Baseball Field (now Ray’s Market)

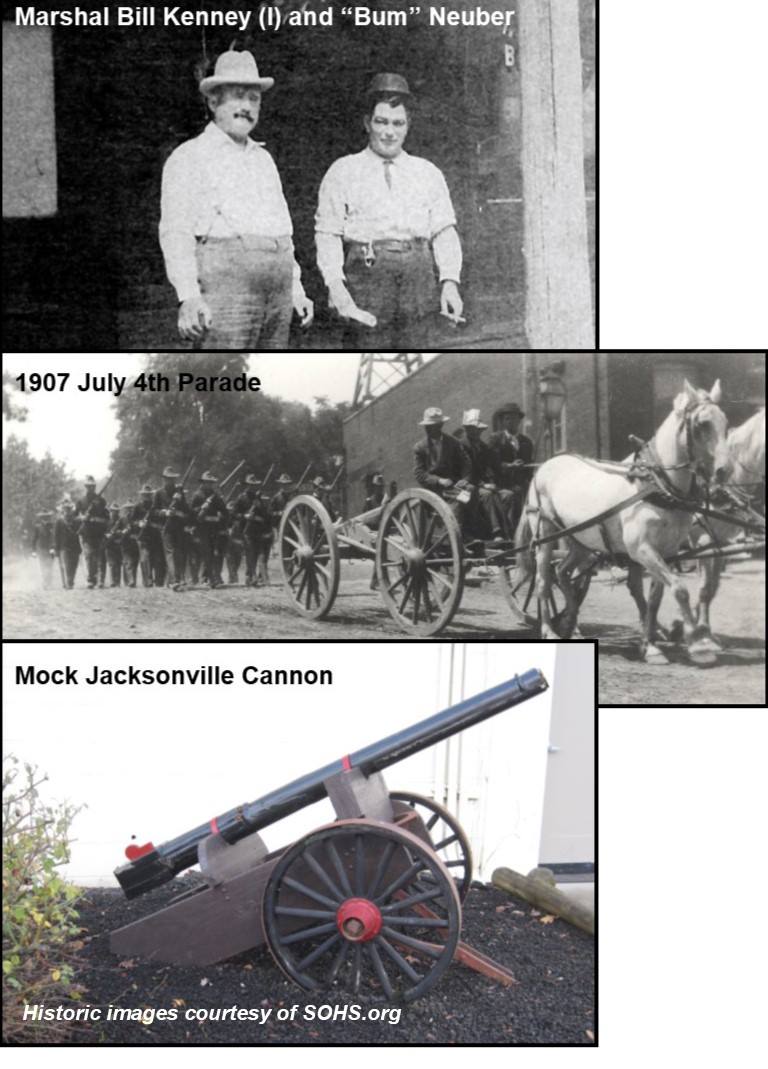

The city block on North 5th Street occupied by the local Ray’s supermarket was Jacksonville’s baseball field in the early 1900s, home to the Jacksonville Gold Bricks baseball team. Team owner, George “Bum” Neuber, was known to bring in “guest players” as a means of defeating visiting teams. Neuber ran a card room in town for the adults, and welcomed children to the petting zoo he set up in his backyard.

Britt Festival

Like many things, it began with a dream….

After John Trudeau, principal trombonist with the Portland Symphony (now the Oregon Symphony) played trombone in the early 1950s at Massachusetts’ Tanglewood Music Festival, summer home of the Boston Symphony, he dreamed of establishing a summer music festival on the west coast.

When John’s close friend Sam McKinney discovered Jacksonville on a summer trip to Southern Oregon in August 1962, he thought of John’s music festival dream. When John and Sam drove down from Portland, the Britt hillside immediately captured their attention. Though overgrown with waist-high grass and weeds, its panoramic view of the valley, the giant trees, and the natural acoustics of the hill seemed perfect.

The idea of a music festival fit perfectly with the Mayor’s and City Council’s ambitions for revitalizing Jacksonville. Once given the green light, Trudeau realized the tremendous scope of what had to be done to plan a music festival for the following summer: catalyzing the community, recruiting a board, preparing the venue, recruiting musicians, putting together programs, just for starters. Hundreds of one-on-one conversations and frequent trips between Jacksonville and Portland were involved.

As word spread, classical music lovers from Medford and surrounding communities began to participate. Volunteers, professional and non-professional, worked side by side and the impossible was achieved.

On August 11, 1963, Trudeau stepped onto the stage as the first orchestra conductor and Jacksonville’s Britt Music Festival became the first outdoor music festival in the Pacific Northwest. It began on a temporary plywood stage strung with tin-can lights. The roof was canvas draped from donated telephone poles, and concertgoers sat on the naturally sloped woodland hillside. And the reset, as they say, is history. A beautiful view, wonderful natural acoustics, and the hard work and enthusiasm of a generous community gave birth to what has become the Britt Festivals we celebrate every summer!

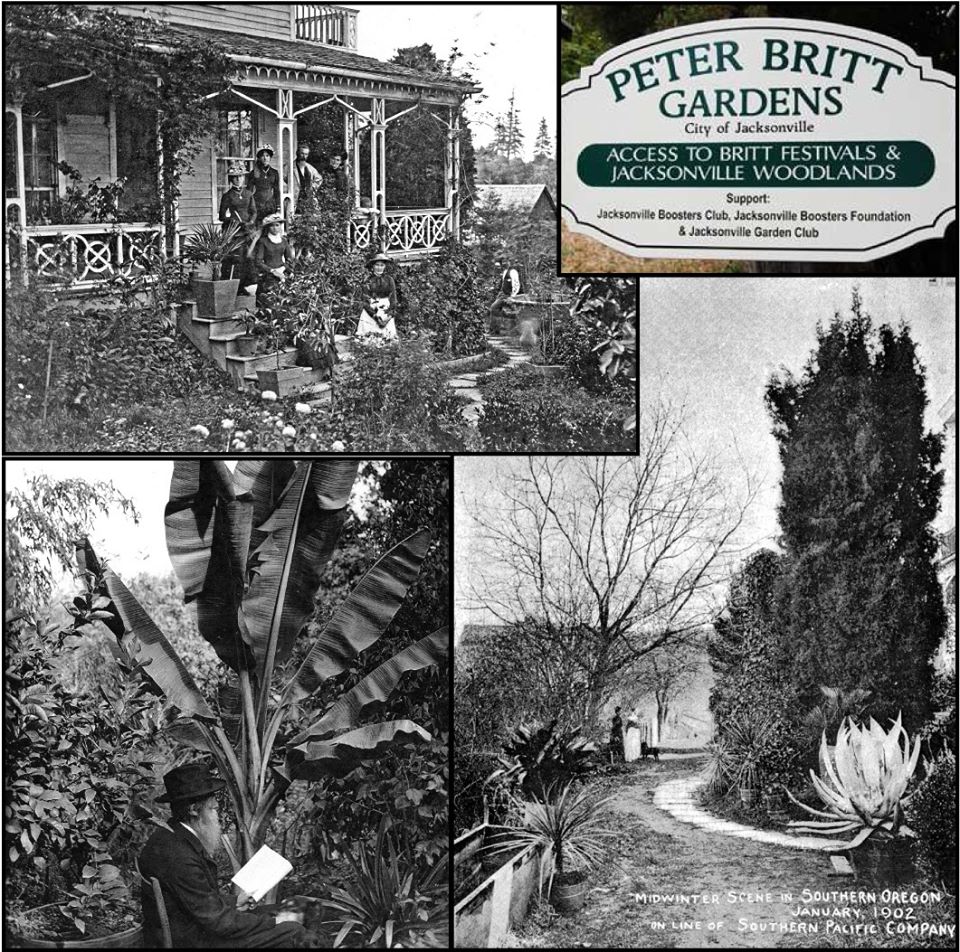

Britt Gardens

On March 6, 2020, the Peter Britt Gardens became the newest Jacksonville’s landmark to be recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Home to Swiss-American entrepreneur Peter Britt and his family from 1852 to 1954, his homestead fronting on 1st Street now houses the Britt Festival grounds, the Britt Gardens, and a popular Jacksonville Woodlands trailhead. Although he arrived in Jacksonville with only $5 in his pocket and a cart of photography equipment, Peter Britt became a renowned photographer, agricultural innovator, and capitalist. Britt’s photographs documenting prominent people, places and events in the second half of the 19th century were known throughout the Pacific Northwest. Britt helped pioneer the pear orchards that became a powerful driver of the region’s economy in the 20th Century and the grape cultivation and wineries that lead part of the region’s 21st century economy. Britt is also known for creating lavish Victorian botanical gardens on this property that became a popular Pacific Northwest tourist destination. The National Historic Landmark Designation, submitted by archaeologist Chelsea Rose, deems Britt’s homestead a landmark of statewide significance, home to two generations for over 100 years and augmented by a robust documentary record of photographs, diaries, letters, and family heirlooms. You can read the full story in the Jacksonville Review on-line: Jacksonville Landmark Peter Britt Gardens Added to National Register

