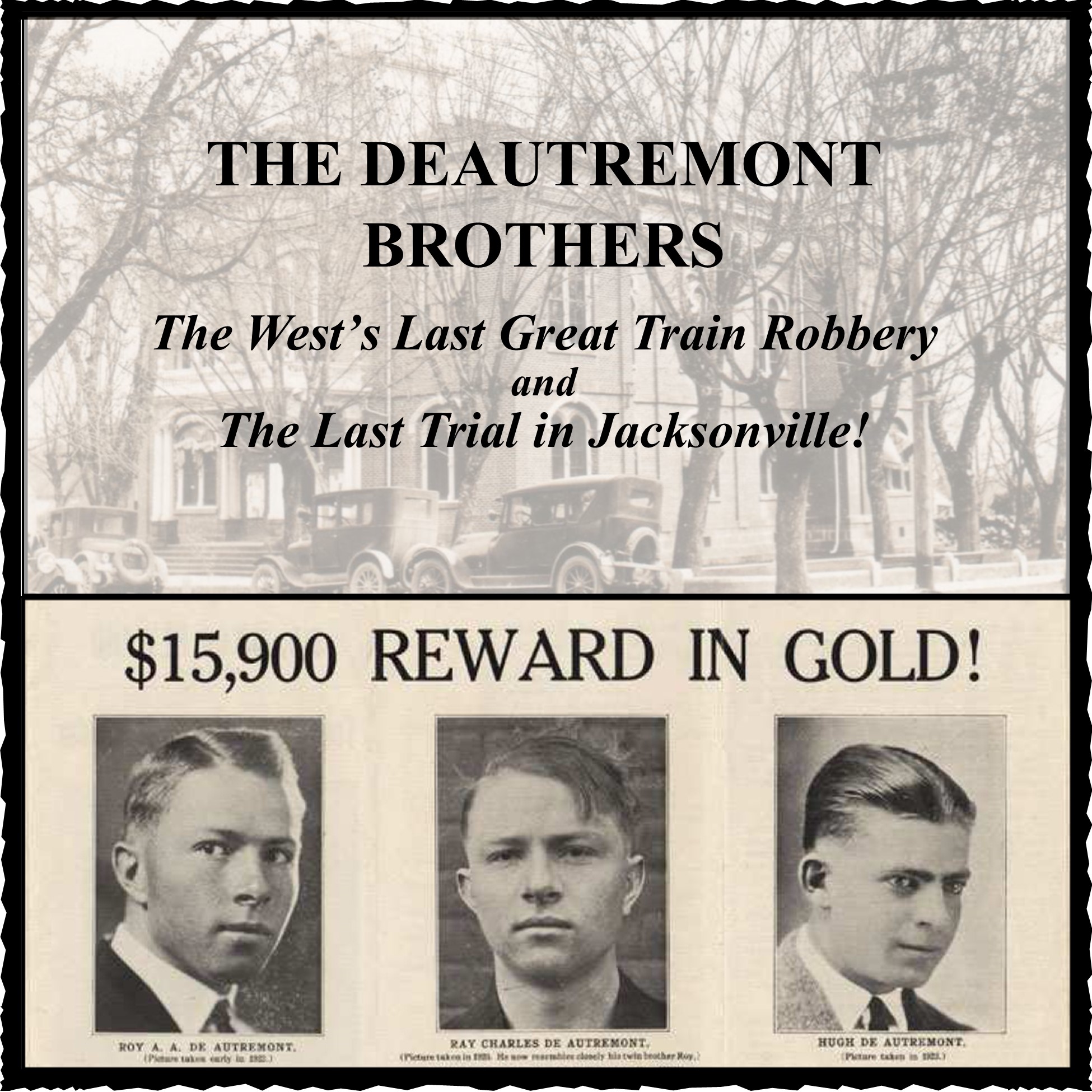

Deautremont Brothers

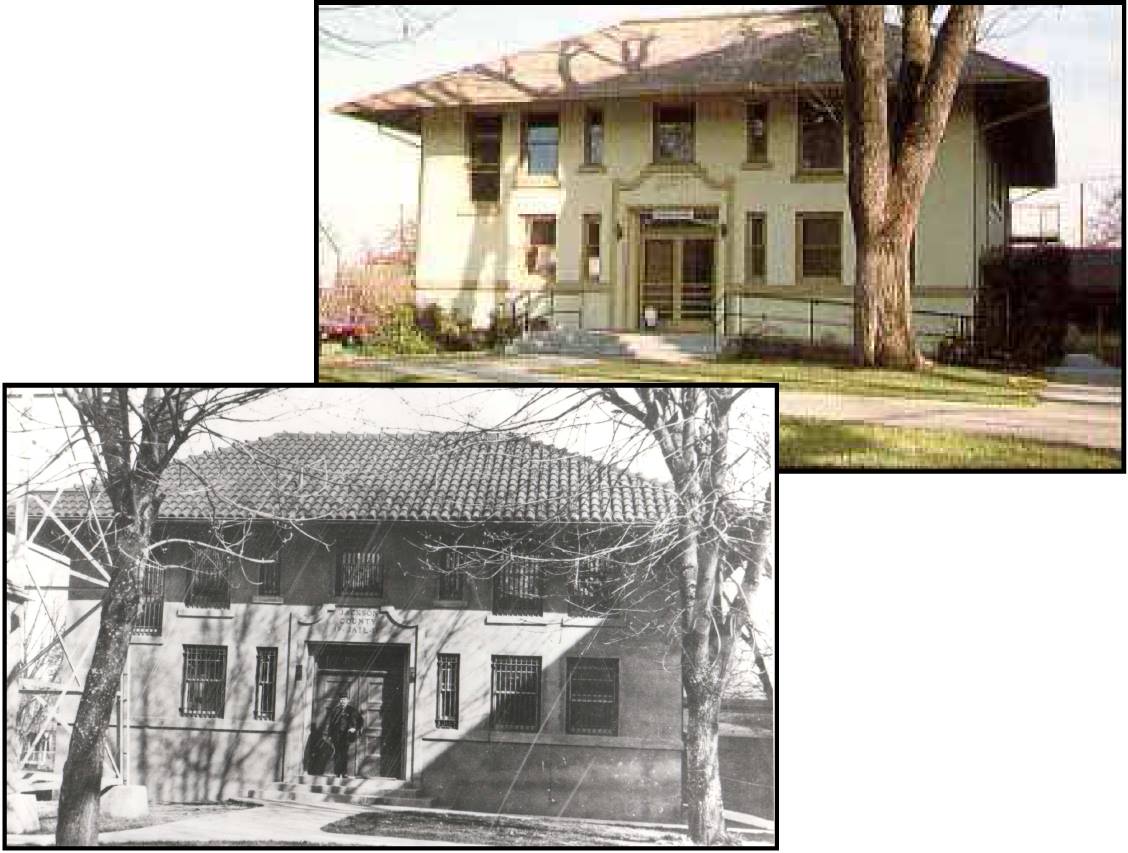

When the historic 1883 Jackson County Courthouse, located on Jacksonville’s North 5th Street Courthouse Square, was completed, it was declared “the crowning glory of Jacksonville.” However, this “crowning glory” was almost “too little, too late” after the railroad by-passed Jacksonville in favor of the flatter Valley floor. But Jacksonville and the historic Courthouse had one last glory moment in 1927 when the trial of the DeAutremont brothers attracted nationwide attention. After a three-year manhunt that extended into Mexico, Canada and Australia, the three DeAutremont brothers were apprehended and charged with the murder of four railroad employees during a 1923 holdup in railroad Tunnel 13 in the Siskiyou Mountains. Billed as the West’s last great train robbery, this was the final trial held in the courthouse before all legal business was moved to the new county seat of Medford and its newly erected courthouse

