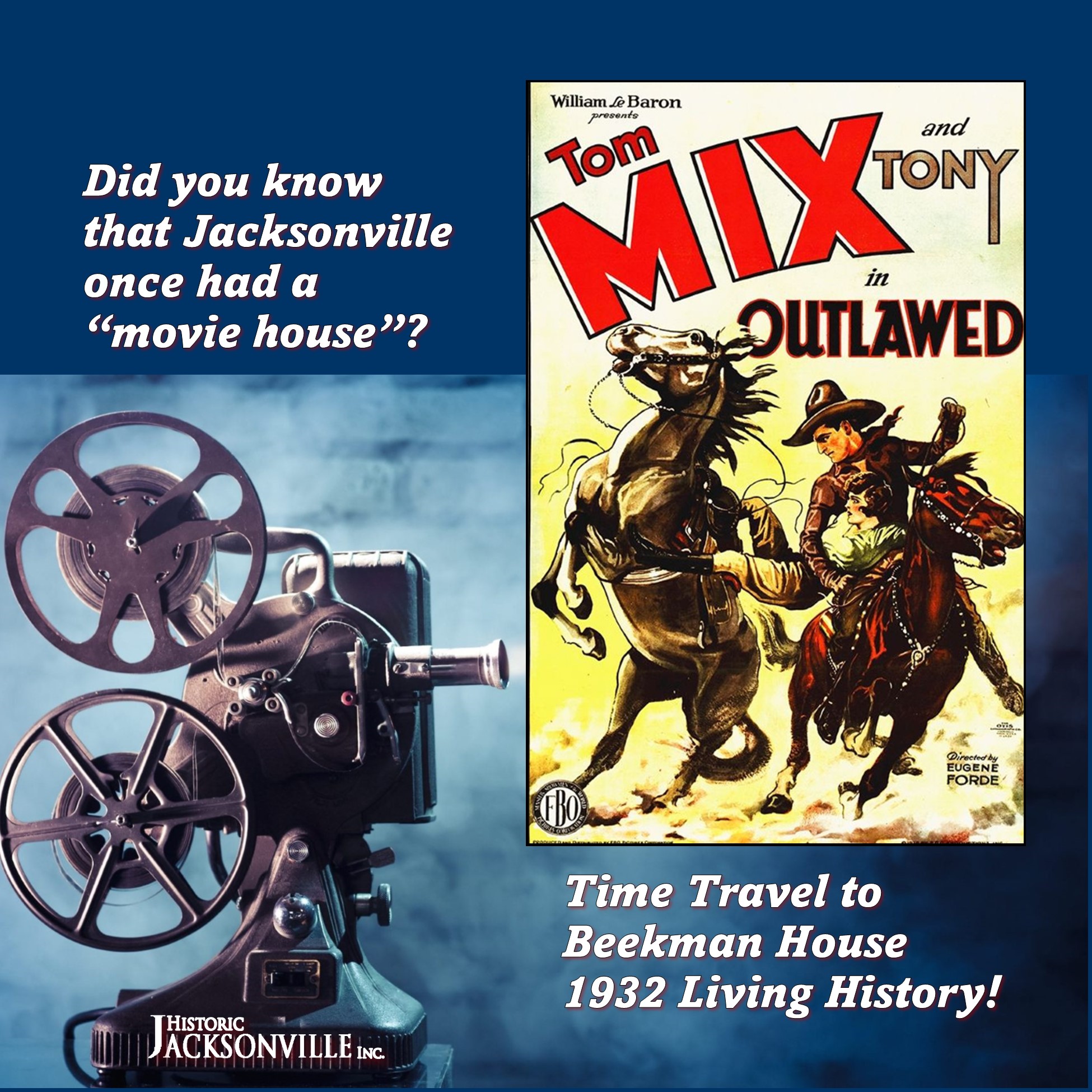

Did you know that Jacksonville once boasted a movie theater? On November 21, 1929, “Outlawed,” starring cowboy Tom Mix and his horse Tony, opened Felton Franks’ new “movie house.” Located in the Kubli building at 115 W. California, it boasted a stage, a sloping floor, “attractive decorations,” and a seating capacity of 150. Franks promised shows 4 times a week, continuous performances from 7 to 11pm, and 3 complete weekly changes of program featuring “the very best of the big silent pictures” from Paramount, Universal, and FBO.

However, Franks’ timing was off, following so closely on the heels of the stock market crash of 1929 which ushered in the Great Depression. The movie house lasted into the early 1930s, but closed for lack of audience. Even though movies were a popular escape from the Depression, Jacksonville’s population had fallen to under 700 and many were “on the dole,” i.e., welfare.

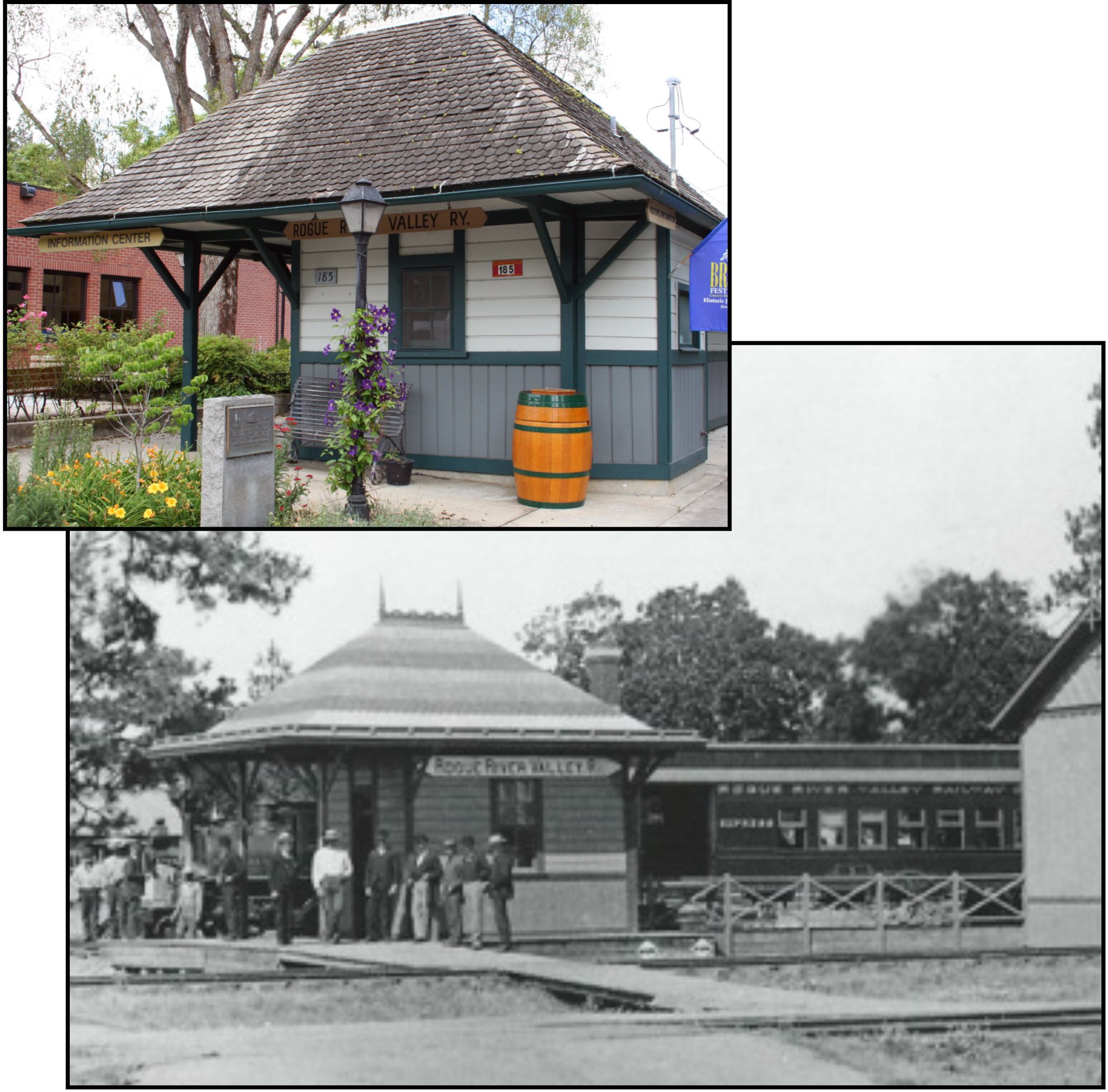

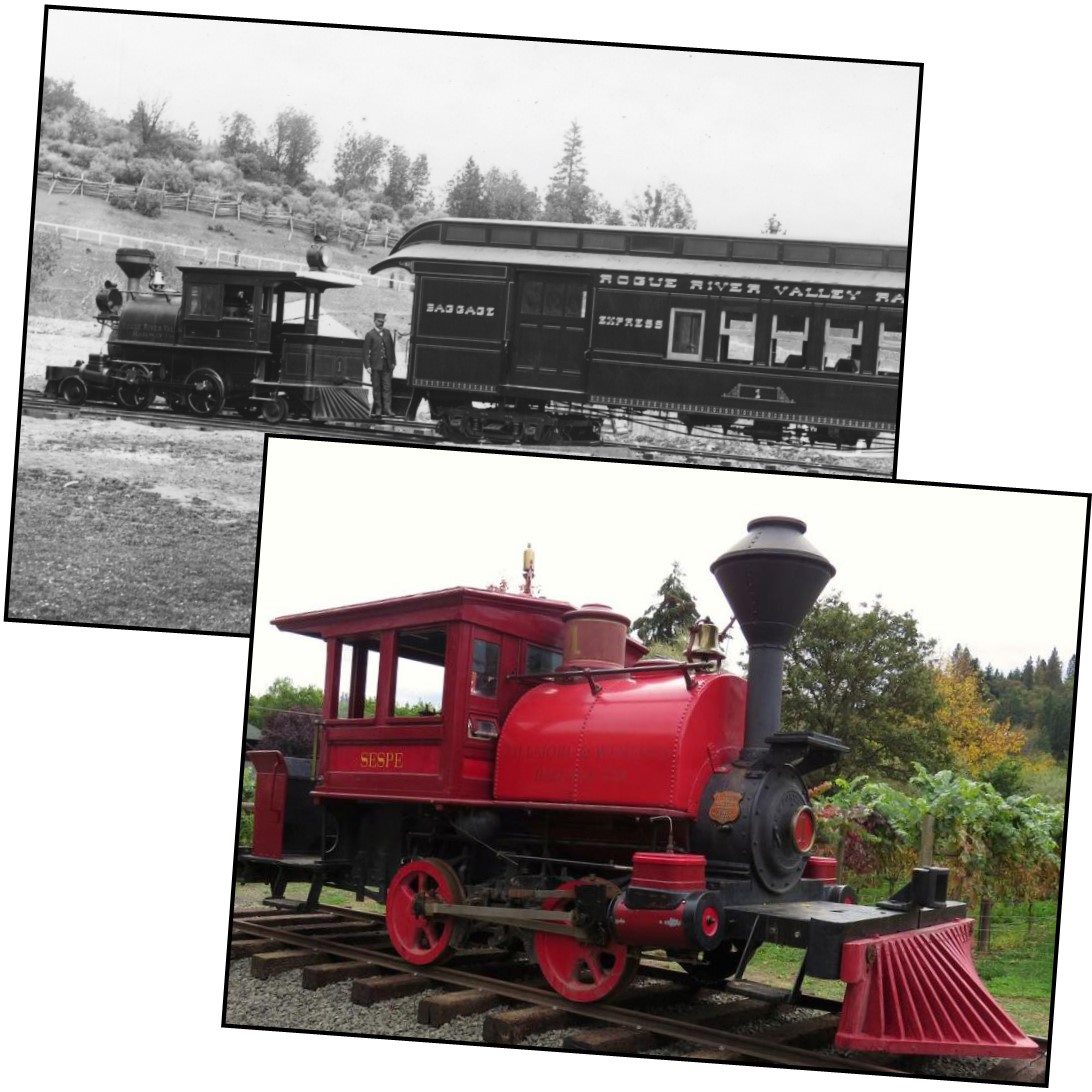

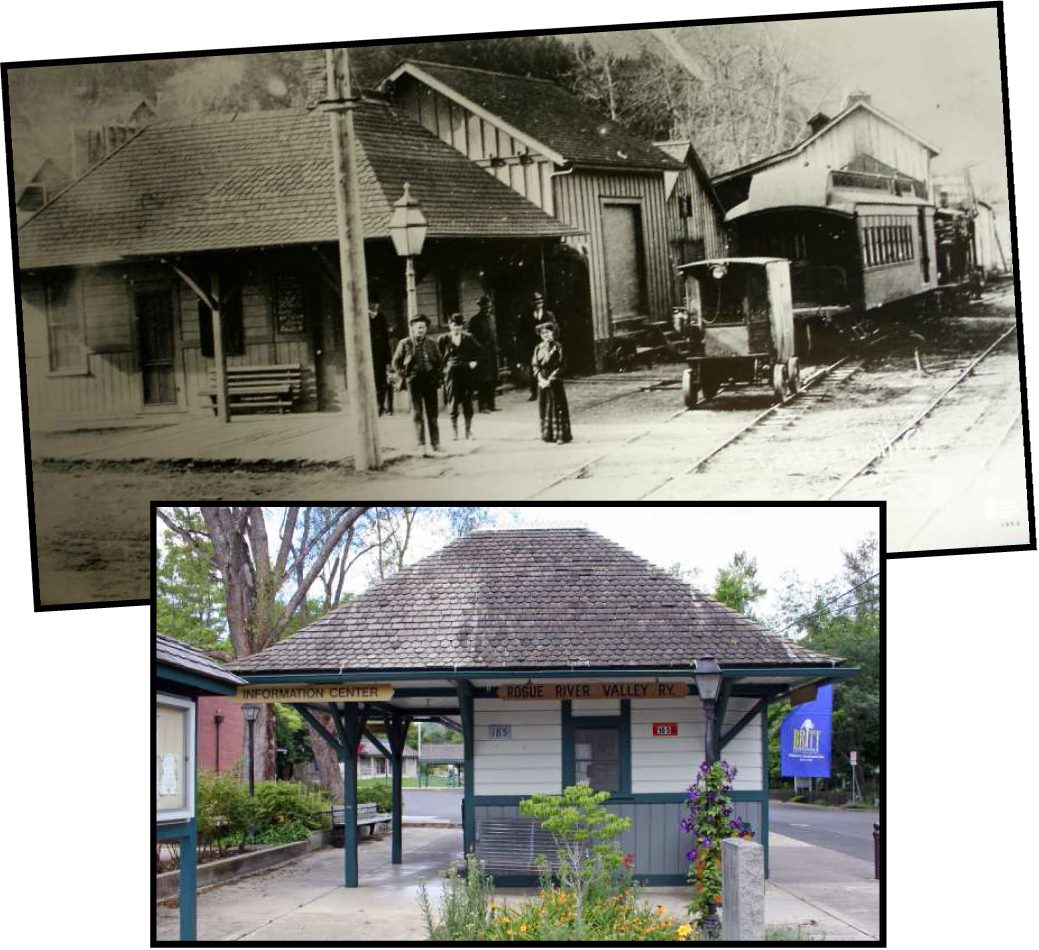

Jacksonville Train Depot #1

When the Oregon & California railroad bypassed Jacksonville in 1884 in favor of the flat valley floor, the town struggled to retain its role as the hub of Southern Oregon commerce, government, and social life. Residents funded a spur line to connect the city to the main railroad in Medford, and in May of 1891, the Rogue River Valley Railway’s small steam locomotive, Engine No. 1, pulled into the Jacksonville depot. The railroad survived until 1925, but after a year, the undersized engine was relegated to hauling a single pullman car, and in 1895 it was replaced by 20-ton Engine No. 2. However, the depot, also completed in 1891 still stands at the corner of N. Oregon and C streets, although it has been turned 180 degrees. You know it as the Jacksonville Visitors Center and Chamber of Commerce. We’ll be sharing more RRVR history in the next few weeks.