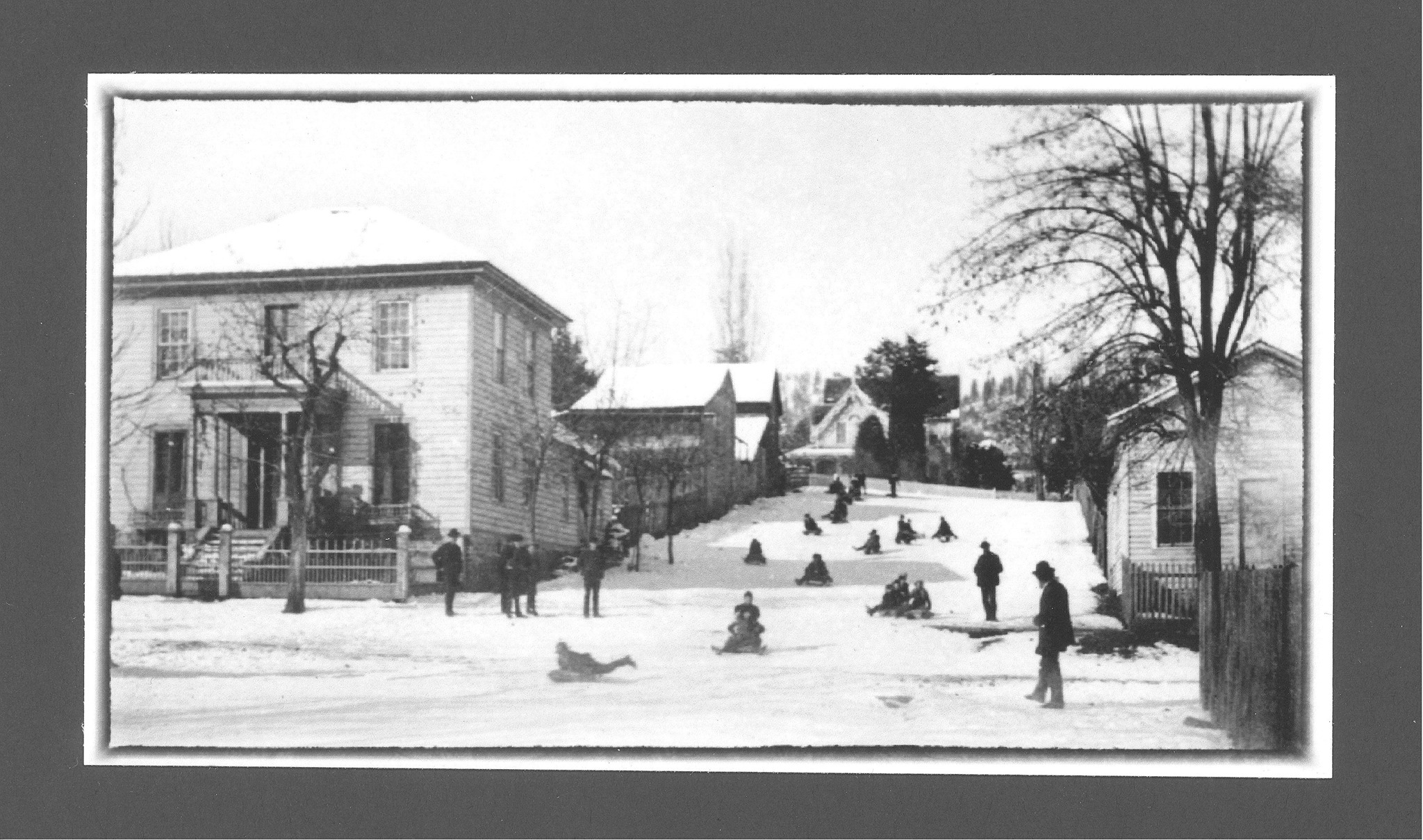

Britt Hill

We’ll wish you some very happy holidays with this photo from the late 1800s of sledding on Jacksonville’s Britt Hill. The vantage point is the corner of Pine and South Oregon streets. Herman von Helms house is on the left corner with stables and a shed behind it, and Peter Britt’s house can be seen at the top of the hill on 1st Street.

Broom & Fan Brigades

Our pioneer forefathers didn’t have TV, radio, or movies to entertain them; they had to create their own amusements. Most could play an instrument, sing a tune, or recite a poem when called upon. Tableaux depicting popular images were also frequent in-home entertainment. By the 1880s, inspired by reunions of Civil War soldiers, young ladies began forming drill teams and executing precise drill routines. Manuals were even published to illustrate appropriate movements. Jacksonville is known to have had a scarf team, a fan brigade, and a broom brigade. The latter was especially commended in local newspapers for the way in which it executed the commands of its drill-master “in marching, counter-marching, wheeling, advancing, and handling their ‘deadly weapons.’” Following the brigade’s performance at an 1889 benefit, the teams’ brooms were even auctioned off. The brooms realized the handsome sum of $8 for the cemetery well fund.

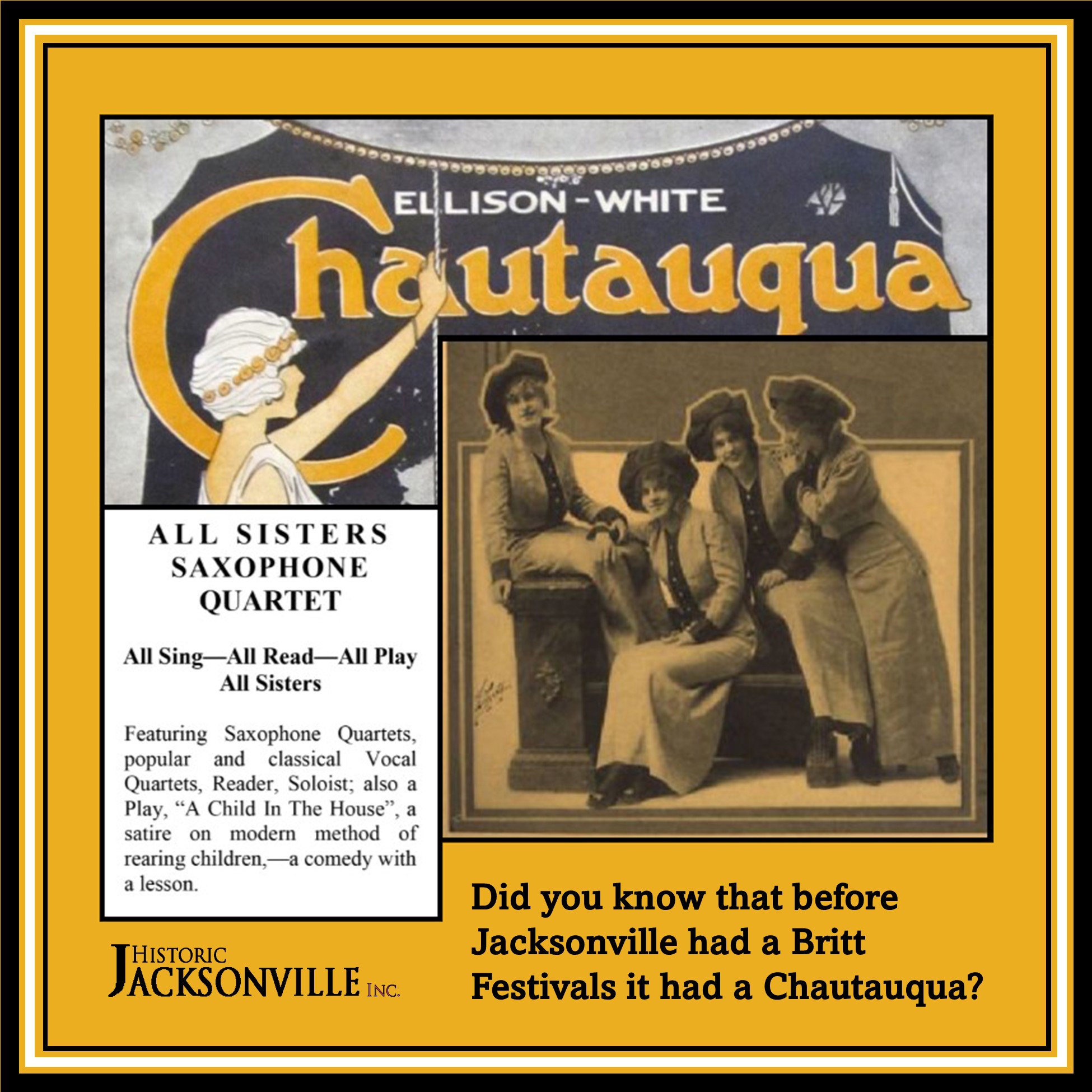

Chautauqua

Did you know that before Jacksonville had a Britt Festivals, it had a Chautauqua?

Chautauqua was a highly popular adult education movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that brought speakers, teachers, musicians, showmen, and preachers to cities and rural communities. President Theodore Roosevelt described Chautauqua as “the most American thing in America.”

In 1924 and 1925, an inspired Jacksonville City Council persuaded enough backers to secure a week of entertainment from the Ellison-White Chautauqua Company. Lacking a grand auditorium or park, Jacksonville’s first season was held in the high school gymnasium; the second in the U.S. Hotel ballroom. Season tickets sold for $2, enough to secure “wholesome college-type entertainers who presented genteel program material.”

One of the highlights of the first season was the Rouse “All Sisters Quartet,” 4 saxophone-playing sisters from Iowa. Regrettably, both seasons ended in a deficit. Medford was campaigning to become the county seat, Jacksonville was becoming a backwater, and citizens had become more concerned with necessities than culture. But for this brief period in the 1920s, Jacksonville still enjoyed a touch of glamor!

Chinatown

Jacksonville was home to the first Chinatown in Oregon, located along West Main in the area where Gogi’s, Elan Guest Suites, and Veterans Park are now to be found. This area was the town’s original commercial center, but as businesses relocated to California Street in the 1850s, this block became home to hundreds of Chinese workers brought here by labor bosses to work the gold mines. As the gold played out, the Chinese Quarter was gradually abandoned. In 1888, most of what were by then derelict buildings burned in one of Jacksonville’s many fires.!