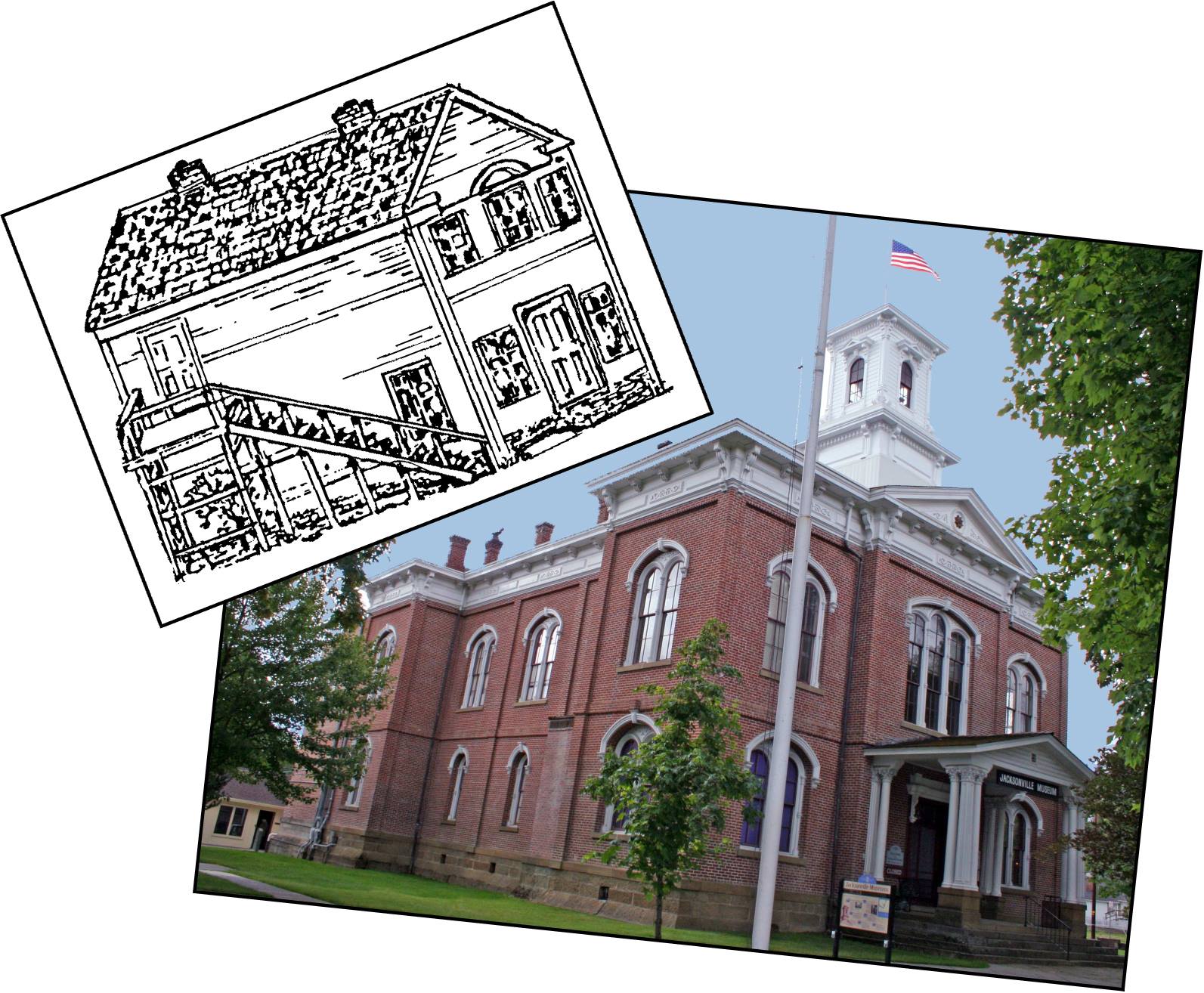

Jackson County Courthouse #1

The first Jackson County Courthouse erected on Jacksonville’s Courthouse Square on North 5th Street was a 2-story clapboard structure dedicated March 6, 1859, by the Warren Lodge No. 10 of Free and Accepted Masons as a Masonic Hall. Shortly afterwards, the Masons leased the first floor to the County for court use. For 6 years previously, court proceedings had been held in various town structures including the New State Hotel and the Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1867, the Masons relinquished their 2nd floor space to the Jackson County Commissioners and for the next 15 years, the County’s first Courthouse was used not only by the commissioners, judges, and county officials, but also by private local lawyers.