Jacksonville Train Depot #2

From 1893 to 1915, the Jacksonville-to-Medford 5-mile spur Rogue River Valley Railroad was a “family affair.” In 1893, William S. Barnum leased the railroad from the RRV Railway Company, running the trains with the help of his 2 sons. His 14-year-old younger son, John Barnum, became the youngest train conductor in the nation! In the 1890s, you might have seen John, resplendent in his uniform, standing at the Jacksonville train depot at the Corner of N. Oregon and “C” streets. In 1899, William Barnum bought the railroad for about $12,000. Nine years later he added a gasoline motor car and 3 freight cars. In 1915, the family sold the RRVRR to the Southern Oregon Traction Company for $125,000—part cash, part mortgage.

Jacksonville Train Depot #3

According to “old timers,” this 5-mile spur not only served as a railroad; it also became a “school bus.” Dates are unclear—it may have been around 1903 when the 2nd Jacksonville school burned; or around 1906 when the 3rd Jacksonville school burned; or it may have been because the Medford schools offered curriculum not available in Jacksonville; or it may have been during World War 1. Pick your time frame! Regardless of the date, we know the spur railroad ran a block away from Medford’s Washington School, constructed in 1896 on the site of the current Jackson County Courthouse. Kids could ride the train for 5 cents. And naturally kids would be kids. They would periodically put lard and grease on the train rails, causing the train wheels to spin. The conductor soon realized he had to carry a bucket of sand. When the train rails spun, he would jump off and sand the track.

Jacksonville Train Depot #4

The Rogue River Valley Railway’s first engine—Engine No. 1—was put into service in May of 1891 to haul gravel, bricks, timber, crops, livestock, mail and passengers over the 5-mile, single track spur line that connected Jacksonville with Medford. Nicknamed Dinky, the Peanut Roaster, the Tea Kettle, and the Jacksonville Cannon Ball because of its small size, Engine No. 1 soon proved too underpowered to haul the heavier freight loads up the 3% grade from Medford and was relegated to passenger service, pulling a single Pullman car. In 1895, the little 12-ton Porter engine was sold. It changed hands a number of times over the years until it was badly burned in a logging camp fire. In 1946, Helen O’Connor spotted the abandoned engine in Cottage Grove, OR, and bought it for her husband Chadwell, a steam engine enthusiast, inventor, and a Sci-Tech award and Oscar recipient from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The couple had Engine No. 1 rebuilt from the original Porter blueprints. Over the next 6 decades, the little engine saw new life as a private plaything, a Cottage Grove tourist promotion, transportation for families wanting to cut their own Christmas trees, and a “prop” in commercials and motion pictures until Mel and Brooke Ashland arranged for its purchase and restoration in 2014. Engine No. 1 now sits on original track on the Bigham Knoll Campus at the end of East E Street in Jacksonville.

Jacksonville’s 1856 Brunner building

Jacksonville’s 1856 Brunner building, at the corner of Main and South Oregon streets, is the oldest brick building in Oregon that’s still standing. Built as a dry goods store, it has at various times been a garage, a museum, and the town library.

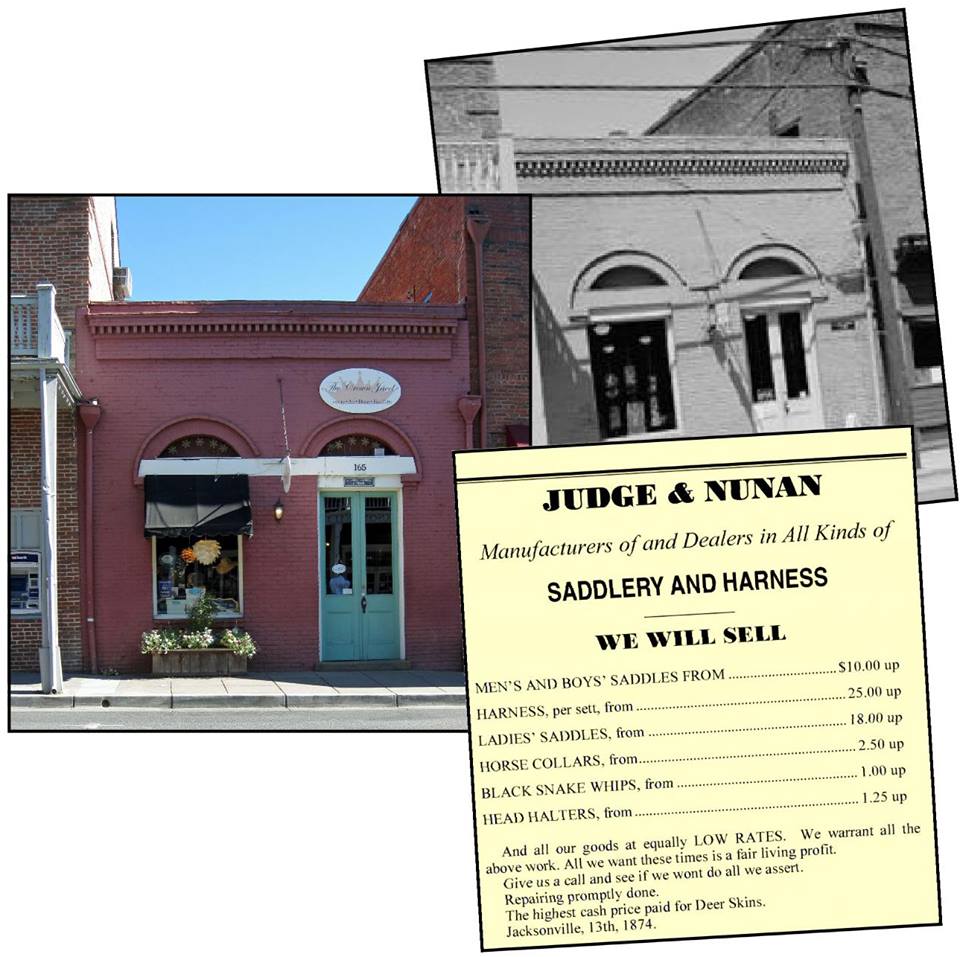

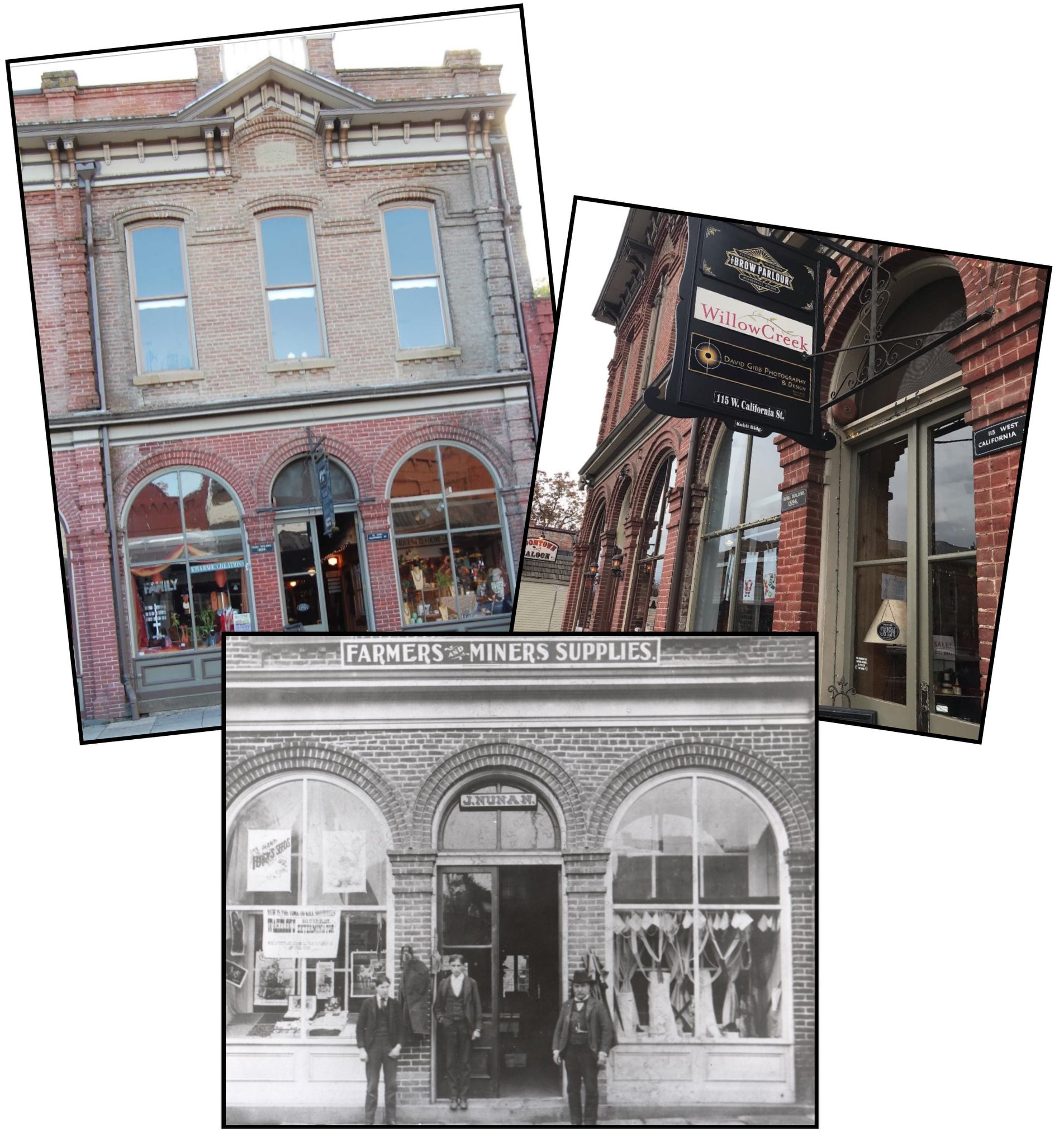

Judge & Nunan Saddlery

The small brick building at 166 E. California Street, tucked between the Jacksonville Inn and the U.S. Hotel, originally housed the H. Judge and Nunan Saddlery and Harness Shop. Constructed in 1874 following the disastrous fire that had wiped out the entire block the previous year, the building replaced Horne’s Hall, a 2-story building with rooms and offices below and “a steel sprung floor on the second floor expressly made for dancing.” One year later, Henry Judge, one of the town’s first trustees, broke his partnership with Nunan. Jeremiah Nunan continued to operate the business but by the early 1880s was dealing in general merchandise rather than saddles and harnesses.

Kahler Home & Drugstore

Although now a retail store, Jacksonville’s 120 West California Street address is one of the few town sites that once was used continuously for medical related purposes for 140 years!

As early as 1855, G.W. Greer, “physician and surgeon,” occupied an office at this site, part of an assemblage of shops fronting California Street and known as Kennedy’s Row. In 1862, L.S. Thompson had joined Greer in dispensing drugs and medicines. Thompson purchased this lot and a year later had a new wood frame building erected. By 1868, Sutton and Stearns were occupying the site, advertising “everything usually found in a first-class drug store.”

Three years later the “City Drug Store” was in the possession of Robb & Kahler. Robert Kahler was a member of a prominent Jacksonville family that came to Southern Oregon from Ohio in 1852. Kahler had become a successful druggist, selling not only drugs, but also books, stationery, paints, oils, and other goods. His brother, C.W., a prominent lawyer, bought the lot along with the property behind the Beekman Bank where he built his law office. The business became known as “Kahler & Brothers.” Robert had the current 1-story brick building constructed in 1880 at a cost of $2,000. The local press eagerly declared it to be part of Jacksonville’s “New Boom.”

As late as the 1980s the building was occupied by Dr. Griffin Osteopathic, the last medical related business to actually occupy the site. (Today you may more closely associate Griffin with Jacksonville’s “Doc Griffin Park.”) Although more recent owners have turned it into retail space, we should note they’ve also had close connections to the pharmaceutical industry.