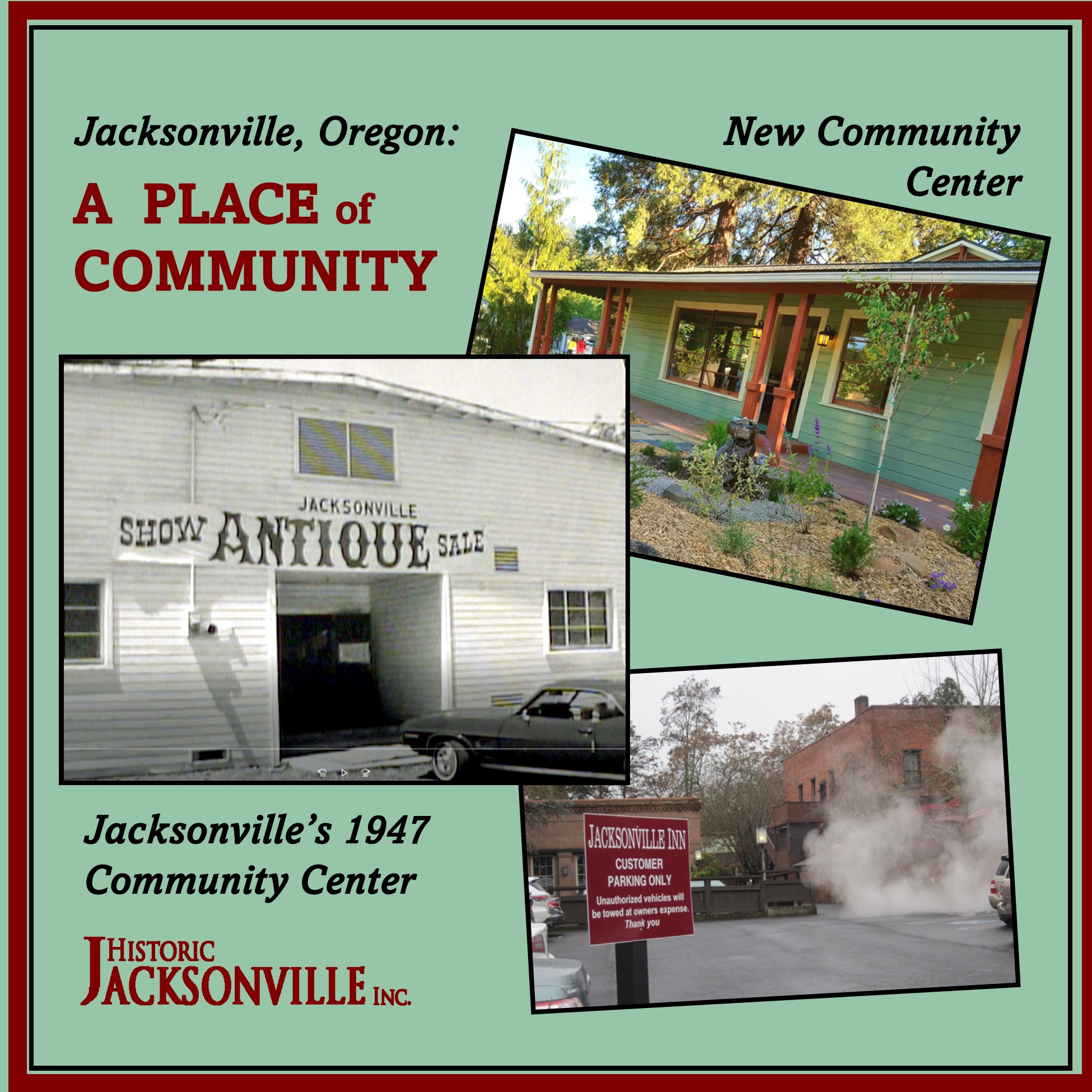

Community Center #1

Community Center #2

We hope that you are enjoying the many programs and activities being offered by the Jacksonville Community Center. However, the remodeled and expanded Sampson/Miller building is not the town’s first gathering place. Local fraternal buildings and breweries served that function for years after the town’s founding.

Then in 1947 when Camp White buildings were being sold after World War II, the City, and/or the Lions Club, purchased some of their “surplus” and constructed an actual community center at the corner of C and North 4th streets to serve as a meeting and social gathering spot for adults and kids alike. Longtime residents recall it being the site of after-school activities, teen dance classes, and community Christmas gatherings. The Presbyterian Women prepared monthly suppers for the Jacksonville Lion’s Men’s Club. A 1953 Mail Tribune mentions the Hall as the site of the Jacksonville Volunteer Fire Department’s annual November ball.

However, by the 1960s, the Community Center was becoming run down and the Saturday night dances had become rowdy. Mayor Jack Bates bought the community center building and the adjacent P.J. Ryan building and began restoration work on the latter—part of Jacksonville’s revival after becoming the first West Coast district on the National Historic Landmark registry. In 1968, Bates tore the old community center down to serve as a parking lot for his new Jacksonville Inn. Jacksonville’s original community center building was a “thing of the past.” But community plays a key role in Jacksonville. And now we can boast of our multi-purpose community facility at the corner of Main and South 4th streets!

Early Newspapers

Early Jacksonville had a succession of newspapers over the years, many of them competing and espousing opposing political viewpoints. When the Democratic News plant was destroyed in the fire of 1872, it rose again as the Democratic Times. Initially housed in the Orth Building on South Oregon Street, the Times soon outgrew that space and established its own offices at the corner of C and North 3rd streets. The Times lasted into the early 1900s when it merged with the Southern Oregonian. Depression era miners of the 1930s uncovered the Times doorstep as they undermined almost every inch of Jacksonville. The current private residence was built as a rental property in the 1930s over one of these old mine shafts.

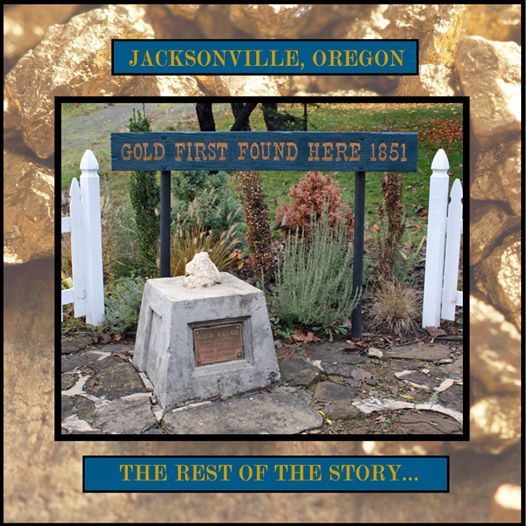

First Gold Found Here

Of all the Jacksonville, Oregon “firsts,” the question of who first found gold may be the most debatable. The “Gold First Found Here” marker on Applegate Street where it crosses Daisy Creek would have you believe that James Clugage and James Pool, two packers carrying goods to the mining camps in California, did a little panning in the creek in the winter of 1851-52 and found the first “color.”

But the story is a little more complex than the marker would have you believe. Several gold discoveries had been made in the Illinois Valley at Josephine and Canyon creeks and Sailor’s Diggings in 1851 before the first Rogue River Indian War broke out.

And the previous fall, the son of Alonzo Skinner, the local Indian agent, and one of his employees, a Mr. Sykes, had found gold in nearby Jackson Creek. Clugage and Pool learned of their discovery when they spent a night at the Skinner homestead. So, before heading to Yreka, Clugage and Pool took time to pan a little and, voila!

Clugage and Pool hightailed it south and immediately filed land claims on what is now most of Jacksonville. They returned and spent the next few weeks mining, but then Clugage did something unheard of—he publicized his “find,” even boasting to California newspapers of taking out 70 ounces of gold a day from his claim. Thousands of miners poured over the Siskiyous into the Valley, closely followed by merchants, gamblers, courtesans, and settlers—all needing a mining, business, or home site.

In the case of Jacksonville’s gold discovery, the honor of “first” probably belongs to Skinner and Sykes. But Clugage may have found the mother lode—he made a fortune selling land!

First Wedding in Jacksonville

In January 1853, Col. John England Ross and Elizabeth Hopwood were married—the second wedding in Jackson County and the first in Jacksonville. Naturally, all the town folk were invited. Elizabeth had a special wedding dress made for the ceremony, but Ross had nothing but his buckskins. The ladies of Jacksonville fretted over this lack of proper wedding attire.

Jane McCully offered Ross a white shirt that belonged to her husband, but Dr. McCully’s smaller stature meant the fit was strained at best. When the nervous bridegroom joined a jumping contest with some of the men attending the ceremony, Ross’s exuberance split the shirt down the back. Jane quickly poked holes down each side of the split, laced it together with string, and the wedding proceeded as planned.

With no church and no place large enough to accommodate everyone, Ross and Elizabeth were married on the corner of Main and Oregon next to the town pump, even though it was early January. The Methodist preacher, Reverend Gilbert, presided. The groom was 35; the bride, 18.

The occasion was obvious cause for a jubilee. A progressive supper went house to house, ending with a spectacular wedding cake improvised from duck eggs, brown sugar, and bear suet. A grand ball, probably at one of the local saloons, capped the evening.

“First White Child Born in Jacksonville“

The title of “first white child born in Jacksonville” has been a subject of debate for over 150 years given there are multiple claimants. The issue is clouded since “firsts” are usually awarded in retrospect and memories can be unreliable. Also most individuals reporting on the subject credited any event happening in southern Oregon to Jacksonville because that was the closest town, the name known to them, and subsequently the County Seat.

August 11, 1852, the earliest known birth date, belongs to Bruce Evans. In 1903 he applied for a passport and listed his birthplace as Jacksonville. There is a 2-year-old Bruce Evans listed in the 1854 Jackson County Territorial Census. However, the only Evans family on record at that time lived near what is now Rogue River. Beginning in 1851, Davis “Coyote” Evans operated a ferry on what became known as Evans Creek, a tributary of the Rogue.

A second claimant is Cornelius Jasper Armstrong, born February 24, 1853, to Robert and Minerva Armstrong. When the Armstrong family arrived in 1852, Robert and Minerva settled on a farm 4 miles north of Jacksonville at the base of the western hills. They did not move into Jacksonville until 1890.

A third claimant is James Clugage McCully, born August 27, 1853, to Jane and John McCully and named after James Clugage, one of Jacksonville’s “town fathers.” We do know the McCully’s lived in town, initially in a log cabin on the property at the corner of California and South 5th streets where the McCully House now stands.

In the 1850s, babies were born at home. So while Bruce Evans may lay claim to the title “first white child born in Jackson County,” we’ll give the title of “first white child born in Jacksonville” to James Clugage McCully.