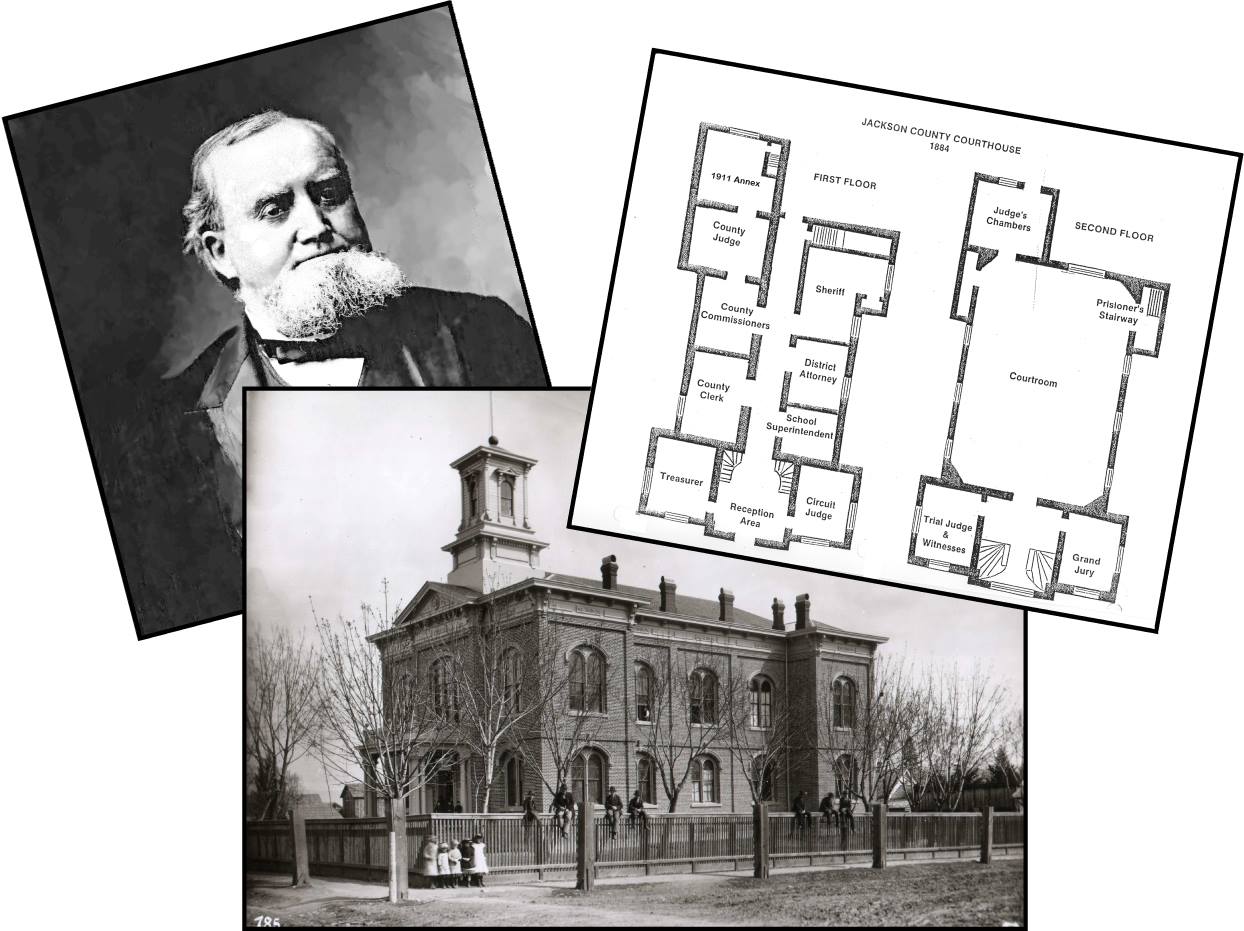

Jackson County Courthouse #2

Within 12 years of its erection in 1859, the first Jackson County Courthouse on North 5th Street in Jacksonville was being called “dilapidated” and “a disgrace to the county,” and in 1880 a grand jury condemned it. It still took another 3 years for the County Commissioners to take action, draw up plans and select a builder. Prodded by Judge Silas Day, the Commissioners determined that they wanted a 2-story brick structure, 92 x 60 feet, with 14 foot ceilings. The cornerstone was laid on June 23, 1883. By August the brick walls were raised, by September the cupola was completed, and the court convened for the first time on February 11, 1884.

Jackson County Courthouse #3

Even before it was completed, the historic Jackson County Courthouse, located on Jacksonville’s North 5th Street Courthouse Square, was being called one of the “most prominent buildings in Jacksonville” and “very ornamental.” Upon completion, it was declared “the crowning glory of Jacksonville.” However, this “crowning glory” was almost “too little, too late” after the railroad by-passed Jacksonville in favor of the flatter Valley floor. Even a spur line connecting Jacksonville to the new Southern Oregon hub of Medford only postponed the town’s ultimate decline…but ensured its preservation.

Jackson County Jail – 1875

One of our trivia fans asked about the Jackson County Jail pictured in “The Last Hanging in Jacksonville.” The jail shown, constructed in 1875, was the second jail on Courthouse Square. It was described as a sturdy brick building reinforced with “4,000 pounds of iron spikes for strength.” Seven inch thick wooden planks lined the masonry walls and separated the cells. The building burned to the ground in 1889 on a night when the sheriff had chosen to “sleep” at the U.S. Hotel instead of the jail. The fire took the lives of the jail’s three inmates, one of whom was scheduled for release the following day.

Jackson County Jail

Three previous jails stood on the site of the historic Jackson County Jail located at 216 North 5th Street in Jacksonville. In 1875, a sturdy brick jail replaced a simple wooden structure built in the 1850s. When the new jail burned in 1889, it was replaced with a larger building boasting a concrete floor and corrugated iron ceiling. By 1910 it was deemed old and inadequate and was torn down to make way for the current structure. Completed in 1911, the existing jail was built to house 25 prisoners. Heavy iron cages lined the first floor; reinforced cells and padded cells were on the second floor. The jail continued in service until the county seat was moved to Medford in 1927. Today the facility houses Art Presence art center.