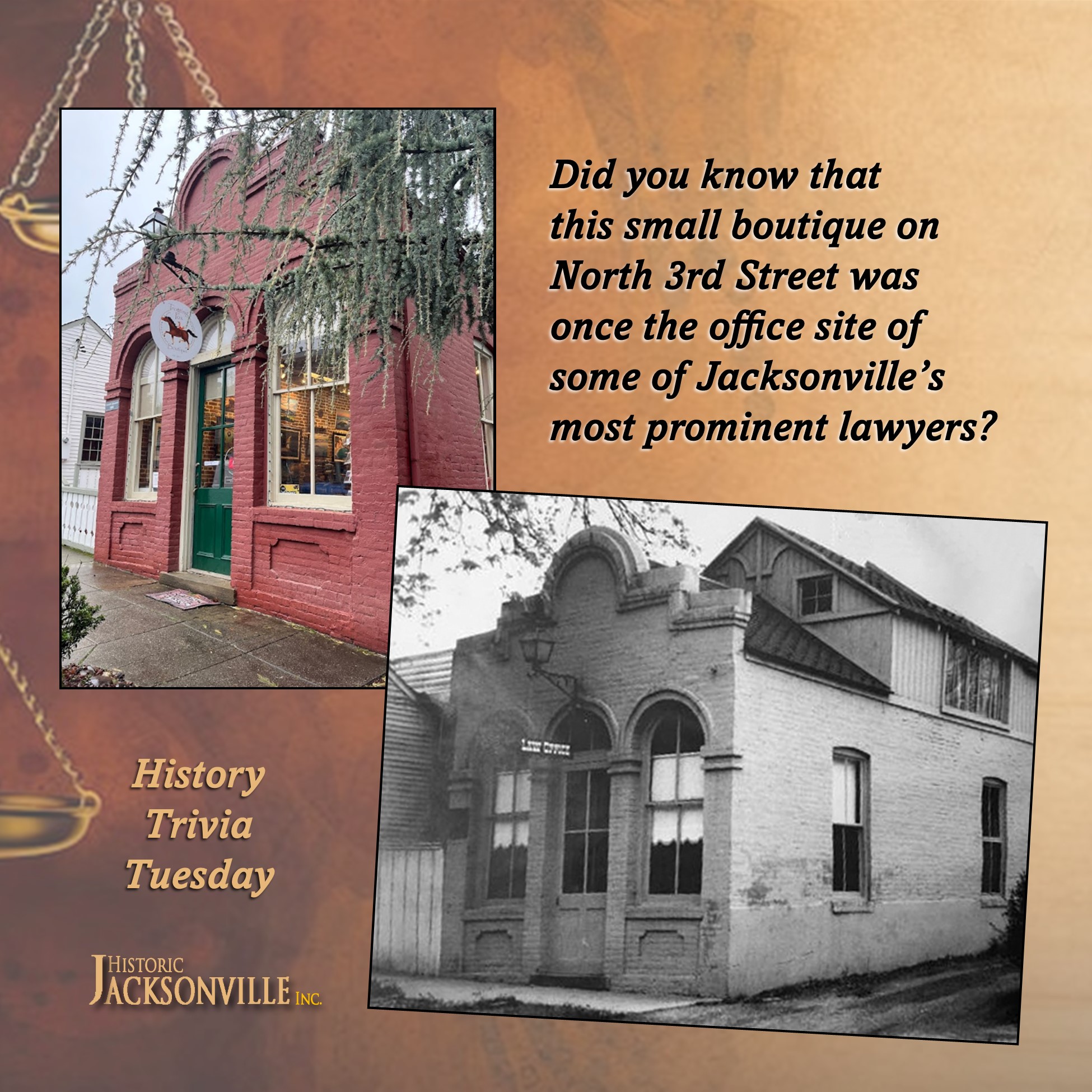

Kahler Office

Did you know that for many years, 155 North 3rd Street in Jacksonville was the site of law offices? By 1856, Paine Page Prim, Supreme Judge and ex-officio Circuit Judge of Jackson County’s 1st Judicial District, hung out his shingle here. Prim subsequently was elected to the Oregon Supreme Court and served on it for 21 years including 3 terms as Chief Justice.

In 1862, Joseph Gaston, lawyer and editor of the “Sentinel” took over the space. After leaving Jacksonville, he was a pioneer in Oregon’s railroad building efforts and for many years editor of the “Portland Oregonian.”

Prominent local lawyer Charles Wesley Kahler acquired the property in 1874, but it was 1877 before he and his partner, Edward B. Watson, moved their offices to the site. Watson also served as Jackson County Clerk prior to being elected in 1880 to the Oregon Supreme Court, becoming its 12th Chief Justice.

In 1886, Kahler erected the current brick building, replacing what was by then one of Jacksonville’s vintage wooden structures. Kahler was a long-term resident of Jacksonville, arriving with his parents at age 11. He became a prominent lawyer and District Attorney. He was fondly recalled as “a complete gentleman, always cordial and gracious.”

Karewski’s Grist Mill

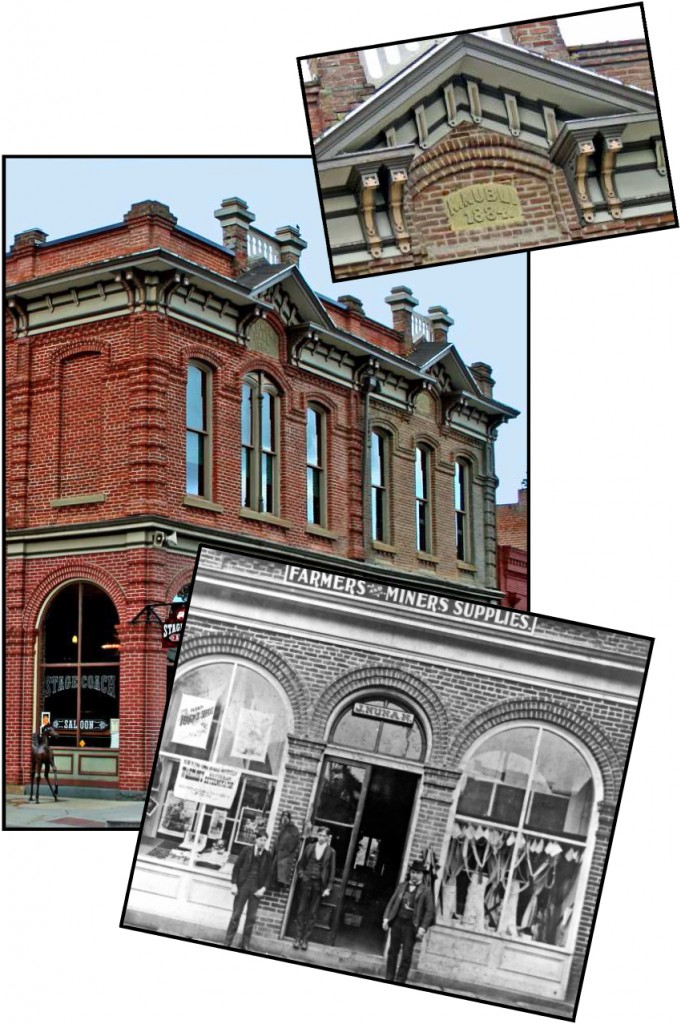

Kaspar Kubli Building

Adjoining Jacksonville’s Red Men’s Hall at the southwest corner of California and 3rd streets, and probably constructed by brick mason George Holt at the same time in 1884, is the almost identical Kaspar Kubli Building. The ground floor rear housed Kubli’s tin shop while the front was occupied by Jeremiah Nunan’s Farmers and Miners Supplies through the turn of the century. The site had originally hosted the first court ever convened in Jacksonville.

Kennedy’s Row – Carefree Buffalo Store

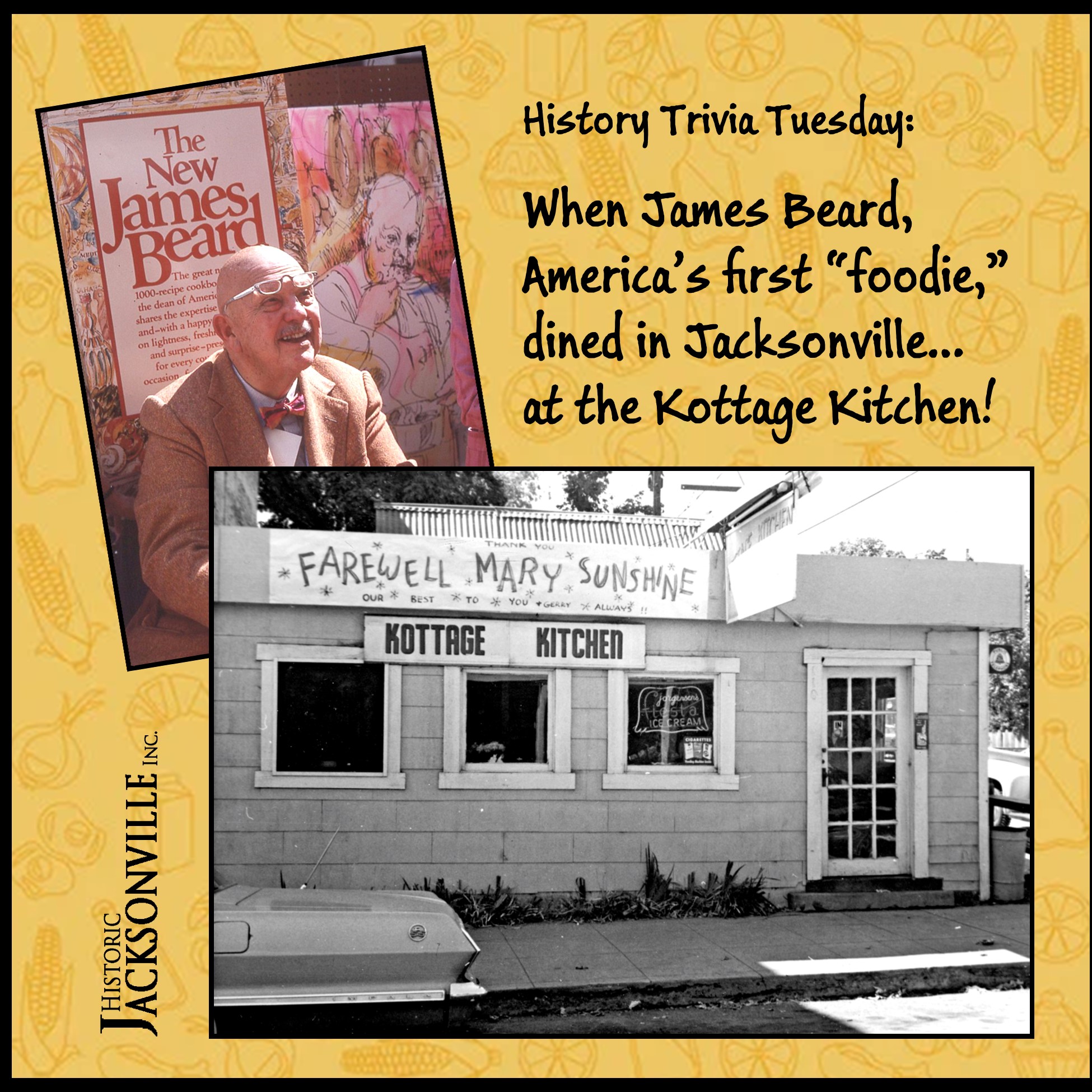

Kottage Kitchen

Did you know that James Beard, “America’s first foodie,” the leading U.S. culinary figure during his lifetime, and “The Dean of American Cuisine,” once dined in Jacksonville? And no, it was not at the Jacksonville Inn or one of the town’s other popular restaurants we’re familiar with today. This was during the 1960s and the “restaurant” was actually a small diner built around a circus wagon. It stood at the corner of California and 3rd streets where the replica of Beekman’s Express Office now houses Umi Sushi.

Called the Kottage Kitchen, it was owned and operated by Clifford and Mary Cowan. “Aunt Mary” was known for her good food, and the Kottage Kitchen was “the place to eat,” frequented by the likes of the sheriff and the mayor. Of course, it may also have been about the only “restaurant” in town….

James Beard dined there as the guest of Robbie Collins, the individual who was the key “mover and shaker” in preserving and restoring the town’s historic buildings and establishing Jacksonville’s “National Historic Landmark District.” Beard “loved” the Kottage Kitchen’s food and gave it a positive review, putting it “on the map.” [Collins later confided that Beard was quite drunk at the time.]

After Clifford died, Collins bought the corner lot and let Mary keep on cooking. When the Health Department showed up one day, intent on closing the Kottage Kitchen, Collins pleaded for one more year and then Mary could retire. The Health Department relented, and Mary operated her diner for another 12 months. When she retired, the entire town held a parade to honor “Mary Sunshine”!

Kubli Building

“What goes around comes around”! Where Willow Creek now sells jewelry, accessories, personal items, and an array of other indulgences at 115 West California Street in Jacksonville, J.S. Howard, the “Father of Medford” originally enticed customers with the merchandise in his “Crystal Bazaar.” When the building and all its contents were destroyed in the 1884 fire, Howard “abandoned shop” and moved to Medford, selling the lot to Kaspar Kubli. Swiss immigrant Kubli, who had found success in ranching, business, and politics, had the current structure erected at the same time as the adjacent Red Men’s Hall. Probably built by brick mason George Holt, the two buildings have almost identical facades. Originally, Kubli housed his tin shop in the ground floor rear. The front was occupied by Jeremiah Nunan’s Farmers and Miners Supplies through the turn of the century.

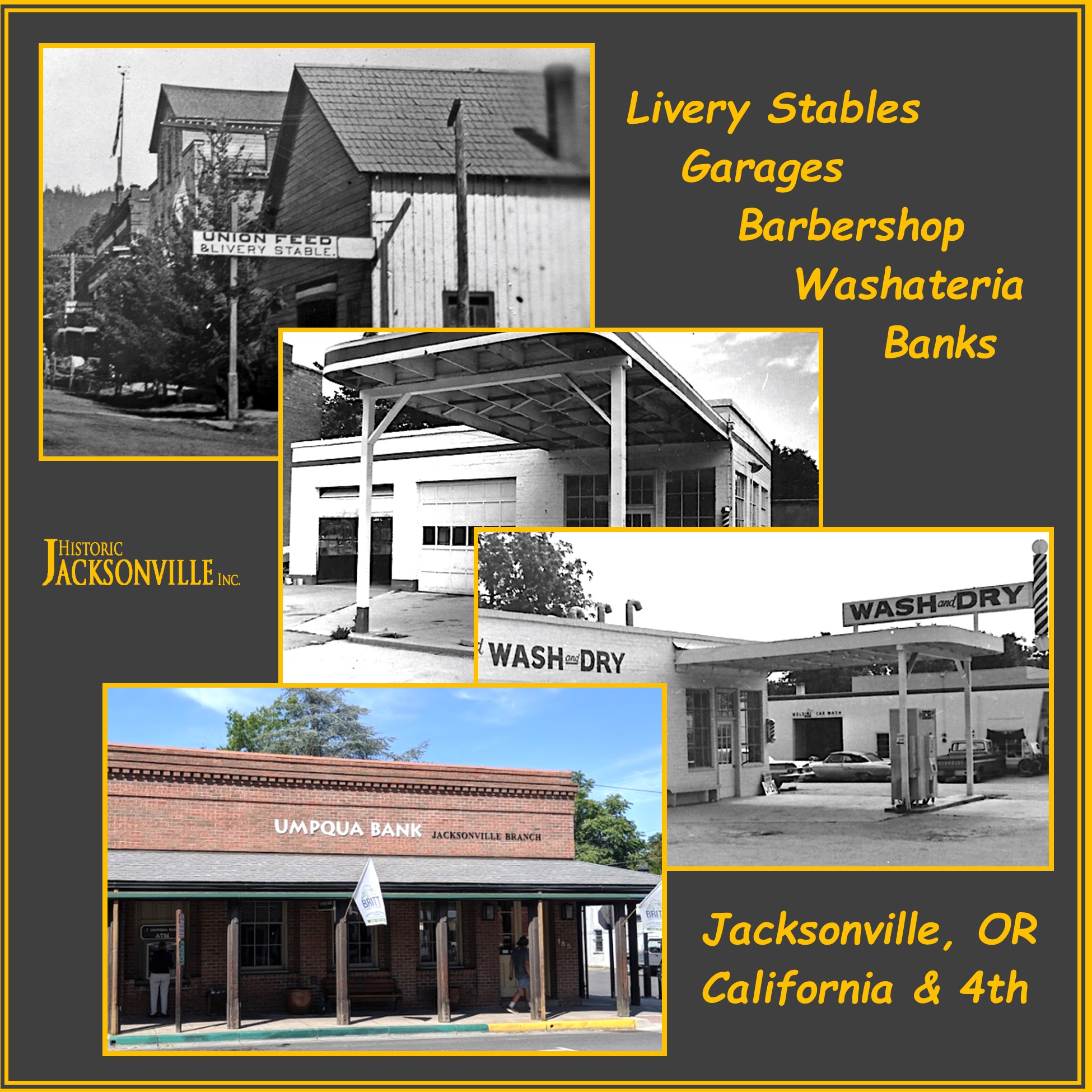

Livery Stable

From the mid-1850s until at least 1907, it was the site of the Union Livery Stable. Horses, saddles, wagons, buggies, and tack could be rented as needed, and drivers could be provided. Carriages for residents were stored there and horses stabled. In 1911, the Union was replaced by the Bailey Livery Stable. Before long, however, “horseless carriages” replaced horses and a Mobil gas station replaced the old livery stable. It operated at this corner for a number of years, but by the 1950s there were FOUR gas stations in Jacksonville! The Mobil station went out of business, and for a short time the building was occupied by a barber shop. However, there were still 3 gas stations in town. We’re not sure how many people had cars, but with lots of folks not having washing machines, what was needed was a laundromat. Enter the Wash and Dry washateria. It lasted until about 1970. In 1972, the Jackson County Federal Savings & Loan took over the site, erecting a new building. Founded in 1909, JCF S&L became part of Key Bank in 1993, which was subsequently acquired by Umpqua in 2014. Whew!