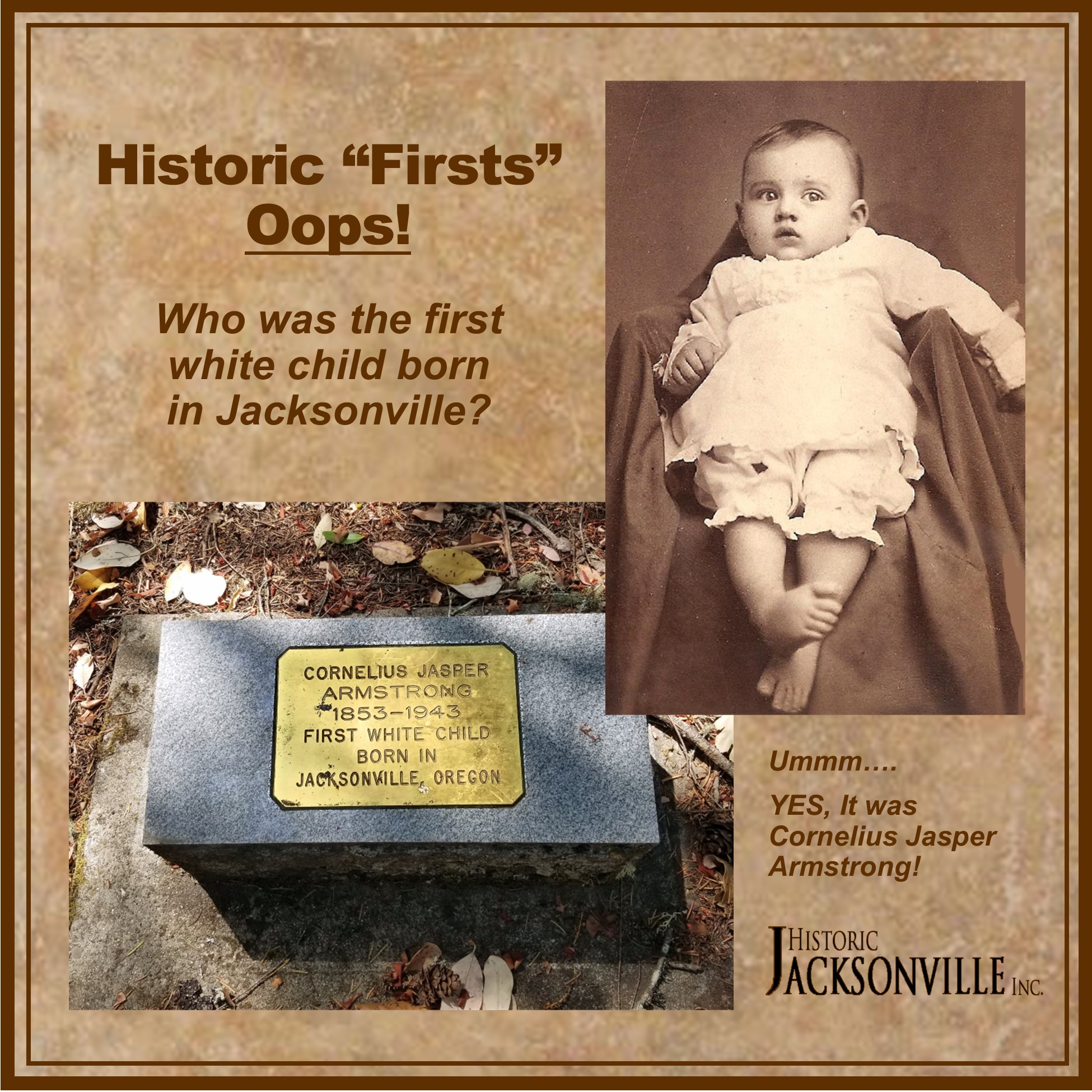

“First White Child Born in Jacksonville” – OOPS

We’re eating crow. As noted when we started on the subject of “firsts,” claims can be unreliable since “firsts” are usually awarded in retrospect and memories can be unreliable. Information can also be missing. And we just came across information that restores the title of “first white child born in Jacksonville” to Cornelius Jasper Armstrong!

When Robert and Minerva Armstrong arrived in Jacksonville in October of 1852, Robert built a “pole cabin” on the site of what is now known as the “Judge Hanna House” at 285 South 1st Street. That’s where Cornelius Jasper Armstrong was born on February 24, 1853. It was later that spring that the Armstrongs traded the pole cabin and a hack to a Mr. Rogers for the donation land claim about 4 miles north of town that the Armstrong family occupied for the next 37 years.

So Cornelius Jasper was indeed born in Jacksonville!

Gold Bricks Baseball Team

We’re in the middle of the World Series, so it’s “batter up” for History Trivia Tuesday! Our friend Bill Miller’s “History Snoopin’” article in the October 28th Mail Tribune reminded us that before Medford had U.S. Cellular Field, baseball games were played at Miles Field—now the site of Medford’s south Walmart. Well, did you know that Jacksonville used to have a baseball field too? The city block on North 5th Street occupied by the local Ray’s supermarket was Jacksonville’s baseball field in the early 1900s, home to the Jacksonville Gold Bricks baseball team. Team owner, George “Bum” Neuber, was known to bring in “guest players” as a means of defeating visiting teams. Neuber was quite the character. He also ran a card room in town for adults while welcoming children to the petting zoo he set up in his backyard.