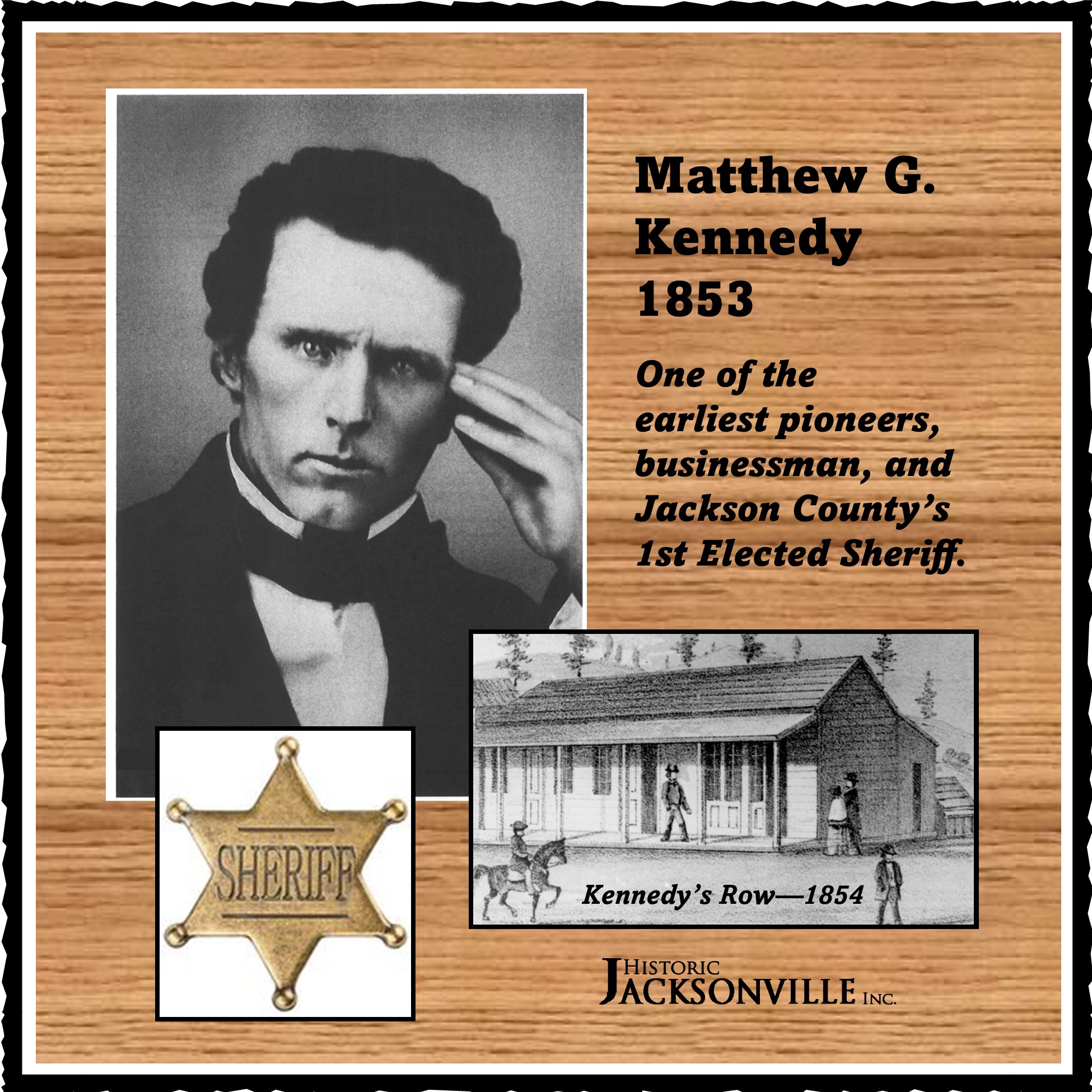

Matthew G. Kennedy

We’re back to our series of Jacksonville “firsts.” This time Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is highlighting one of the Valley’s earliest pioneers, Mathew G. Kennedy. Kennedy had arrived in “Table Rock City” in 1852—at the time little more than a rowdy mining camp. In early 1853, he was appointed town constable at the ripe old age of 23 and became the first elected Sheriff of Jackson County later that year.

However, that was not the only “first” to Kennedy’s credit. Kennedy was the first Jacksonville settler to record his claim to a 100-foot frontage on the north side of California Street. Around 1854, he constructed 1 or 2 wood frame buildings that housed an “assemblage of shops” known as “Kennedy’s Row.” That site now houses The Pot Rack, The Blue Door Garden Store, Farmhouse Treasures, and the historic Beekman Bank Museum. Early newspapers carry advertisements for Kennedy Tinware (a hardware store) at what is now 150 W. California (The Pot Rack).

Kennedy sold his tin shop to Love and Bilger in 1856, and a year later left Jacksonville to build a hotel called the Metropolitan House Hotel in Yreka. By 1863, he had moved on to San Francisco.

However, Kennedy’s house still stands at 240 North 3rd Street. Constructed in 1855, it’s the oldest Jacksonville residence still standing!

Jackson County Poor Farm

Today we’re also asking for your help with a history mystery! We’re trying to locate Emil DeRoboam’s Jackson County Poor Farm. [See photos.] We recently told you how Emil DeRoboam was the farm’s superintendent. He apparently took over from his aunt, Madame Jeanne DeRoboam Holt, proprietress of the U.S. Hotel. She had obtained the contract for the county “poor hospital” in 1880, housing the indigent for $1.49 a day in a building she rented adjacent to her Franco-American Hotel, the current site of the Jacksonville Inn cottages. Emil apparently ran it for two years after her death in 1884. When he moved his family to Yreka, the inmates were relocated to J.M Lofland’s farm near Jacksonville. However, by 1888, Emil was back in town and purchased the 642-acre Bellinger land claim. In addition to farming the land, he obtained the contract for the county “poor farm” in his own right and ran it for almost 20 years until the county purchased a site near Talent. The Talent site, which operated until 1983, is now home to the Southern Oregon Educational Service District. But back to Emil. Where was his “poor farm”? It had to be somewhere near Bellinger Lane and his home at 3995 S. Stage Road. Can you help us locate it?