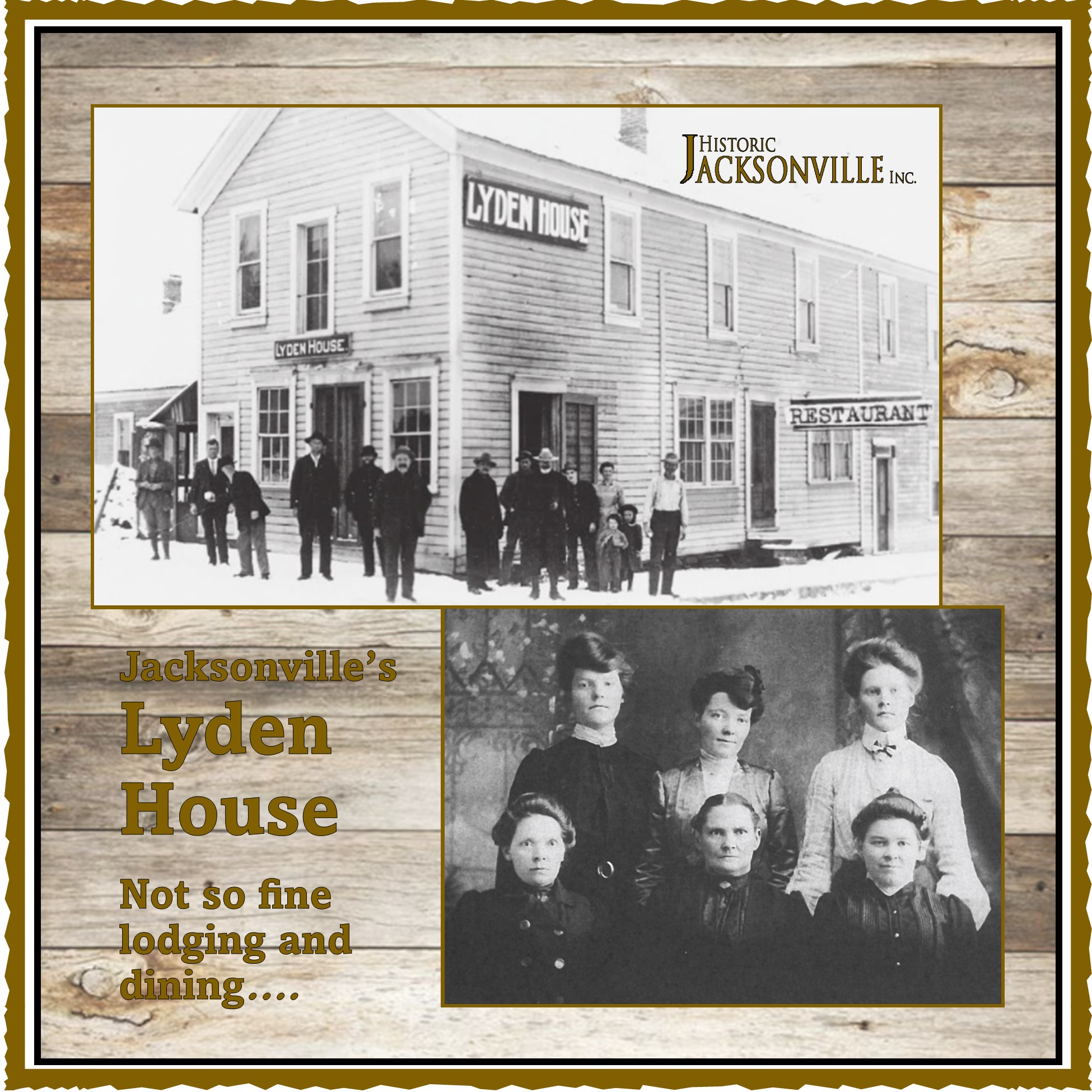

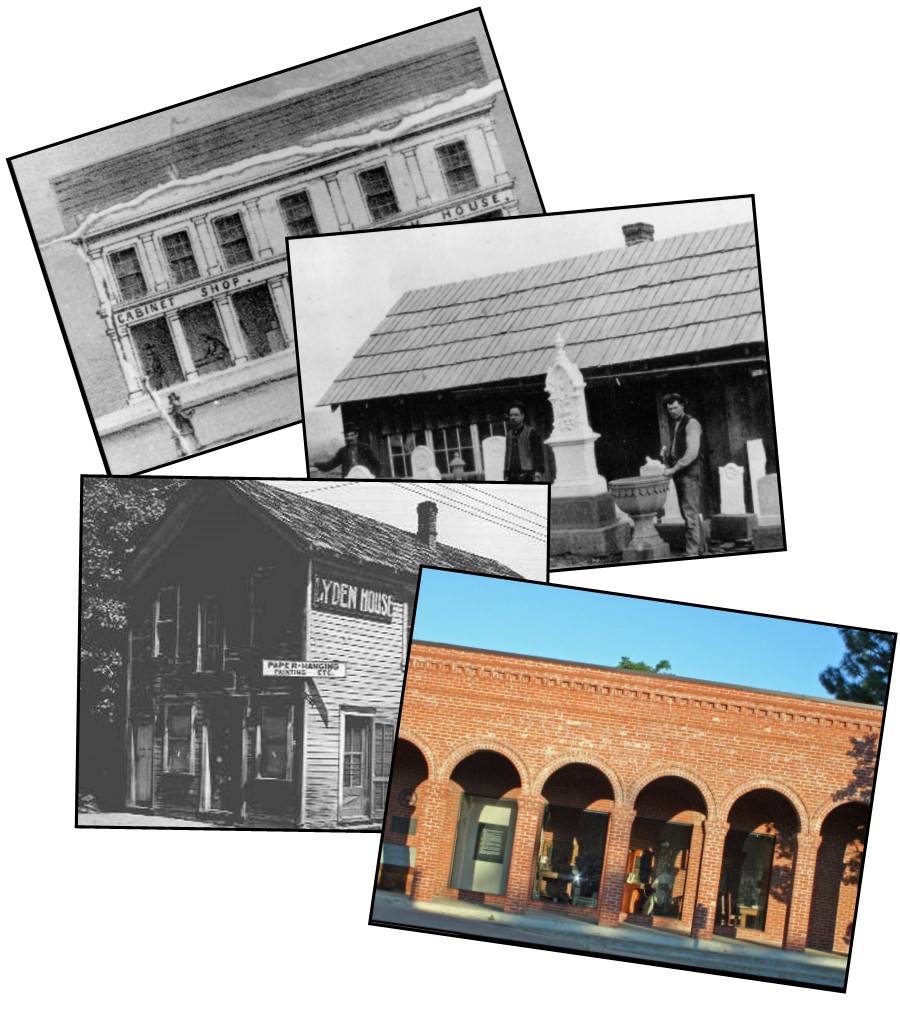

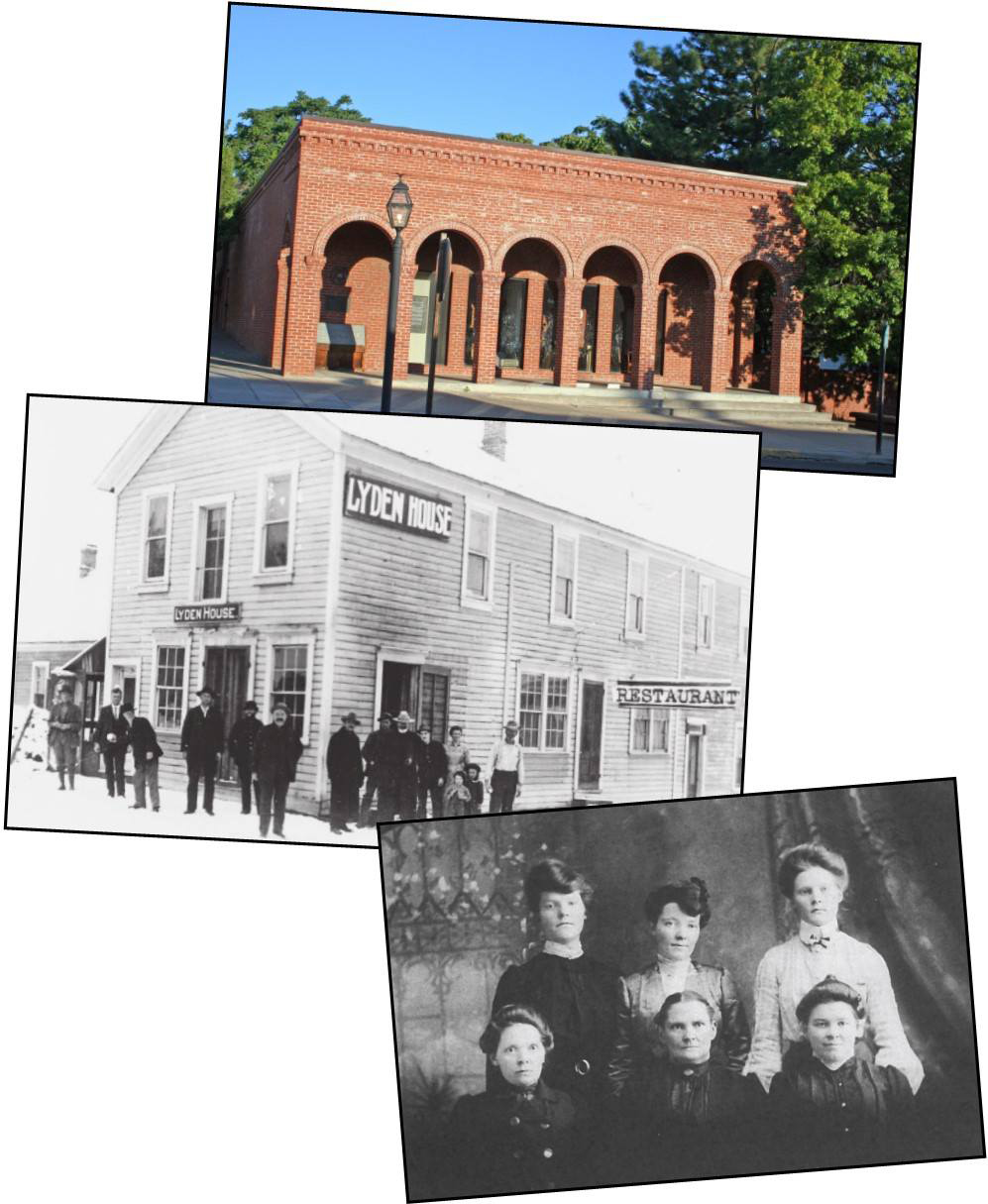

Lyden House

Jacksonville’s California and Oregon street corner, the current site of the telephone exchange building, was previously home to the Lyden House. When J.C. Whipp moved his Marble Works to Ashland in 1902, Michigan native John Lyden converted the old showroom into a boarding house. John and his wife Mary ran it for the next few years, charging 35 cents for a night’s lodging in one of its 11 rooms. Rooms were furnished with washstands, a pitcher, a wash bowl, a chamber pot commode, a “well supplied” towel rack, and an iron bedstead with ample bedding. The hotel was usually full by nightfall.

About 1903, Mary Lyden and her daughters, Helen and Anna (Nan), started the “Hooligan Restaurant.” It became famous for its “good homey table” and “wonderful filling meals,” served for 65 cents. Special dinners could also be ordered. The enterprising Lydens also carried a good supply of items such as pots, pans, canteens, and other tinware in demand by miners and prospectors still hoping to strike it rich in the hills around Jacksonville.

However, Helen married J.B. Abernathy and move to Detroit, Michigan. Mary died in early 1907, and Nan married Christ Kenney later that year. Although Nan may have continued to help her father, the Lyden House became what might best be described as a “flea bag” hotel. But it did offer “guests” a good supply of “Buhac” to discourage unwanted bedfellows.