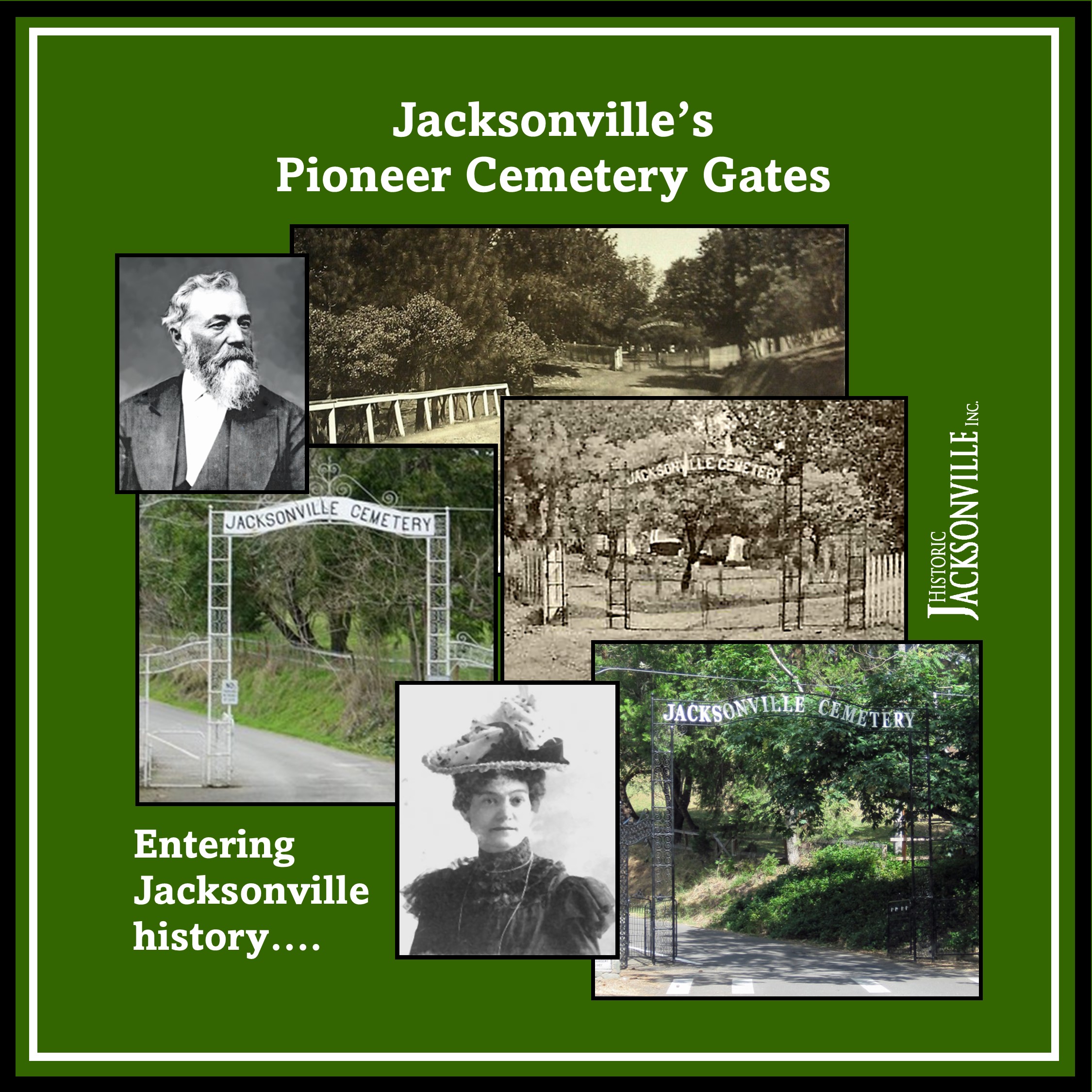

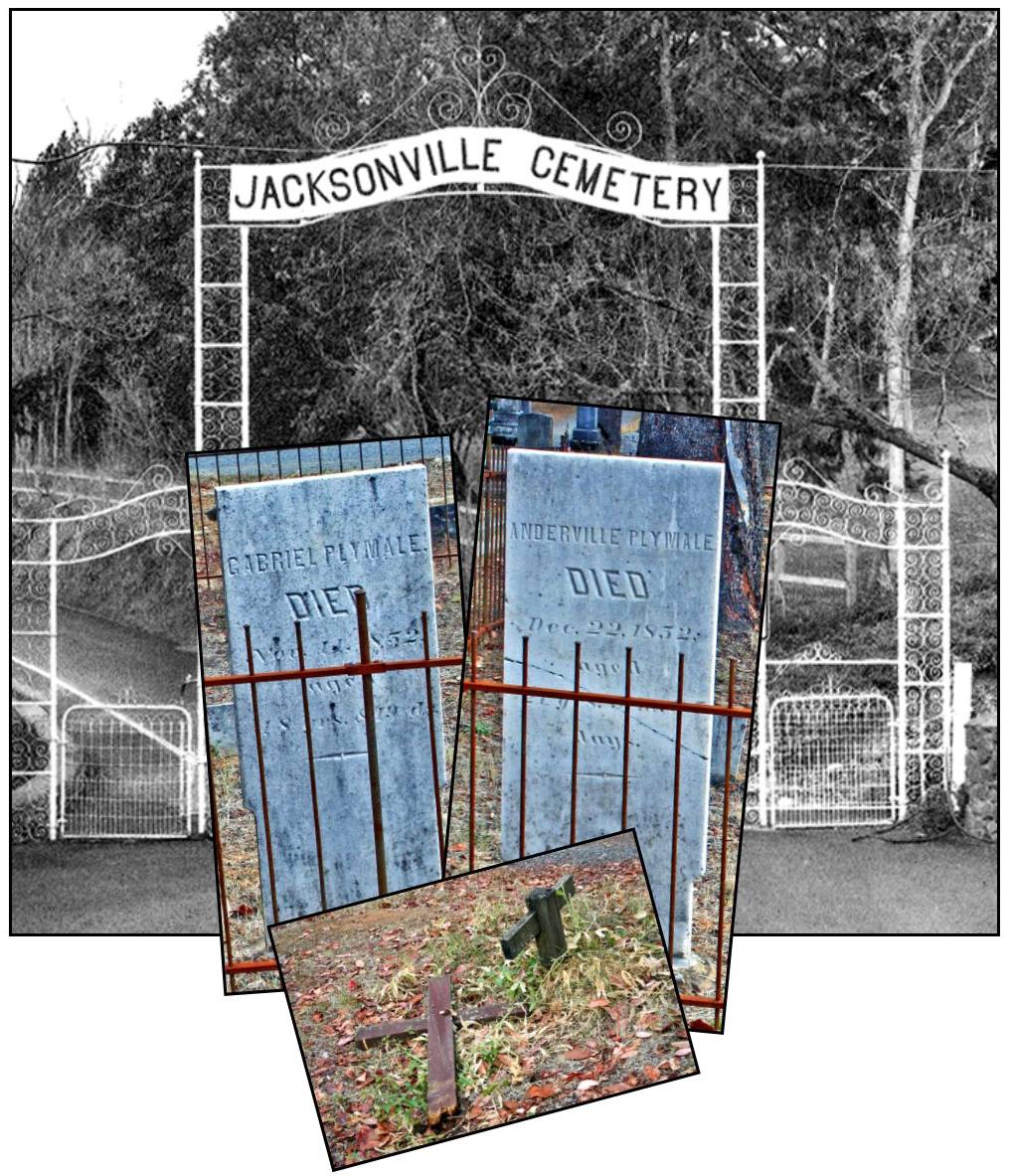

Jacksonville Historic Cemetery #1

Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery, located at the end of West “D” Street, is one of the oldest cemeteries in the Pacific Northwest and one of the few that has remained in continuous use. Its 32 acres contain over 4,000 grave sites. The cemetery was platted in 1859 and dedicated in 1860, but there are headstones with earlier dates. Before this cemetery opened, it was common for settlers to have family graveyards on their own property. Later some chose to move loved ones to the community cemetery. Two such are Gabriel and Anderville Plymale, father and son, the earliest recorded deaths in Jacksonville. Having survived the 2,000 mile trek across the Oregon Trail, they arrived in Jacksonville in October of 1852. Gabriel died within the month from “swamp fever,” more commonly known as typhoid fever. Anderville died just three weeks after his father. There was no cemetery at the time, so they were buried at the bottom of the hill. When the cemetery opened in 1860, they were brought here to their final resting place.

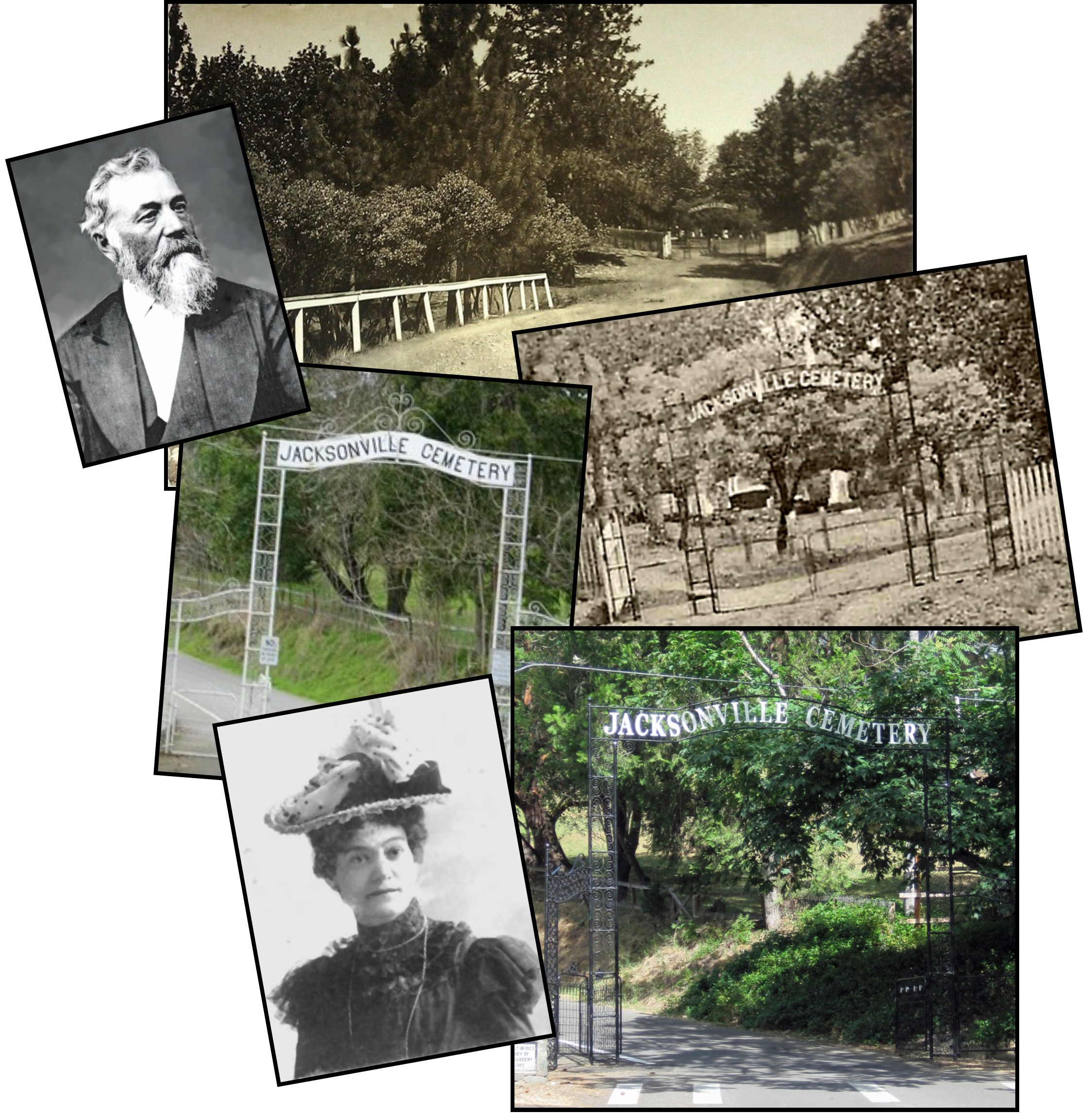

Jacksonville Historic Cemetery #2

Have you had a chance to admire the new gate to Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery on West E Street? Installed in the fall of 2018, the new gate’s white lettering and black wrought iron replicates the original gate erected about the time the cemetery officially opened in 1860. When James Napper Tandy Miller set aside the original acreage for a town cemetery in 1859, he required the cemetery to be fenced to protect against the intrusion of wild animals. But when the cemetery opened, the gate was at the top of the hill! The dirt access road (now Cemetery Road) that led to the entry presumably followed an old Indian trail. In 1923 Alice Applegate Sargent funded the Cemetery Road wall in memory of her husband, Col. Herbert Howland Sargent. Around the time the wall was built, the original cemetery gate was replaced, and the entry relocated to the bottom of the hill. The 2018 gate replaces the familiar white iron gate erected in the early 1900s. The Jacksonville cemetery is one of the oldest pioneer cemeteries in the Pacific Northwest and has remained in continuous use since its founding. Join the Friends of Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery for guided tours, evening strolls, workshops, and their annual “Meet the Pioneers” event.

Jacksonville Historic Cemetery #3

When James Napper Tandy Miller set aside the original cemetery acreage in 1859, he required the cemetery to be fenced. A white picket fence was erected at the top of Cemetery Hill, but the original gates were probably wood. At some point the wooden gates were replaced with the familiar metal arch and gates. Photos show they were there no later than 1912 but did not date to the cemetery’s official opening in 1860.

Later the original metal arch and gates were moved to their current location at the bottom of the hill—possibly in 1923 in conjunction with Alice Applegate Sargent funding the Cemetery Road wall in commemoration of her husband. Pieces were subsequently added to the arch and gates to increase their height and width, allowing motorized vehicles to pass through and under.

The arch and gates that now sit at the entrance to the cemetery are the same arch and gates that originally sat at the top of Cemetery Road. In 2018, the City of Jacksonville paid for them to be restored to their original color and state—with one exception. The side pieces were angled to increase the structure’s stability, allowing an increase to the width of the entry of one of the oldest pioneer cemeteries in the Pacific Northwest.