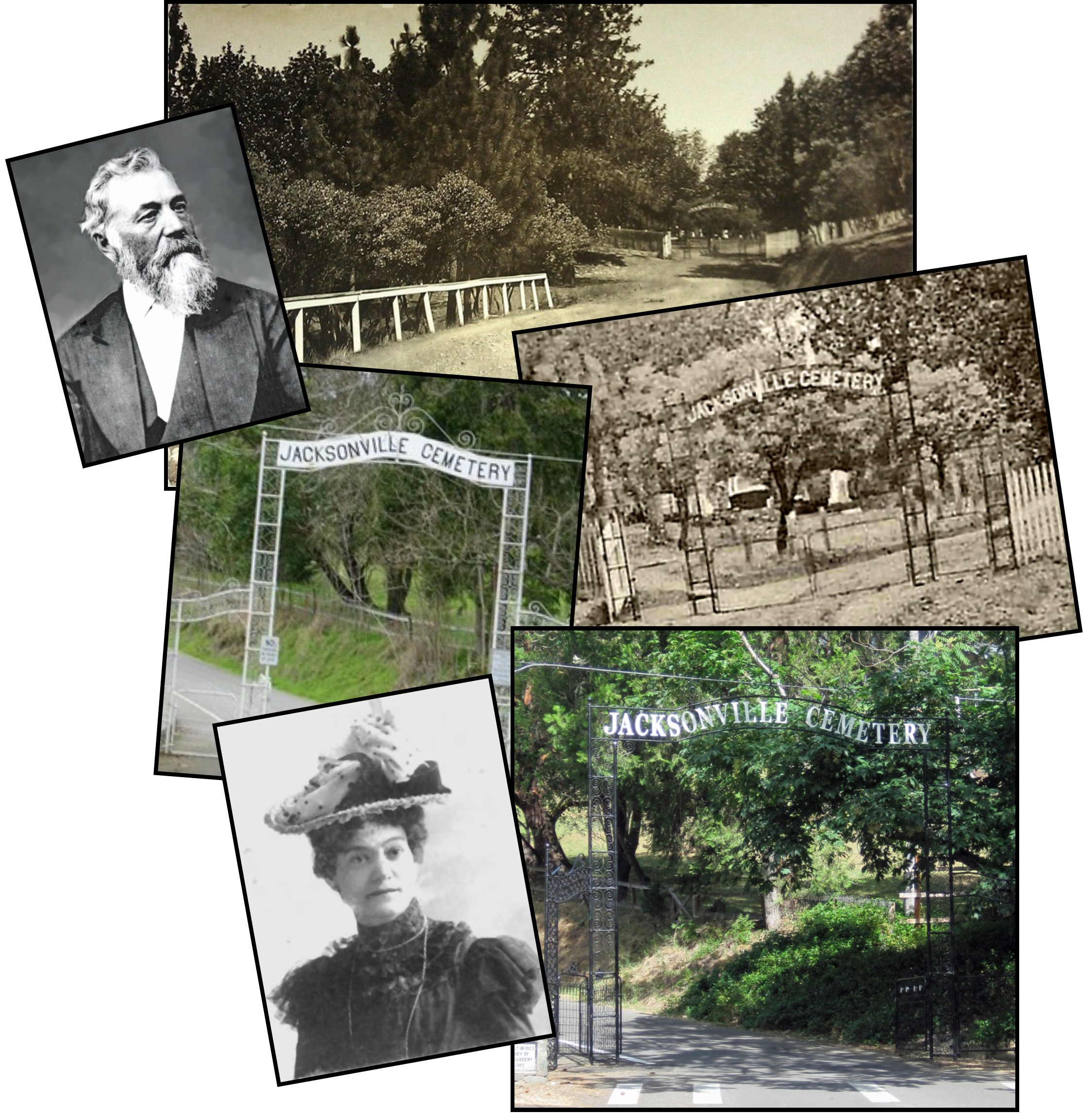

Jacksonville Historic Cemetery#1

Have you had a chance to admire the new gate to Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery on West E Street? Installed in the fall of 2018, the new gate’s white lettering and black wrought iron replicates the original gate erected about the time the cemetery officially opened in 1860. When James Napper Tandy Miller set aside the original acreage for a town cemetery in 1859, he required the cemetery to be fenced to protect against the intrusion of wild animals. But when the cemetery opened, the gate was at the top of the hill! The dirt access road (now Cemetery Road) that led to the entry presumably followed an old Indian trail. In 1923 Alice Applegate Sargent funded the Cemetery Road wall in memory of her husband, Col. Herbert Howland Sargent. Around the time the wall was built, the original cemetery gate was replaced, and the entry relocated to the bottom of the hill. The 2018 gate replaces the familiar white iron gate erected in the early 1900s. The Jacksonville cemetery is one of the oldest pioneer cemeteries in the Pacific Northwest and has remained in continuous use since its founding. Join the Friends of Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery for guided tours, evening strolls, workshops, and their annual “Meet the Pioneers” event.