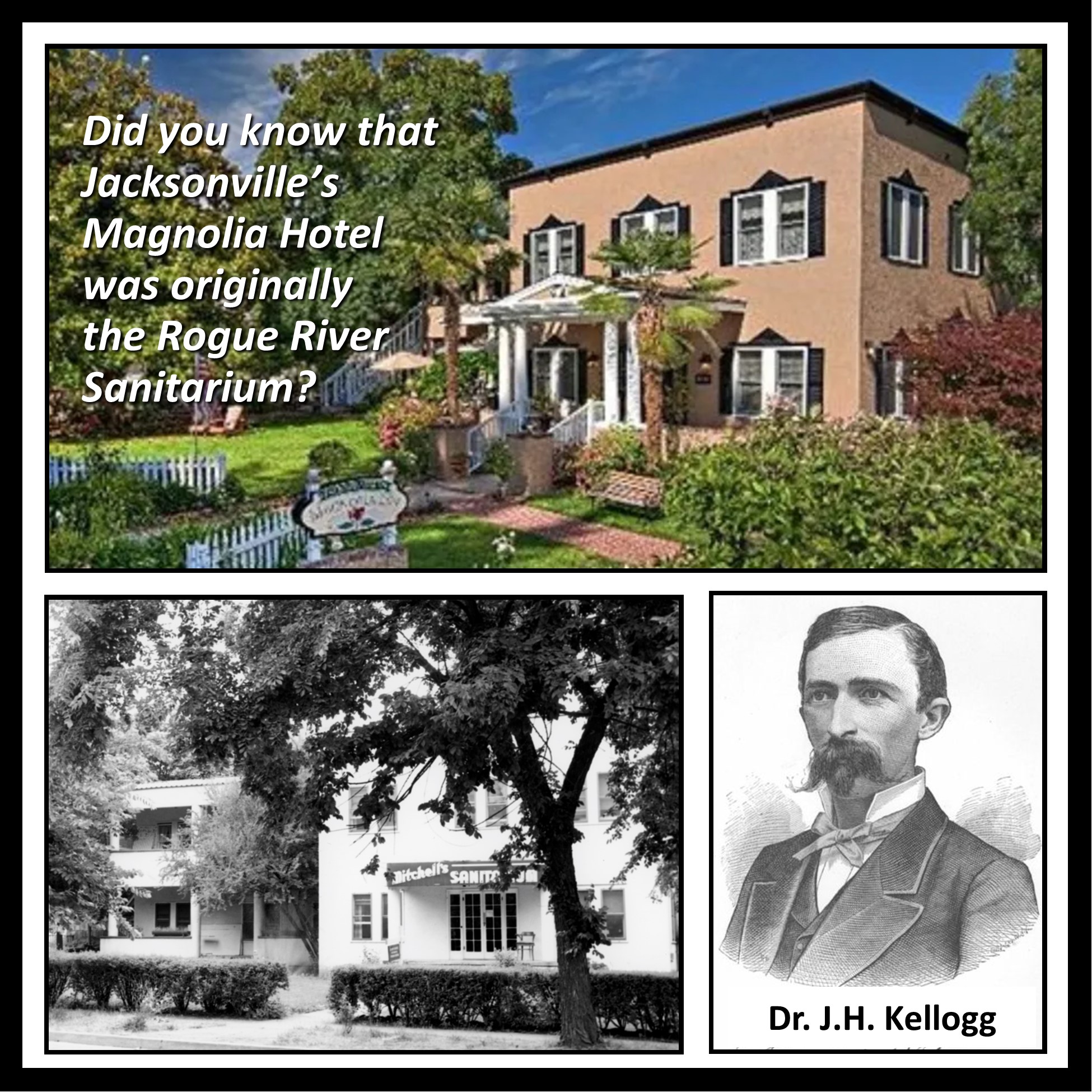

Did you know that the Magnolia Hotel at 245 North 5th Street in Jacksonville was built in the early 1900s as the Rogue River Sanitarium? At the time, that meant health spa. Such sanitariums were part of the “Wellville” movement pioneered by the Kellogg brothers. This approach to medicine advocated holistic treatments and vegetarianism, and such sanitariums typically focused on nutrition, exercise, and…enemas to cleanse the system. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg also created the “health food,” Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, in hopes that it would reduce what he considered unwelcome sexual impulses.

However, by the time this Spanish Revival style structure was built, Jacksonville had lost its status as the hub of Southern Oregon. The railroad had by-passed the town, and soon the county seat would be moved to Medford. When the great Depression of the 1930s hit, Jacksonville’s population was only 700 and most buildings stood empty. Jackson County began placing most of its poor in Jacksonville’s empty buildings because property values were some of the lowest in the County and there were plenty of potential caretakers among the people looking for work. The Rogue River Sanitarium was one of these “poor houses,” but it was as much hospital as sanitarium.

In the early 1950s it was purchased by Bessie Mitchell and rechristened the Mitchell Sanitarium. Bessie was a young widow with several children, two of whom were disabled and needed full-time care. Her only training had been in nursing, and the sanitarium allowed her to care for her children while securing income to support her family. According to a daughter, Bessie was an enterprising woman and had negotiated the purchase without a cent in her pocket. The sanitarium became a family operation and what a long-time resident described as a “senior guest house.”

It was converted into a bed and breakfast inn in 2007. Current owners envision tapping into some of the building’s earlier “vibe” as a place for healthy activities and retreats—but without the enemas and cornflakes!

Miller Gunsmith Shop

The historic marker on the building at 155 W. California Street in Jacksonville reads “Miller Gunsmith Shop circa 1858.” It’s half correct. The current structure did house John F. Miller’s Hunters’ Emporium, which specialized in guns, and later hardware and cutlery, for at least 20 years. However, this commercial Italianate-style structure was not built until 1874. As early as 1852, the property was originally part of Jacksonville’s most notorious “temple of vice,” the El Dorado Saloon, home to gamblers, courtesans, and others seeking to part miners from their gold. Miller acquired the property after the disastrous fire of 1874 which destroyed most of the original buildings on this block. A native of Bavaria, Miller had arrived in Oregon in 1860 and became one of Jacksonville’s most prosperous early business owners.

Orange Jacobs Law Offices

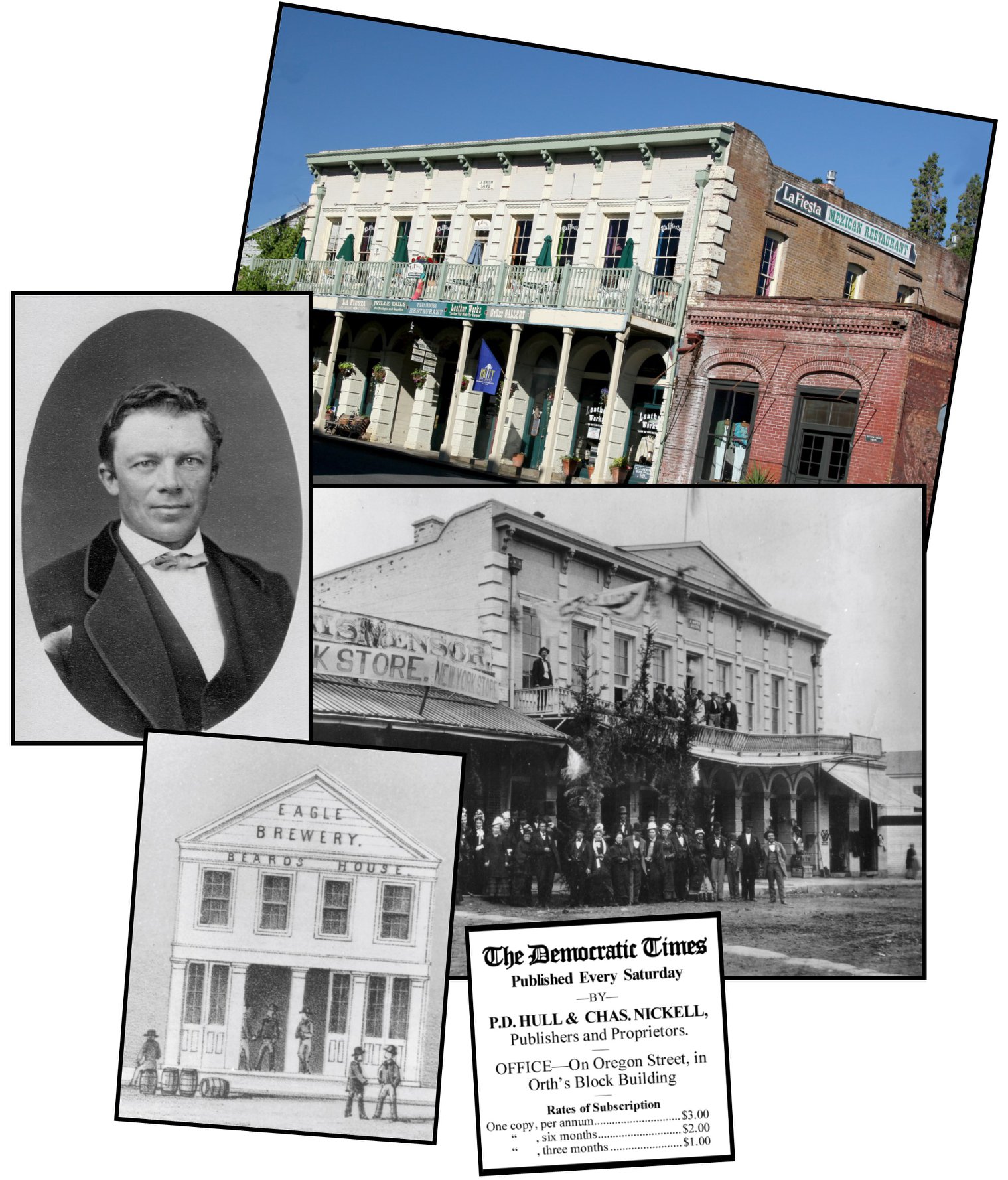

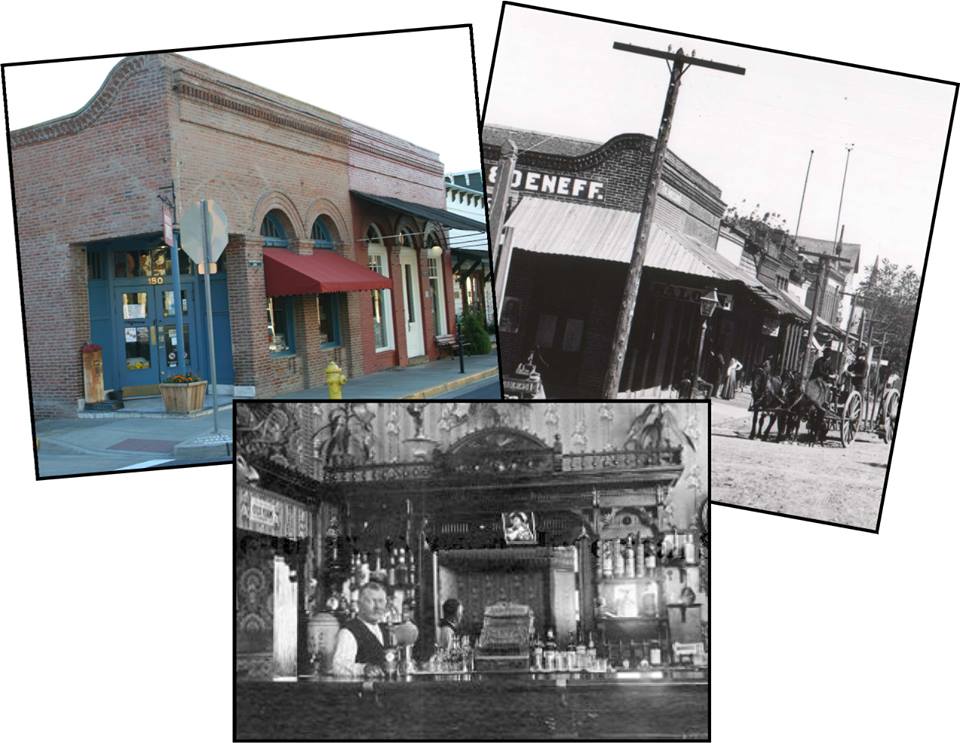

Orth Building #1

The 2-story Orth building, located at 150 S. Oregon Street in Jacksonville, was erected in 1872 by German born butcher, John Orth. Prior to the building’s construction, Orth’s butcher shop had occupied a wooden frame building on the same site, sharing the block with the Palmetto Bowling Saloon, the Old City Brewery, and the City Drug Store which served as both pharmacy and hospital. When Orth razed the older buildings to make way for his new edifice, the Democratic Times newspaper noted that the site had been “devoted to almost every purpose except printing a newspaper and serving God.” The Democratic Times rectified one omission, taking office space in Orth’s new brick building.

Orth Building #2

The 2-story Orth building, located at 150 S. Oregon Street in Jacksonville, was erected in 1872 by German born butcher, John Orth. Prior to the building’s construction, Orth’s butcher shop had occupied a wooden frame building on the same site, sharing the block with the Palmetto Bowling Saloon, the Beard House and Eagle Brewery (later the Old City Brewery), and “an old hospital building.” When Orth razed the older buildings to make way for his new edifice, the Democratic Times newspaper noted that the site had been “devoted to almost every purpose except printing a newspaper and serving God.” The Democratic Times rectified one omission, taking office space in Orth’s new brick building.