Jacksonville Library

During Jacksonville’s early years, books were precious and access limited. Middle and upper-class women and men established “reading circles,” a way to share books as well as being opportunities for intellectual stimulation and socializing. Early attempts to provide library services included a subscription circulating library; a Catholic library established by the local priest; and a Young Men’s Library & Reading Room Club. At one time even the back room of the Beekman Bank served as a library.

In 1885, Jacksonville residents began fund raising efforts for a public library, but it was 1908 before a free public library was finally established for town residents. The Library Association rented the “Beekman building on Main Street” and fitted up a reading room with table, bookcase, desk and chairs. It was initially stocked with 50 books from the State traveling library, 80 donated books, and a collection of Harper’s Monthly magazines dating from 1868. Library hours were Tuesday and Friday from 7 to 9 pm and Wednesday and Saturday from 2 to 6 pm. Books could be checked out for 1 week.

In 1920, Jacksonville, with a population of 489, was the first town to respond to a cooperative arrangement with the County, finding a “suitable room” in the 1855 Brunner Building at the corner of S. Oregon and Main streets—the oldest brick building still standing in Jacksonville and the Pacific Northwest. On 2 afternoons and 1 evening each week Mrs. H. K. Hanna, the first librarian, supervised the circulation of 290 books.

But long before the end of the 20th Century, the Brunner Building was a very “tight squeeze.” A 2000 County-wide bond measure funded construction of the current Jacksonville library on West C Street.

Today our Jacksonville Library is a major community resource, offering a wide range of children’s, teen, and adult collections (both physical and electronic) plus outreach services for elementary and middle school students, homebound patrons, and childcare centers. An ever-changing calendar of programs and events includes musical performances, lectures, art exhibits, classes, book groups, story times, and more.

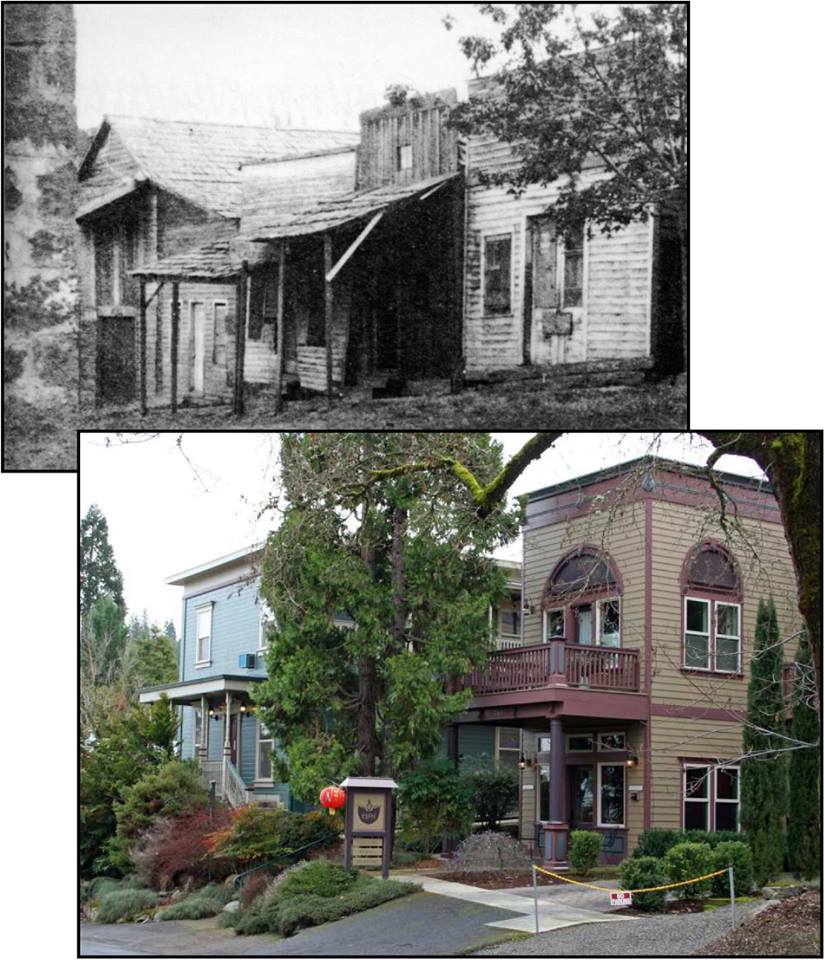

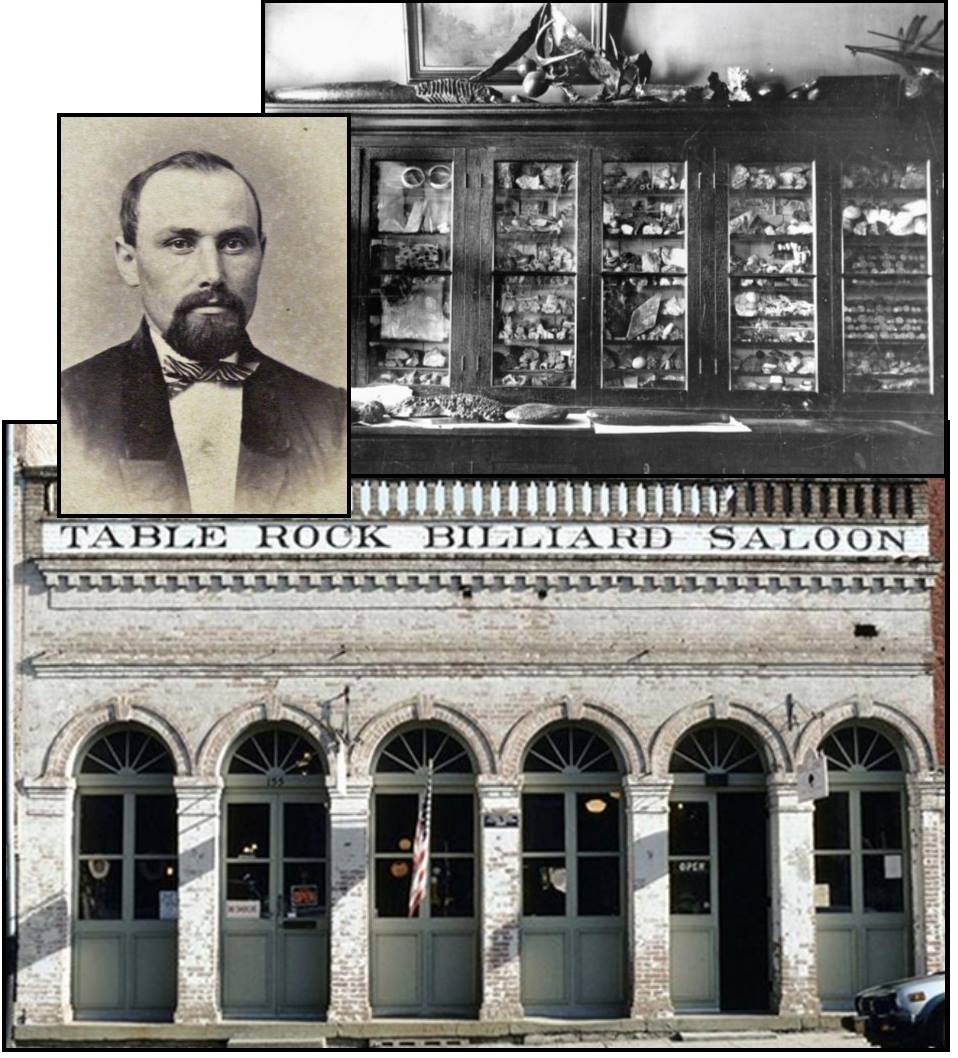

Jacksonville Museum #1-Table Rock Saloon

A museum has long been a feature of Jacksonville. The Table Rock Billiard Saloon, constructed in 1860 at 165 S. Oregon Street, was also Jacksonville’s first museum. Saloonkeeper Herman Von Helms collected fossils and oddities to attract a clientele that then stayed for his lager. When the saloon closed in 1914, the Helms’ “Cabinet of Curiosities” boasted a collection of artifacts valued at $50,000. It encompassed “every possible manner of relic…mutely telling pages in the early history of Jackson County.” Highlights included the first piece of gold found in Jacksonville, a photo and piece of rope from a hanging, and the first billiard table in the Oregon Territory. The billiard table was twice the size of those used today and was transported in sections on pack horses from Crescent City, CA. Today the Table Rock Saloon is home to the Good Bean coffee house, but you can still enjoy some Jacksonville history in the form of the 19th Century photos decorating the walls.