Jacksonville Historic Cemetery#2

We jumped ahead of ourselves yesterday, but today really is History Trivia Tuesday! There are enough historic myths going around without Historic Jacksonville, Inc. adding to them, so we want to correct our June 18th post about the gates to Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery on West E Street. The cemetery’s Friends were kind enough to give us the true “skinny.” When James Napper Tandy Miller set aside the original cemetery acreage in 1859, he did require the cemetery to be fenced. A white picket fence was erected at the top of Cemetery Hill, but the original gates were probably wood. At some point the wooden gates were replaced with the familiar metal arch and gates. Photos show they were there no later than 1912 but did not date to the cemetery’s official opening in 1860. Later the original metal arch and gates were moved to their current location at the bottom of the hill—possibly in 1923 in conjunction with Alice Applegate Sargent funding the Cemetery Road wall in commemoration of her husband. Pieces were subsequently added to the arch and gates to increase their height and width, allowing motorized vehicles to pass through and under. The arch and gates that now sit at the entrance to the cemetery are the same arch and gates that originally sat at the top of Cemetery Road. In 2018, the City of Jacksonville paid for them to be restored to their original color and state—with one exception. The side pieces were angled to increase the structure’s stability, allowing an increase to the width of the entry of one of the oldest pioneer cemeteries in the Pacific Northwest.