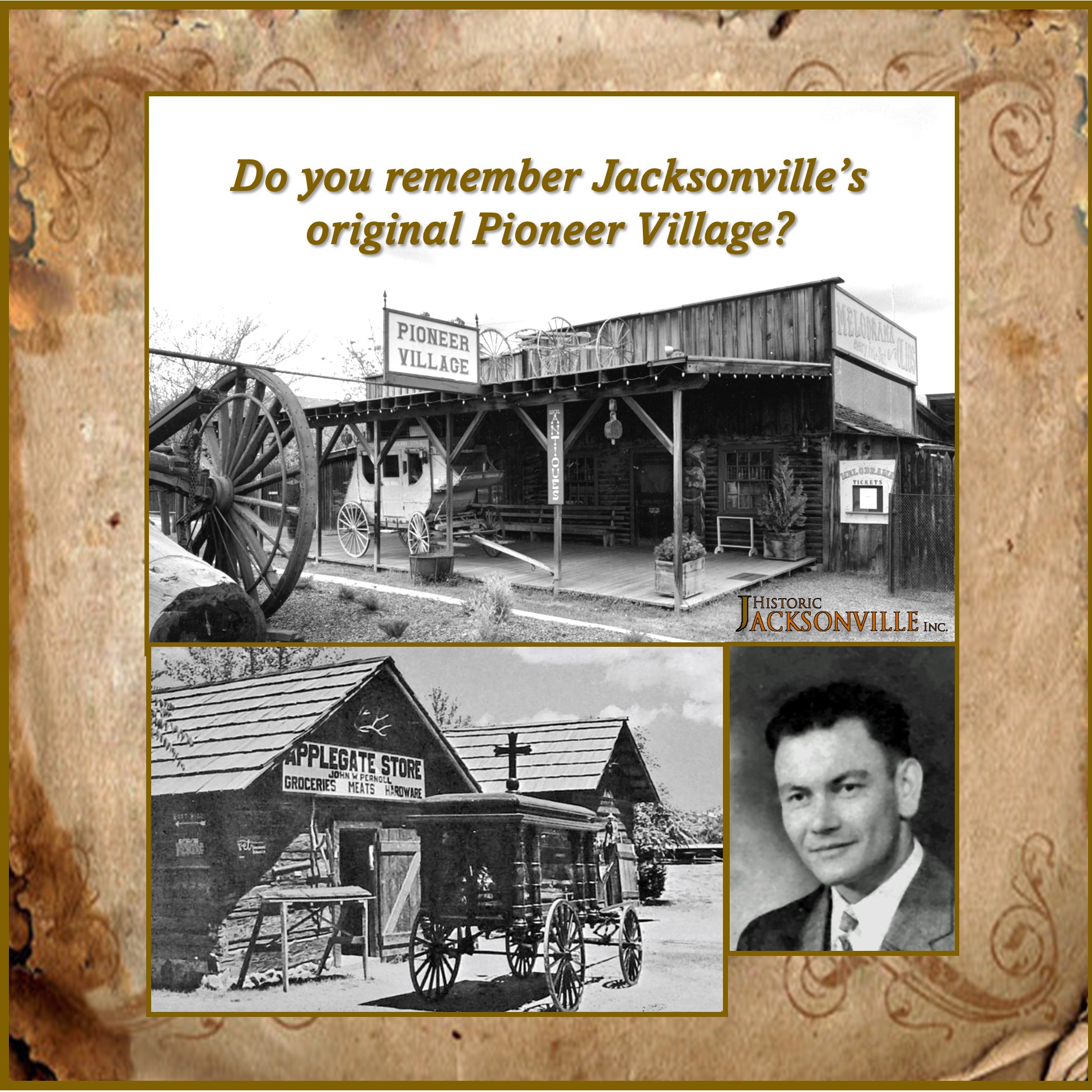

Pioneer Village

Jacksonville’s current Pioneer Village at 805 North 5th Street is the namesake of an earlier 5-acre Pioneer Village constructed by George McUne between 1961 and 1964. For over 20 years, McUne’s Pioneer Village was an adventure into Jacksonville’s past with authentic buildings from nearby locations that were filled with the historic relics McUne collected. In the village stockade, visitors watched western fights and “black snake whip” demonstrations. They took pony rides and boarded a stagecoach. They watched a blacksmith make hand rolled wagon wheels in his forge. They enjoyed Victorian melodramas. They explored Yreka’s Dogtown Saloon, still sporting bullet holes in the front door; or visited a jail, a moon-shiner’s cabin, or a little red schoolhouse that served Valley Falls students in southeast Oregon from 1880-1919. When George died in 1979, his passion for historical treasure died with him. His collection of 8,000 items was sold in 1985, leaving an empty lot that would later become the Pioneer Village Retirement Community.

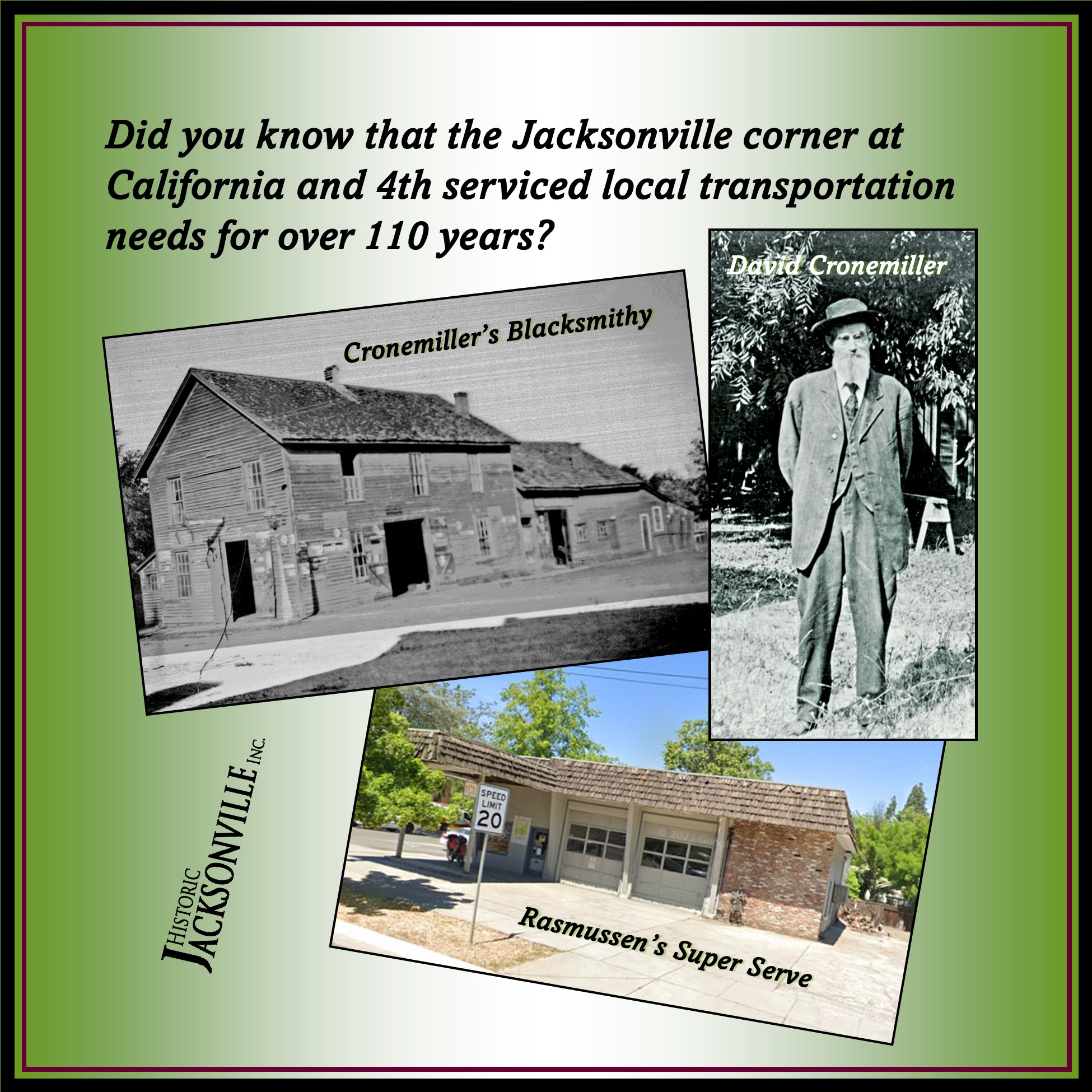

Rasmussen’s Super Serve

Did you know that Jacksonville’s northeast corner of California and 4th streets housed businesses serving local transportation needs for over 110 years? Most residents associate the location with Rasmussen’s Super Serve. Established by Ernest Rasmussen in 1950 as a combination gas station and car repair shop, the gas station portion closed long ago, but Ernest’s grandson Steve still operated the popular local repair service until 2022. However, that corner has an even older history of servicing local transportation.

David Cronemiller, a native of Pennsylvania, arrived in Jacksonville in the early 1860s, and opened a blacksmith shop on that site in competition with the successful Patrick Donegan smithy diagonally across California Street. Business must have been booming since Cronemiller’s original smithy was soon replaced by a large, well-equipped blacksmith and wagon shop. He was described as “an excellent mechanic,” “always kept busy by satisfied patrons.”

Donegan had closed shop by the late 1800s but Cronemiller continued to operate successfully until 1904 when his health began to fail. Cronemiller died in 1910, mourned by many for both his “honest and upright” nature and “his gentle forbearing ways.”

Cronemiller’s smithy and wagon shop were torn down in 1929.

Rogue River Electric Company #1

The Alaska Gold Rush brought electricity to the Rogue River Valley. When prospective Alaskan gold mines did not pan out for Dr. Charles Ray in 1900, he checked out Southern Oregon and purchased the Braden mine in Gold Hill. But to make it productive, it needed electricity. He began construction of the Gold Ray log “crib” dam in 1902, discovering in the process that electricity was more valuable than gold. By 1907, the Rogue River Electric Company supplied power not only to numerous gold mines in the region, but also to the cities of Medford, Jacksonville, Central Point, Grants Pass, Rogue River, and Gold Hill. The transmission line to the small one-story brick building at 225 W. California Street in Jacksonville was completed in 1905, and the building remained in service as an electricity substation until 1940.

Rogue River Electric Company #2

The Charles R. Ray Electric Substation at 225 E. California Street is located on an historic parcel of land that once was part of Jacksonville’s Main Street. The original wooden buildings subsequently became Jacksonville’s Chinatown, the oldest Chinatown in Oregon. Although the Chinese were greatly discriminated against and denied property rites, this site was conveyed to Lin Chow in 1859 and later to Leong Chow in 1872. In 1888, a fire originating n David Linn’s furniture factory across the street destroyed the entire block. The lot sat vacant until 1905 when the present brick building was constructed as the substation that brought electricity to Jacksonville.

Rogue River Valley Railway

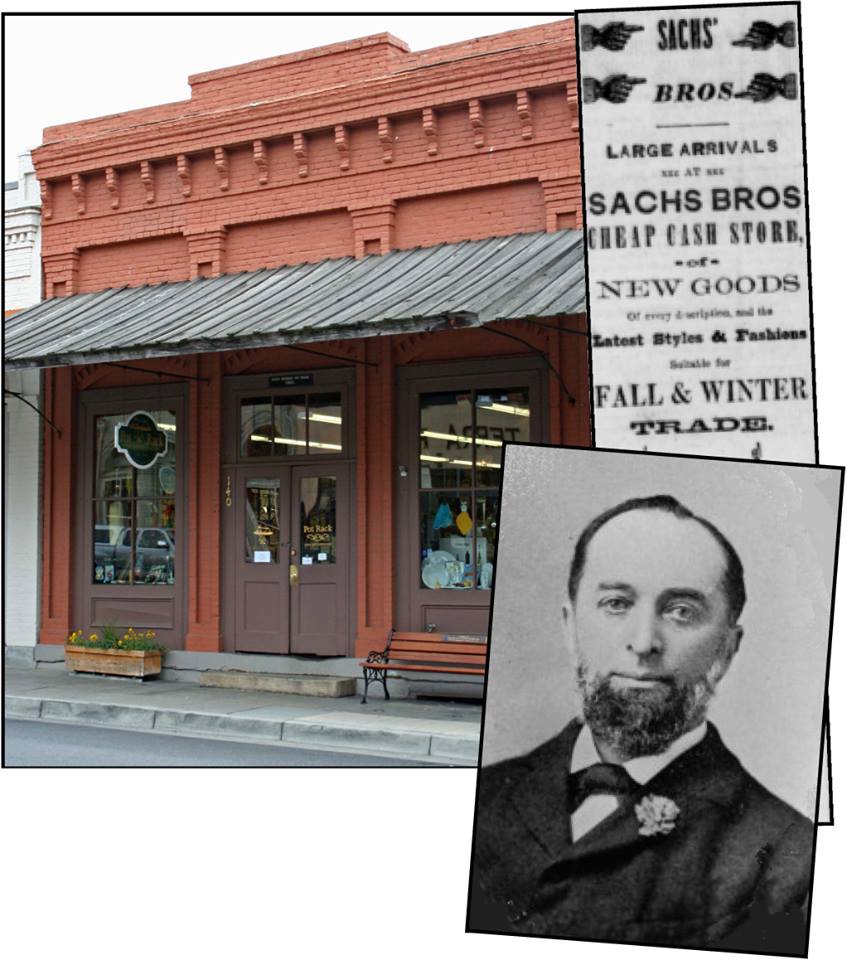

Sachs Brothers Dry Goods

The brick building now housing Jacksonville’s Pot Rack at 140 West California Street is historically known as Sachs Brothers Dry Goods. However, the site first housed Mathew Kennedy’s tin shop and then Dr. Louis Ganung’s office and residence. The current brick structure was commissioned in 1861 by Lippman and Solomon Sachs for their Temple of Fashion, featuring ladies’ wear and dry goods. It was one of the town’s most successful early businesses, and Sachs brothers ran it for the next 15 years.

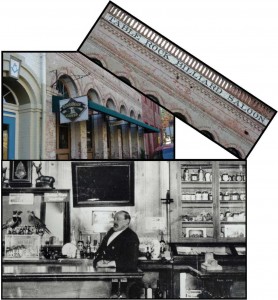

Saloons

|

|

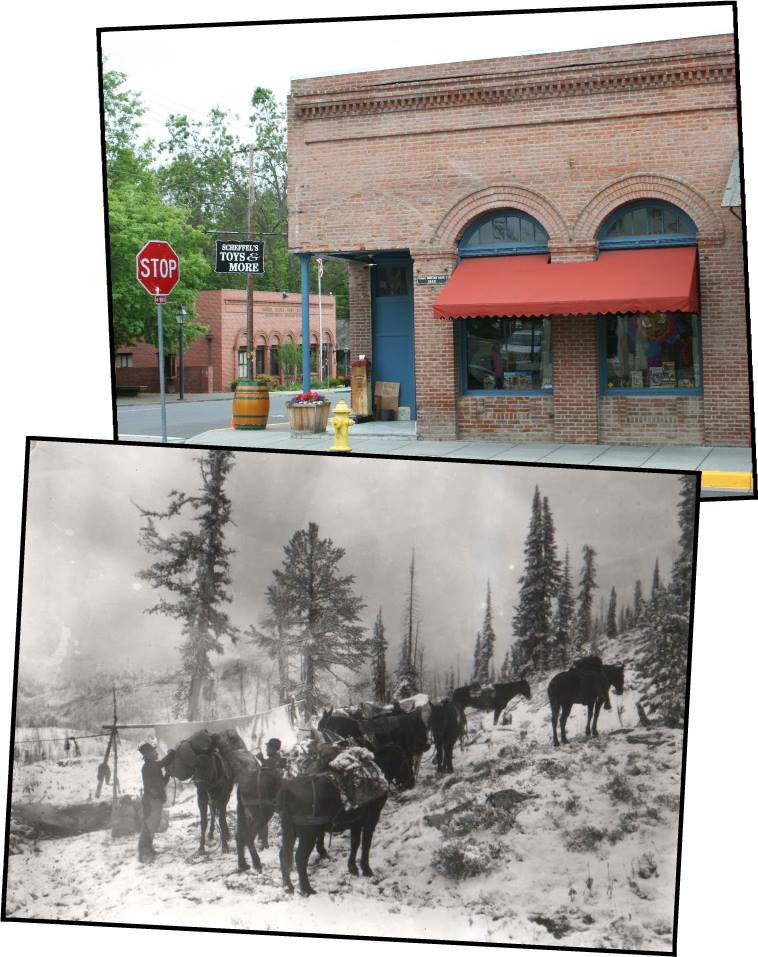

Scheffel’s Toys #1

The corner of California and Oregon streets where Scheffel’s Toys is located is the oldest known business site in Jacksonville. Early in 1852, soon after news of the gold discovery in Jacksonville spread to California, Kenny and Appler, two packers from Yreka, established the first trading post on this site. They stocked it with a few tools, clothing, boots, “black strap” tobacco, and a liberal supply of whiskey, essential items for an infant gold mining camp.