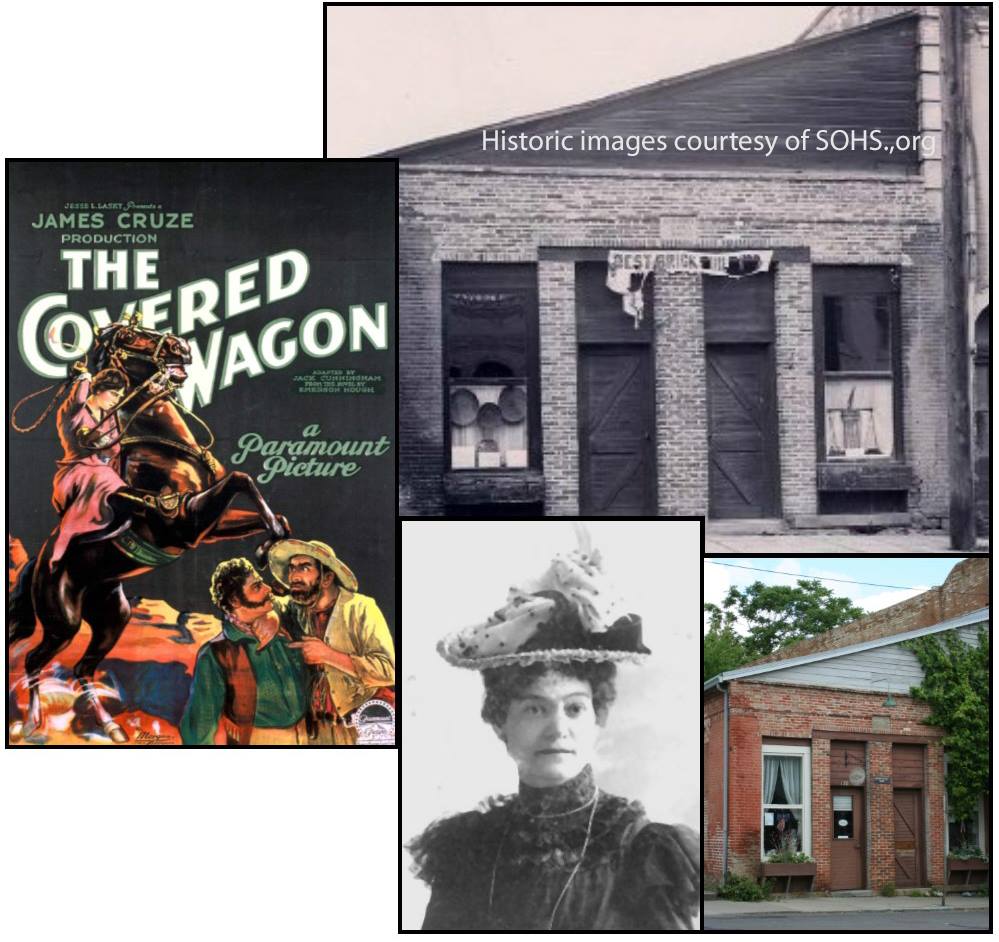

Jacksonville Museum #2 – Brunner Building

Shortly after the Table Rock Saloon closed in 1914, the residents of Jacksonville began lamenting the loss of its “Cabinet of Curiosities”—a collections of pioneer artifacts and relics that owner Herman von Helms had amassed. After Paramount Pictures released “The Covered Wagon” in 1923—the industry’s first historical “Epic Big Screen Western”—it intensified local interest in “old pioneer days” since the silent movie depicted the settlement of Oregon. “The Covered Wagon” became one of the most popular and critically acclaimed films of the first half of the 1920s, and a Jacksonville museum became more than wishful thinking. Inspired by the film and the upcoming Jacksonville reunion of the Pioneer Society of Southern Oregon, Mrs. Alice Applegate Sargent purchased the 1855 Brunner Building at the corner of Main and S. Oregon streets with the goal of creating “a repository for pioneer relics.” The museum opened briefly for the society’s annual meeting in October 1924, then had its formal opening February 27, 1925. Open on Tuesdays and Fridays, local newspapers reported that it attracted so many visitors that Mrs. Sargent and her assistant were kept very busy!

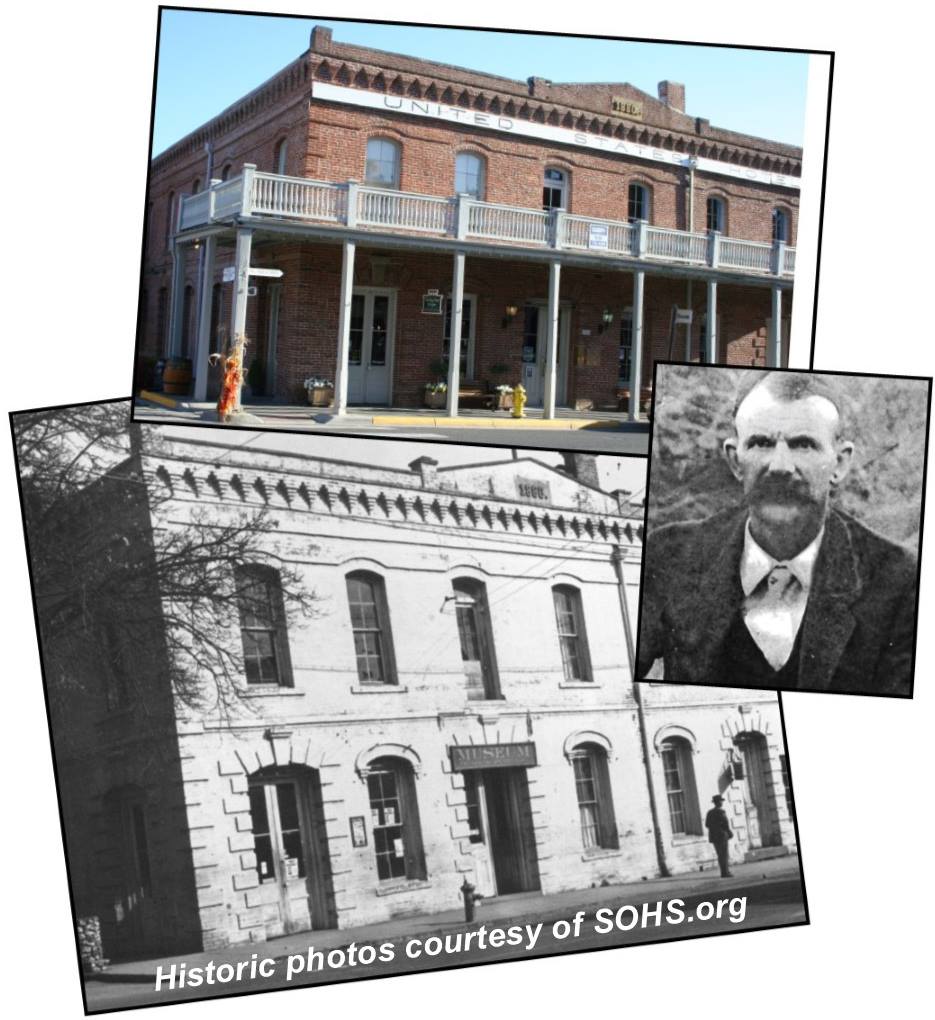

Jacksonville Museum #3 – U.S. Hotel

Soon after its 1925 formal opening, the 1-room Jacksonville museum in the Brunner Building operated by the Native Daughters of Jacksonville was deemed inadequate. More space was needed and as early as 1928 the Chamber of Commerce and City Council petitioned Jackson County for money to establish a museum in the U.S. Hotel on California Street. The County “took it under advisement.” In the 1930s, “a treasure house of junk and a handful of historical artifacts” was set up in what is now the Bella Union. The “Cabinet of Curiosities” from the old Table Rock Saloon was added to the collection along with other items from “historical minded folks.” Then local antique dealer Frank Zell stepped in. He had both a valuable collection of his own and an eye for history. But when crowded exhibits threatened to crash through the floor to the cellar below, Zell asked the City Council to move the museum to the U.S. Hotel—a goal embraced by local folk for over 10 years. The Council approved the move; the collection was transferred to the U.S. Hotel; and the U.S. Hotel became the Jacksonville Museum. Visitors sometimes contributed a quarter to the kitty, and Jacksonville acquired its first tourist attraction.

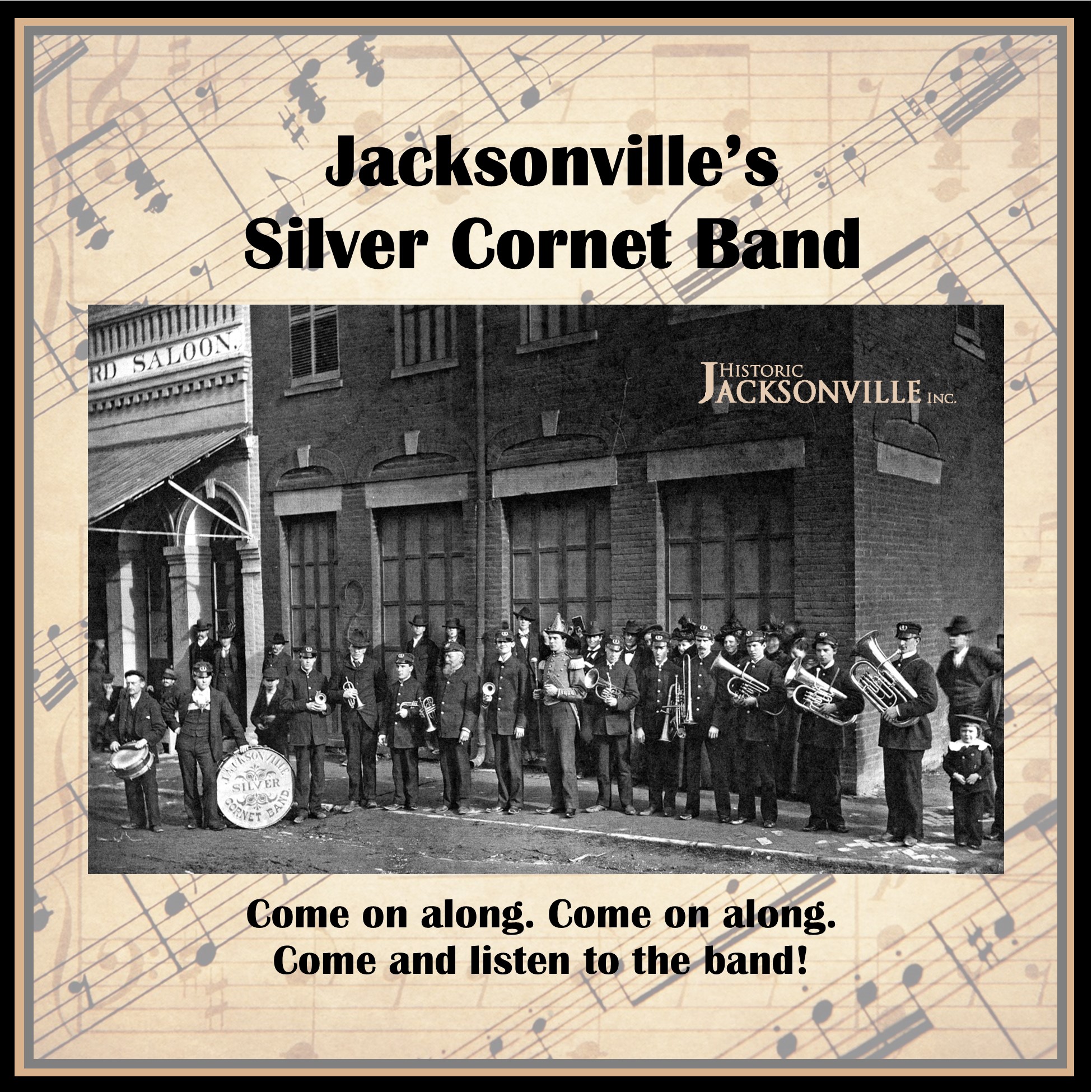

Jacksonville’s Silver Cornet Band

Music was part of Germanic culture and Jacksonville’s German speaking immigrants turned 19th Century Jacksonville into a musical culture center. Almost everyone in town owned a musical instrument, and many participated in Jacksonville’s Silver Cornet Band. The band was a popular attraction at town events and enlivened many social occasions. They even had their own band wagon which allowed them to “tour” the Valley. Members had to own their instruments, attend all rehearsals, and show up for performances.