Scheffel’s Toys #2

The brick building at the corner of California and Oregon streets that houses Scheffel’s Toys is the 6th structure at this location. The site was originally home to Kenny & Appler’s 1852 tent trading post, the first business in Jacksonville. By 1856, their tent had been replaced by a wooden store and then by a brick storehouse. In 1860, merchants Abraham and Newman Fisher acquired this prime corner location for their dry goods and general merchandise store. Fires consumed their stores in both 1868 and 1874. Despite a $28,000 loss in the latter conflagration, the Fisher brothers rebuilt, and the 1874 A. Fisher & Brothers structure still stands today.

Scheffel’s Toys #3

The 1874 Jacksonville brick building at the corner of California and Oregon streets that houses Scheffel’s Toys is historically known as the Fisher Brothers Store, but one of its longest tenants was the Marble Corner Saloon also known as the Marble Arch Saloon. The saloon occupied the building from around 1890 to 1934. The saloon was presumably named after the Jacksonville Marble Works which relocated to the corner directly across North Oregon after the fire of 1888…or because the saloon’s recessed entryway was tiled with marble at roughly the same time. The 1912 SOHS photo #1978.63.53 shows Ed Dunnington behind the Marble Saloon bar.

South Stage Cellars

South Stage Cellars, at 125 South 3rd Street in Jacksonville, has had many incarnations. Built around 1865 by Irish immigrant P.J. Ryan as his residence, it subsequently housed hotels, a restaurant, a doctor’s office, a butcher shop, an ice cream parlor, and a saloon. In the 1960s it became the home of Robertson Collins, the individual credited with preventing Highway 238 from taking out 11 of Jacksonville’s historical homes and the leader of the organization that established the city’s National Historic Landmark status.

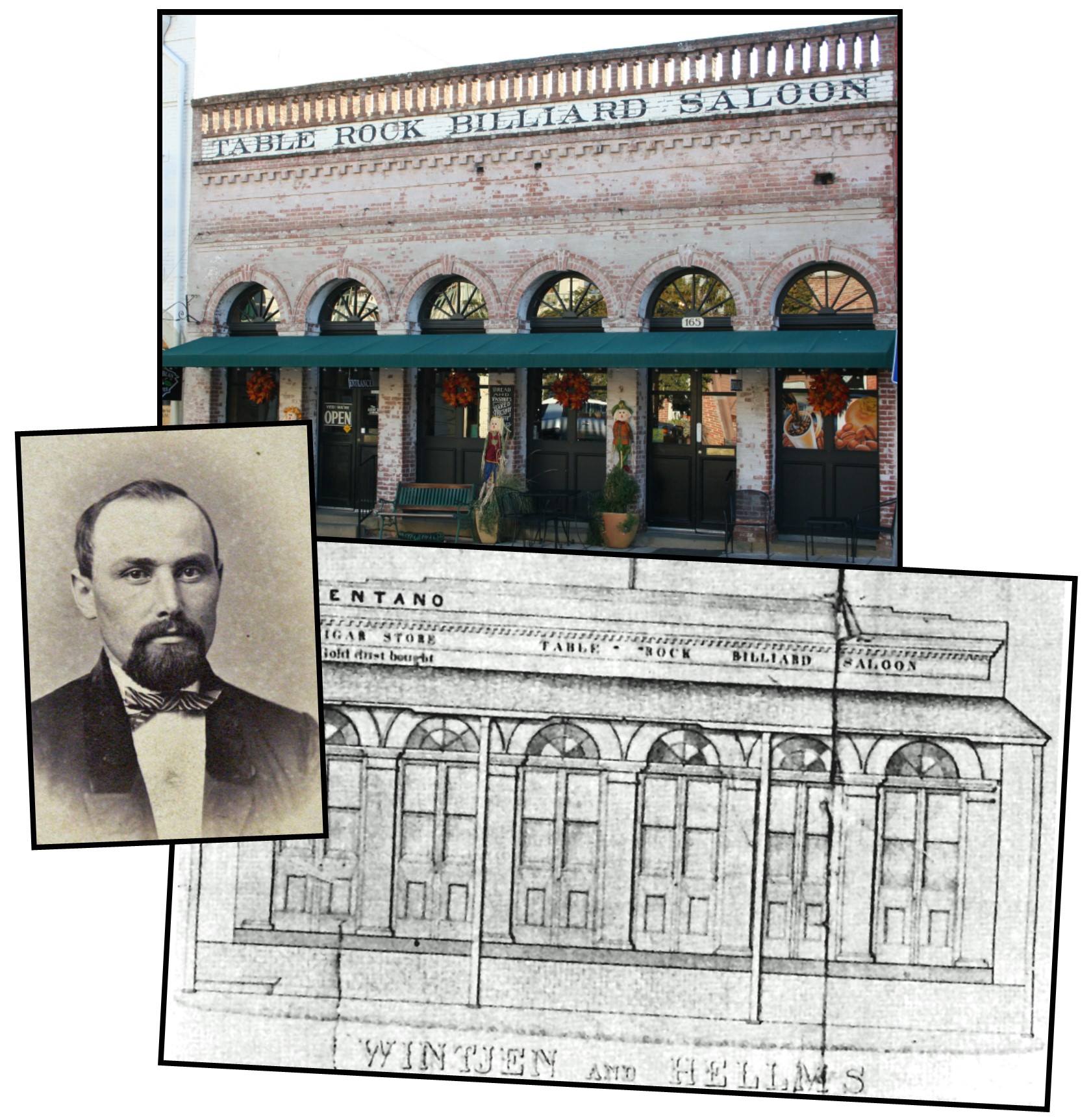

Table Rock Billiard Saloon #1

The Table Rock Billiard Saloon, constructed in 1860, was also Jacksonville’s first museum. Saloonkeeper Herman Von Helms collected fossils and oddities to attract a clientele that then stayed for his lager. For many years the saloon also functioned as an informal social and political headquarters, home to business deals, court decisions, and even trials. Fire gutted the building in 1960, leaving only the façade. The restored structure now houses the Good Bean Coffee House.

Table Rock Billiard Saloon #2

The building at 155-165 S. Oregon Street in Jacksonville that now houses Good Bean Coffee was built in 1860 by German immigrants Herman von Helms and John Wintjen, partners in the “Table Rock Bakery.” This Italianate brick structure replaced their earlier wood frame bakery that also provided space for a butcher shop, groceries, and supplies. Helms and Wintjen may have operated their bakery into the mid-1870s. As entrepreneurs, it’s quite likely they became saloonkeepers after the 1874 fire destroyed all the adjacent wooden buildings, including the notorious El Dorado saloon, a Jacksonville “institution” as early as 1852. The “Table Rock Billiard Saloon” sign was painted on the building in the early 1880s by which time Wintjen had retired. The saloon became an informal social and political headquarters, home to business deals, court decisions, and even trials. It was also Jacksonville’s first museum, “The Cabinet” – a collection of pioneer relics, fossils and oddities designed to attract a clientele that stayed for the saloon’s lager. Herman von Helms ran the saloon until his death in 1899. His son Ed operated it until his retirement in 1914.

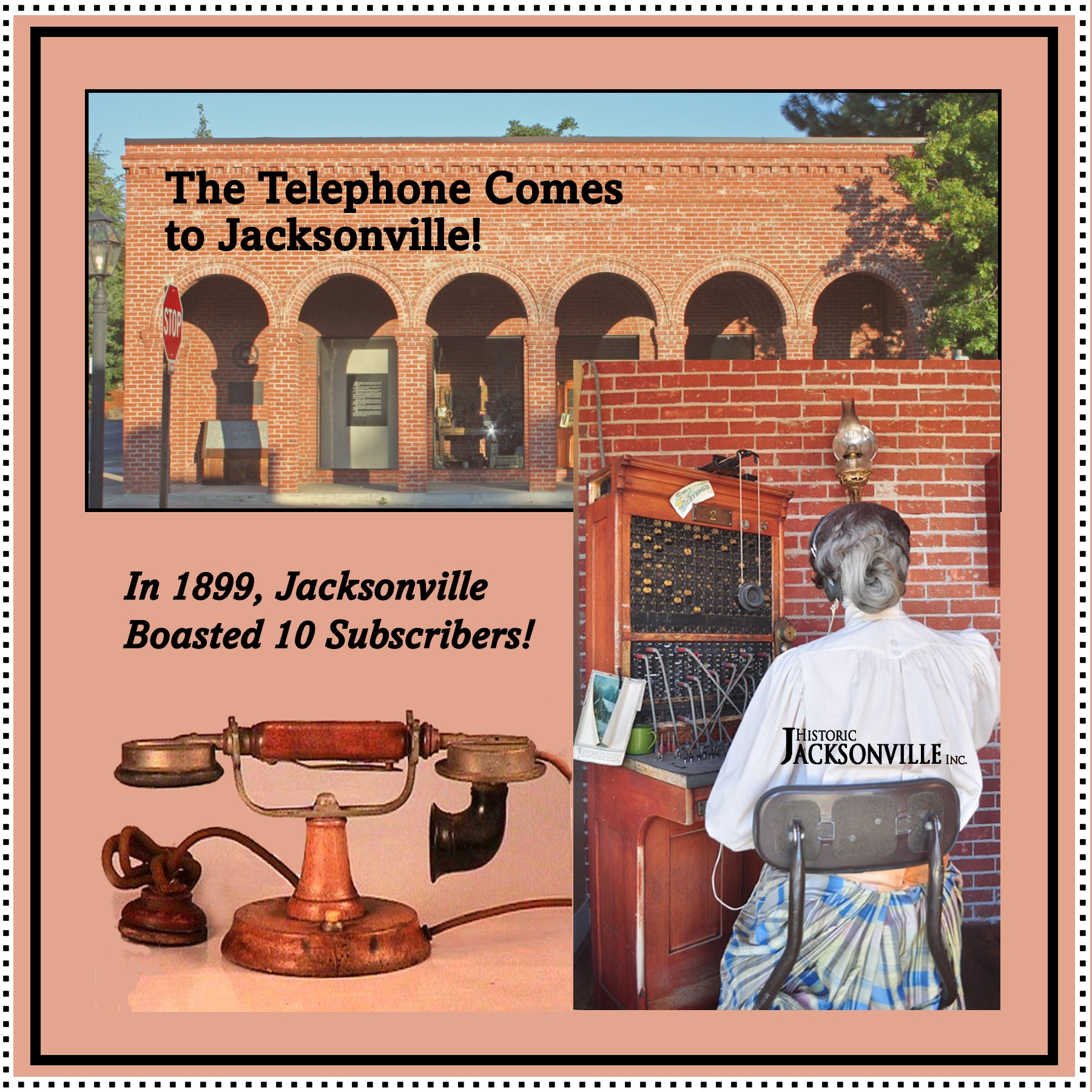

Telephone Exchange

Everyone’s necessary accessory, the cell phone, represents a huge leap from the beginning of Jacksonville’s telephone service. The plaque and display windows on the telephone exchange building at the northwest corner of California and Oregon streets tell only part of the story of the telephone coming to Jacksonville.

After Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the first U.S. patent for the telephone in 1876, demand for this novel invention spread. Initially, pairs of telephones were connected directly with each other. In 1888, Jacksonville’s first telephone line connected the U.S. Hotel with the Riddle House in Medford. However, it appears to have been short-lived due to costs.

Six years later, a syndicate installed a 2-point, 3-instrument Medford-Jacksonville line connecting the G. H. Haskins drug store in Medford with the county clerk’s office at Jacksonville’s County courthouse and the Reames, White & Co. store. A 5-minute talk cost 25 cents. By 1899, a regular telephone exchange serving 10 subscribers was established.

However, there was no direct dialing. In fact, there was no dial telephone—do you even remember the dial telephone? An operator switched connections between lines making it possible for subscribers to call each other at any location on the exchange. By 1918, service had at least doubled since Carrie Beekman was listed as #22 in the Jacksonville telephone directory.

The original telephone exchange was located in the small brick building at 255 E. California Street, more recently occupied by wine tasting rooms. The current California and Oregon street corner was originally home to David Linn’s furniture factory, showroom, and planing mill. When it burned in an 1888 arson fire, J.C. Whipp’s marble works took its place. Around the turn of the century, millwright John Lyden expanded Whipp’s display room into the Lyden House which became a popular boarding house and restaurant. A 1962 Mail Tribune wrote the Lyden House obituary when it was torn down and replaced by the current telephone exchange building.

Union Hotel

The southeast corner of Oregon and California streets has been the site of a hotel almost since Jacksonville was founded. As early as November 1852, Jesse Robinson claimed “squatters rights” to an existing 2-story wood frame structure. The “Robinson House” became a “private boarding house patronized by the elite.” Austin Badger and Nelson Smith purchased the building in late 1855, renamed it the Union Hotel, and enlarged it.

When Badger and Nelson couldn’t pay their debts, the Union Hotel was sold to Louis Horne who rechristened it the U.S. Hotel. Horne “improved” the hotel in 1868 by adding a 50’ x 30’ hall fronting on E. California. The 2nd floor, resting on “steel springs,” was made expressly for dancing; the ground floor housed offices and shops. Three years later a skating rink was opened in “Horne’s Hall.” The disastrous 1873 fire which leveled many of the wood frame structures on California Street was believed to have originated in a flue of the U.S. Hotel. The fire destroyed everything on the block…except for Horne’s chicken coop.

The property was subsequently sold at a sheriff’s sale and then resold to brick mason George Holt, and his wife, hotel proprietress Jeanne DeRoboam Holt. George fired the bricks for his wife’s long dreamed-of, brick hotel. The brick U.S. Hotel, the structure we know today, opened in 1880 with a Tammany Day celebration, a Fourth of July Ball, and a visit by President Rutherford B. Hayes.

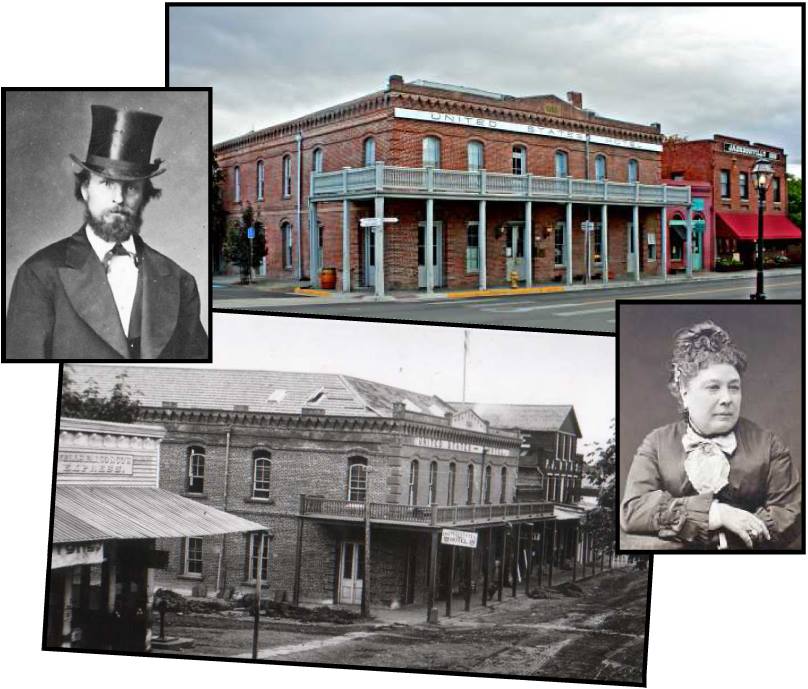

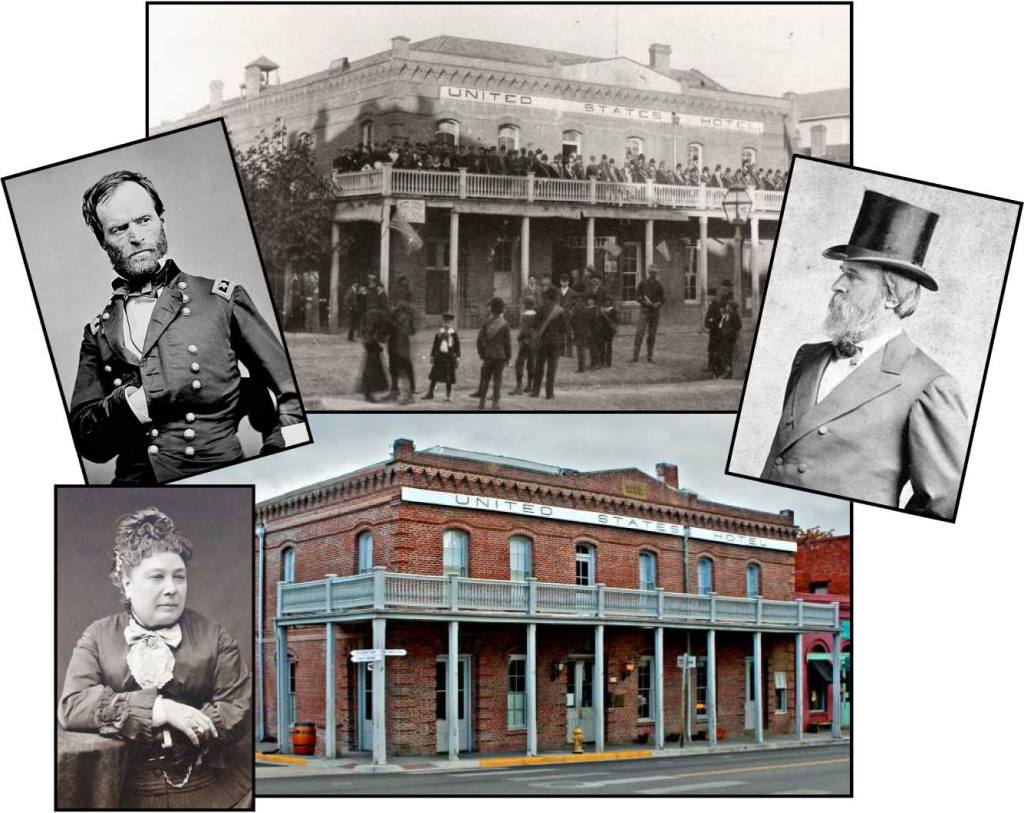

U.S. Hotel #1

The U.S. Hotel, located at the northeast corner of California and 3rd streets in Jacksonville, looks much as it did when local brick mason George Holt constructed it in the late 1870s for his wife, hotel proprietress Madame Jeanne de Roboam Langier Guilfoyle Holt. De Roboam, who had established the Franco-American Hotel as a famous regional hostelry, longed for a grand brick hotel. It was even rumored that she married Holt in order to fulfill her dream.

U.S. Hotel #2

Shortly after the U.S Hotel was completed in 1880, Jacksonville and proprietress Madame Jeanne DeRoboam Holt welcomed President Rutherford B. Hayes and his entourage for an overnight visit with brass band, speeches, and elegant dinner. Madame Holt also presented the presidential party with a bill double that charged by San Francisco’s finest hotel. General William Tecumseh Sherman, a member of the presidential party, complained about the cost, saying they didn’t want to buy the hotel, only to rent rooms. Madame Holt is said to have replied that the President of the United States could afford to pay a little more than common people….

U.S. Hotel #3

Following his sister’s death in 1884, Jean St. Luc de Roboam, inherited the U.S. Hotel, located at the northeast corner of California and 3rd streets in Jacksonville. He and his wife, wealthy widow Henrietta Schmidling, made a number of improvements, including a skating rink. But with the cost of renovations, DeRoboam soon accumulated unpaid mortgages, the lenders foreclosed, and the hotel went on the sheriff’s auction block. Henrietta saved the hotel by making the highest bid—$4,325 in gold coin from her own inheritance.

The Warehouse Store

We wish the Jessers well with their new Ashland store, the Culinarium, although we bemoan our loss of the Jacksonville Mercantile. However, the building at 120 East California Street has seen a lot of reincarnations over the years. Built as a warehouse around 1861, it was later home to The Oregon Sentinel and the Luy and Keegan Saloon. In 1931, it was Amy’s Café—a combination of saloon, restaurant, market and bookstore. It was subsequently a grocery store, then a book store, before becoming the Mercantile. Who knows what it’s next incarnation will be!

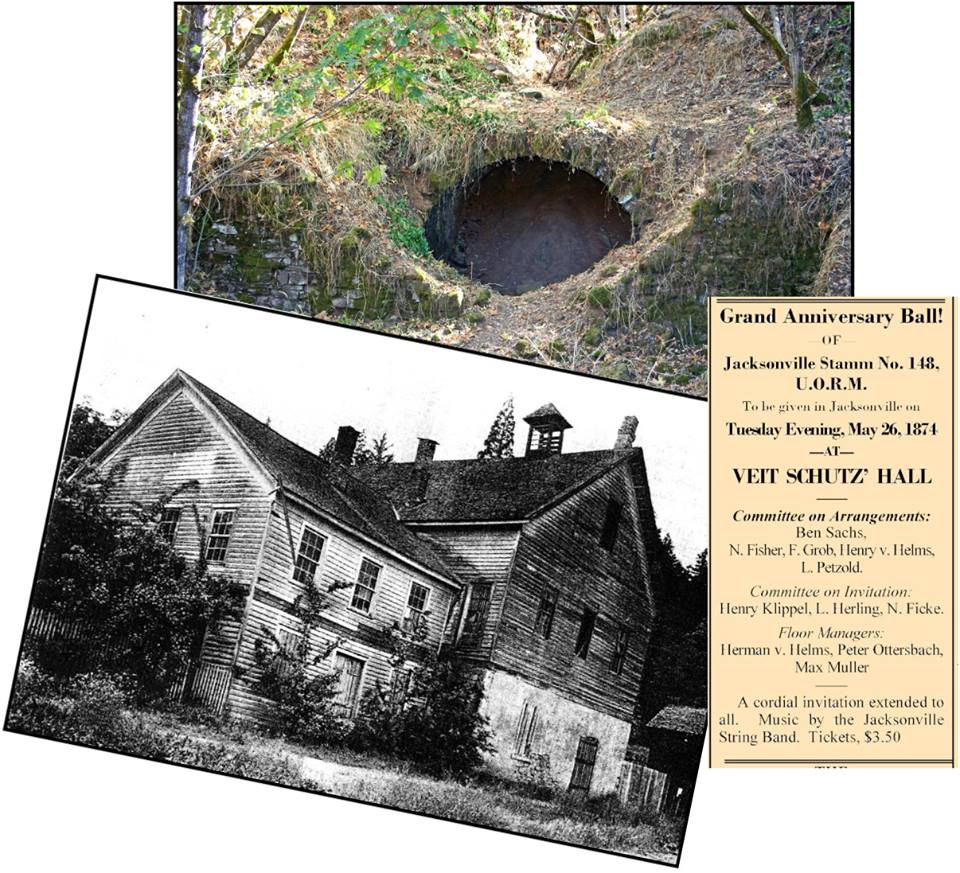

Veit Schutz Hall

As you climb the stairs from Highway 238 to the Lower Britt Gardens in Jacksonville, have you ever wondered about the stone walls and cavern you see on your left? That was the cellar and barrel cave of Veit Schutz Hall, the largest brewery in Jacksonville. Constructed in 1856, it also featured a bar and an elaborate dance hall. A prominent local attorney wrote the following lines in 1874:

“Oh! Dear Walter, I like to recall

The pleasure we had at Veit Schutz hall

The fun that we had I’ll n’er forget

Nor will I ever those days regret….”

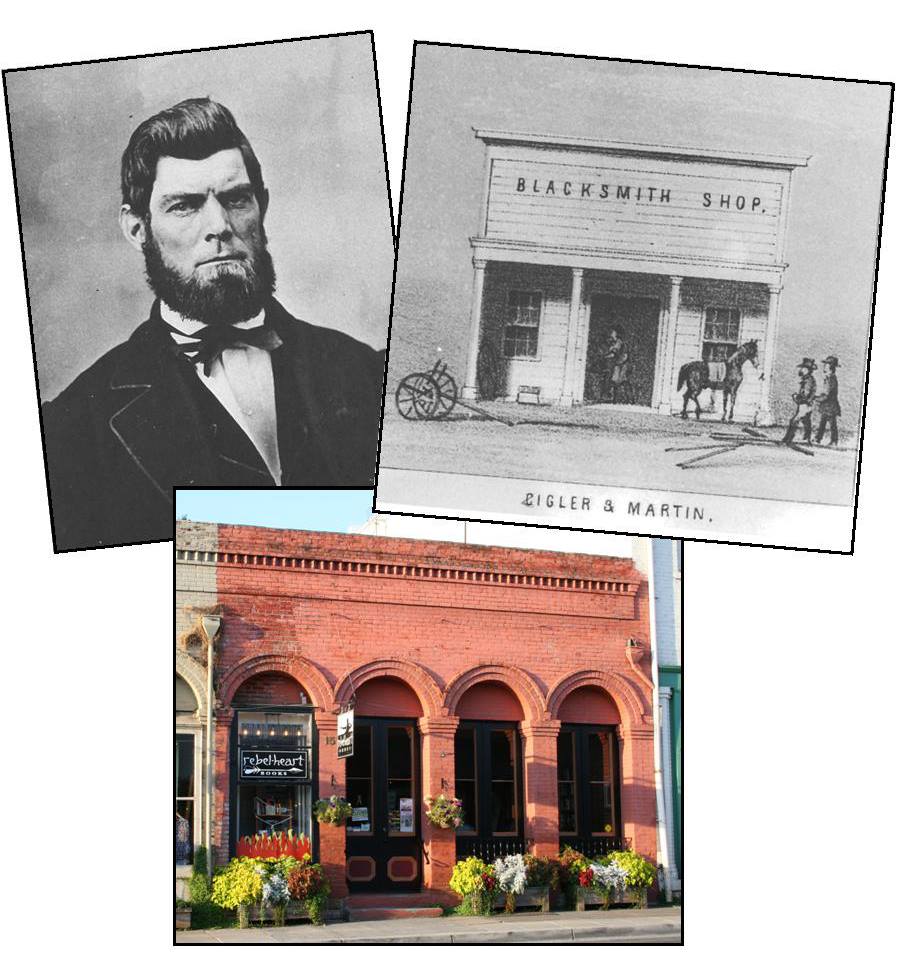

Zigler and Martin Blacksmith

From as early as 1852, an almost unimaginable conglomeration of frame shops, sheds, and outbuildings lined the intersection of Jacksonville’s California and S. Oregon streets. Among them was the Zigler and Martin Blacksmith shop. It supposedly stood at 157 W. California Street, now home to Rebel Heart Books. Louis Zigler was a miner, blacksmith, proprietor of the Adams Hotel, and at one time the County Sheriff. However, by 1870 he had moved his family to Roseburg. Alex Martin, his partner, appears to have gone into the general merchandise business. The fire of 1874 wiped out this entire block, but was quickly replaced by the current brick structures.

California & Oregon Street Crossroads #1

One legend has it that the crossroads of California and Oregon streets were so named to avoid the tax collectors. Oregon tax collectors were supposedly told they were in California; California tax collectors were told they were in Oregon. True or not, many businesses have occupied the prime commercial location at the northeast corner of that Jacksonville intersection. One of the earliest was David Linn’s furniture factory, showroom, and planing mill. When it burned in an 1888 arson fire, J.C. Whipp’s marble works took its place. Around the turn of the century, millwright John Lyden expanded Whipp’s display room into the Lyden House which became a popular boarding house and restaurant. A 1962 Mail Tribune wrote the Lyden House obituary. Sometime after 1962 the Lyden House was torn down and replaced by the current telephone exchange building.

One legend has it that the crossroads of California and Oregon streets were so named to avoid the tax collectors. Oregon tax collectors were supposedly told they were in California; California tax collectors were told they were in Oregon. True or not, many businesses have occupied the prime commercial location at the northeast corner of that Jacksonville intersection. One of the earliest was David Linn’s furniture factory, showroom, and planing mill. When it burned in an 1888 arson fire, J.C. Whipp’s marble works took its place. Around the turn of the century, millwright John Lyden expanded Whipp’s display room into the Lyden House which became a popular boarding house and restaurant. A 1962 Mail Tribune wrote the Lyden House obituary. Sometime after 1962 the Lyden House was torn down and replaced by the current telephone exchange building.

California & Oregon Street Crossroads #2

From around the mid-1890s to 1962, the Lyden House stood on the corner of California and Oregon streets at the site of today’s telephone exchange building in Jacksonville. John Lyden and his wife Mary ran the boarding house, charging 35 cents for a night’s lodging in one of its 11 rooms. Rooms were furnished with wash stands, a pitcher, a wash bowl, a chamber pot commode, a “well supplied” towel rack, an iron bedstead with ample bedding, and a good supply of “Buhac” used to discourage unwanted bedfellows. The hotel was usually full by nightfall. About 1903, Mary Lyden and 2 of her daughters started the “Hooligan Restaurant.” It became famous for its “good homey table” and “wonderful filling meals,” served for 65 cents. Special dinners could also be ordered. The enterprising Lydens also carried a good supply of items such as pots, pans, canteens, and other tinware in demand by miners and prospectors still hoping to strike it rich in the hills around Jacksonville.