Although the band won many contests, not all residents were fans. Someone described it as “adding a harmonious noise to the community and may have had something to do with driving the predatory wild animals out of the forest surrounding Jacksonville.”

Jacksonville’s Cannon

The mock cannon outside the Public Works shop behind Jacksonville’s City Hall serves as a tribute to the 6 pound brass field piece the Governor ordered for Jacksonville at the beginning of the Civil War. The original cannon, now housed in the Oregon Military Museum in Clackamas, was fired in honor of Union victories and on special post-war occasions. During a 1904 Grand Army of the Republic reunion, some local veterans staged their own celebration. Around midnight on Saturday, September 24, George “Bum” Neuber and some of his colleagues, under the supervision of town Marshal Bill Kenney, pulled the cannon to the middle of California Street, stuffed 6 woolen socks full of gunpowder down the barrel, and lit the fuse. The blast took out every window from 3rd to 5th streets, and left shattered doors, broken window frames, and cracked plaster in surrounding buildings. It took the local glazier 3 weeks to replace all the glass. Bum Neuber gladly footed the bill, declaring it “jolly good fun”!

The mock cannon outside the Public Works shop behind Jacksonville’s City Hall serves as a tribute to the 6 pound brass field piece the Governor ordered for Jacksonville at the beginning of the Civil War. The original cannon, now housed in the Oregon Military Museum in Clackamas, was fired in honor of Union victories and on special post-war occasions. During a 1904 Grand Army of the Republic reunion, some local veterans staged their own celebration. Around midnight on Saturday, September 24, George “Bum” Neuber and some of his colleagues, under the supervision of town Marshal Bill Kenney, pulled the cannon to the middle of California Street, stuffed 6 woolen socks full of gunpowder down the barrel, and lit the fuse. The blast took out every window from 3rd to 5th streets, and left shattered doors, broken window frames, and cracked plaster in surrounding buildings. It took the local glazier 3 weeks to replace all the glass. Bum Neuber gladly footed the bill, declaring it “jolly good fun”!

Mercy Flights

With medical care in the forefront of the news these days, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. thought it would take the opportunity to give a shout out to Mercy Flights – our regional air and ground ambulance service and the nation’s first non-profit air ambulance. It was founded in 1949 by George Milligan, a Medford air traffic controller, after a friend died of polio, unable to survive the long, slow drive to Portland. Mercy Flights added ground transportation in 1992, creating a regional medical transportation network. Normal ambulance service can be expensive–$1,200 or more for ground; $20,000+ for air. Mercy Flights offers membership subscriptions that accept any insurance you have as payment in full and discounts costs by 50% for those without insurance. Jacksonville’s own Mike Burrill, Jr. is currently serving as Mercy Flights interim CEO. Mike has been a Mercy Flights board member for 12 years and board chair for 6, following his father and grandfather in Mercy Flights service. We’ve come a long way since 1851 when Jacksonville boasted the first ambulance service west of the Rockies!

Old Stage Road

Have you ever wondered about the names “Old Stage Road” or “South Stage Road” for the streets leading north and south from Jacksonville? Well, you can’t have stage service without roads. Regular stage service for the area did not begin until the mid-1850s and the stops were Ashland, Jacksonville, and Rock Point (near Gold Hill).

The route to Yreka was not a road; it was a rough and difficult passage best made on foot or horseback. The Siskiyou Mountain Wagon Road, a toll road and the first “engineered” road over the mountain crest that separates California and Oregon, did not open until August 1859.

Stages could now run from Sacramento, California, to Portland, Oregon. The stage and freight companies carried passengers at a charge of 12½¢ per mile. Freight was hauled for 4¢ per pound, in large, heavily built wagons. What made the service profitable was a lucrative contract to carry the U.S. Mail. This 710-mile route was the second longest stage run in the U.S.

So why the strange 90 degree turns in the road? If a land claim holder refused permission to pass through his property, the road had to go around it.

Although pack trains occasionally carried passengers, the stage and freight wagons were the principal methods of transportation and passenger travel until 1884, when the railroad entered the Rogue River Valley. With completion of the railroad over the Siskiyous, the last stagecoach traversed the pass on December 18, 1887, the day following the official Golden Spike ceremony in Ashland.

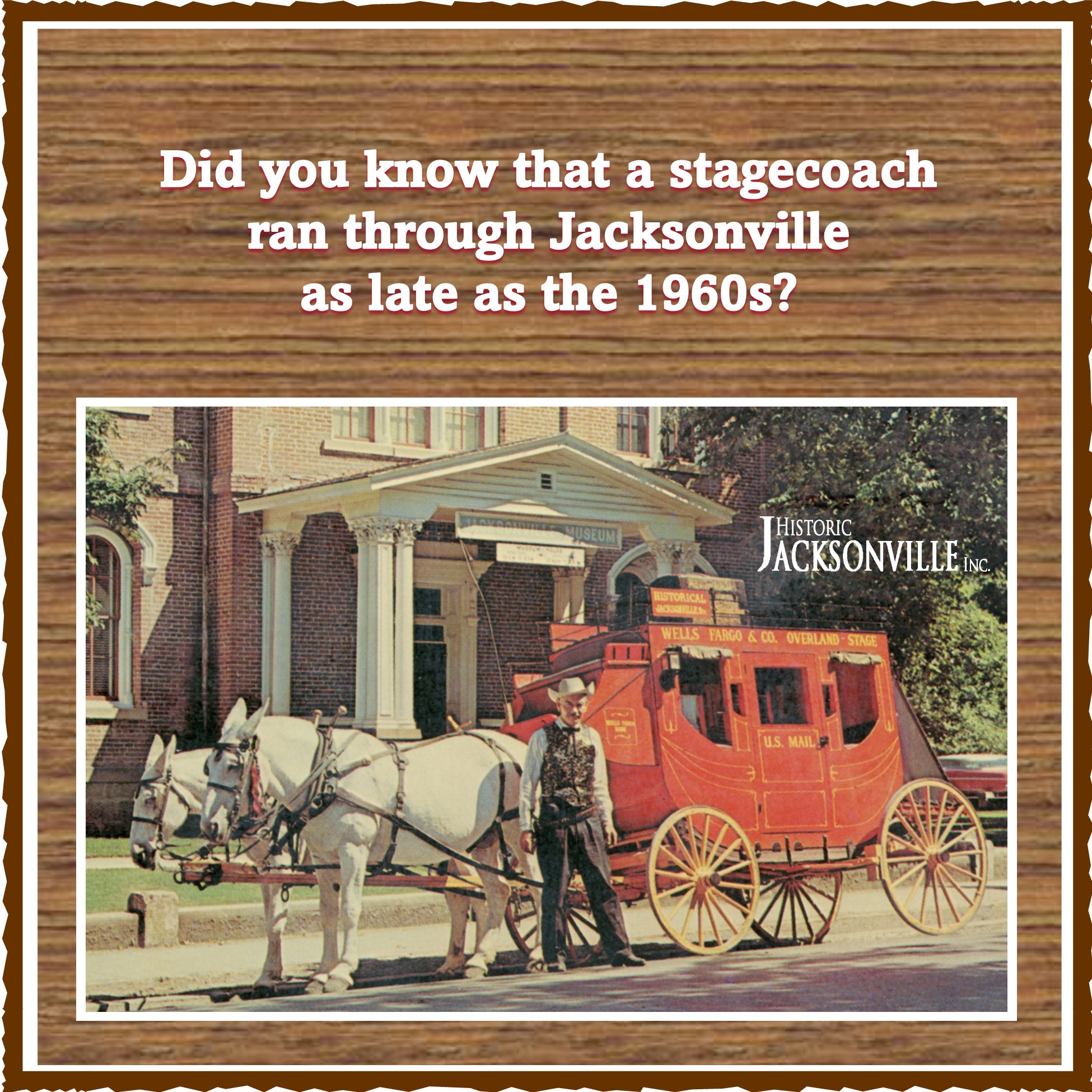

Stagecoach

Before the Jacksonville Trolley began offering narrated history tours, visitors and residents alike could board a stagecoach operated by George McUne for a 15-minute tour of the town. After traveling in a covered wagon from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon as part of Oregon’s 1959 Centennial Wagon Train, McUne had sent to the Smithsonian for original Wells Fargo stagecoach plans and handcrafted a replica. In 1961, he began offering stagecoach tours of Jacksonville. The coach carried 12 to 15 passengers and was drawn by his reliable mules, Fibber and Molly. McUne would share stories about the discovery of gold, President Hayes’ visit to Jacksonville, the West’s last great train robbery, and other local tales. And tours always included a robbery at the Beekman Bank. McUne’s stagecoach rides were the genesis of what became Jacksonville’s original Pioneer Village with its array of “rescued” historic buildings and its multiple attractions.