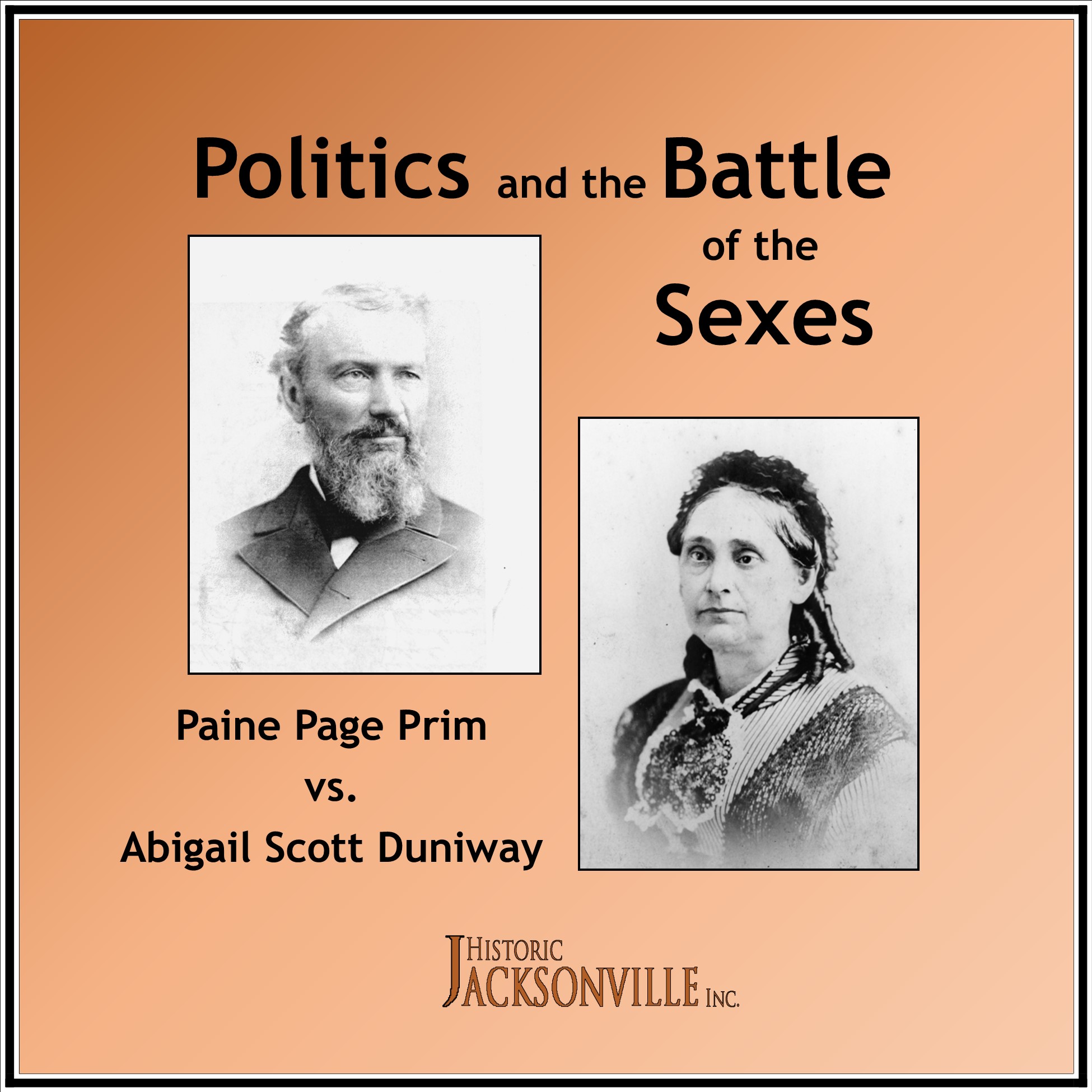

Jacksonville Politics

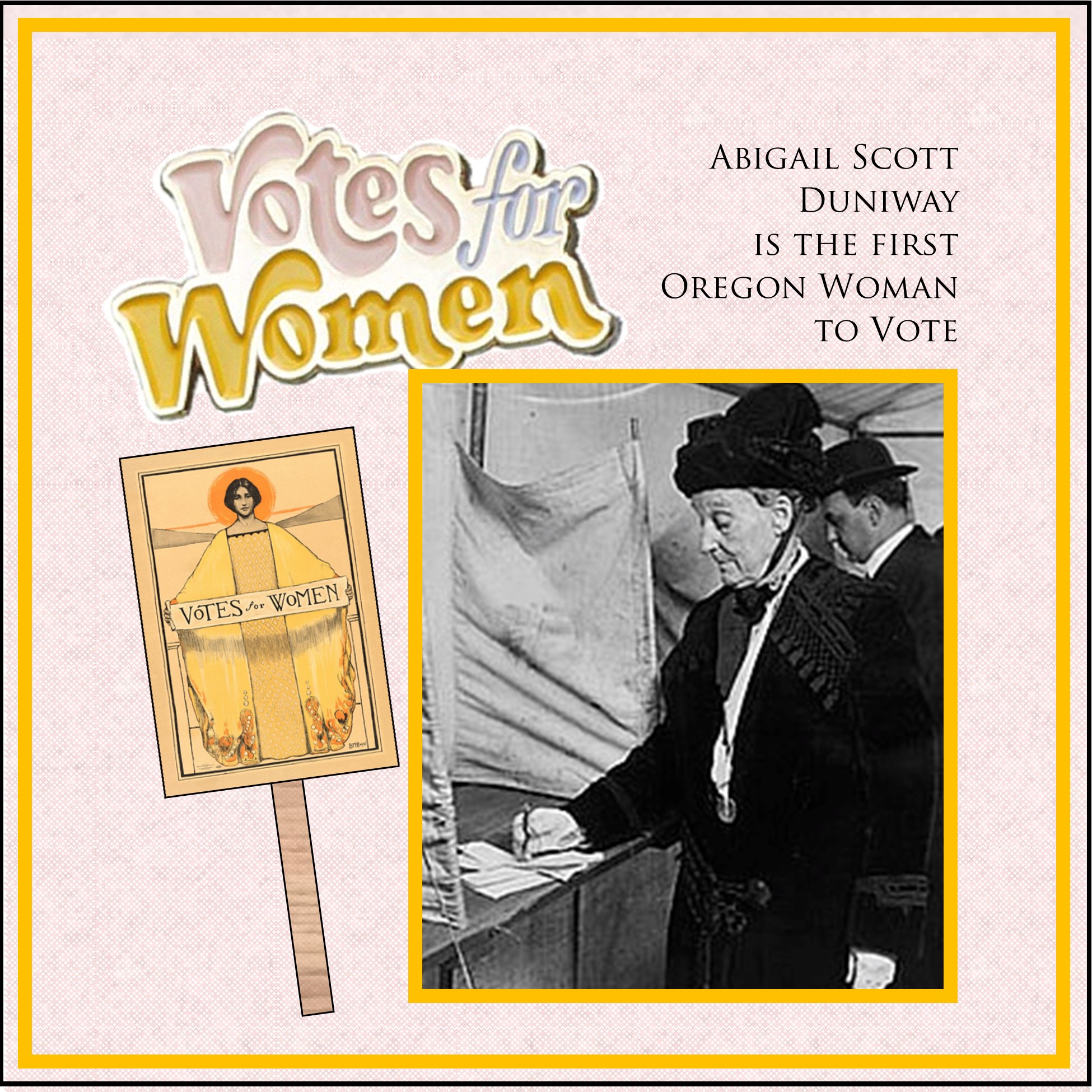

Jacksonville residents are usually so civil that we can’t imagine men “egging” a lady and burning her in effigy, but that was the case when Abigail Scott Duniway campaigned for women’s suffrage in Jacksonville in 1879. Her offense was unearthing the past marital difficulties of one of the town’s most prominent citizens, Judge Paine Page Prim. She wrote scathingly in her newspaper, the New Northwest about Judge Prim having abandoned his wife, even though he and his wife had reconciled years before. The editor of the Democratic Times wrote: “If these are the teachings of woman suffrage, it should be prohibited by statute.” Prim in turn prevented her from speaking at the region’s Fourth of July celebration.

Duniway admitted in her autobiography, Path Breaking, that she was partly to blame for the incident, but dismissed the Jacksonville men as “old miners, or refugees from the bush-whacking regions of Missouri, whence they had been driven by the exigencies growing out of the Civil War.” But she also presented a more forgiving face writing that Jacksonville had become the “center of a large degree of Equal Suffrage sentiment.” Aside from her one unfortunate experience, she said she was always made to feel at home here.

And Abigail eventually won the “battle of the sexes.” After five previous attempts, Oregon gave women the vote on November 12, 1912, the 9th state to do so, and 8 years prior to the passage of the 19th Amendment.

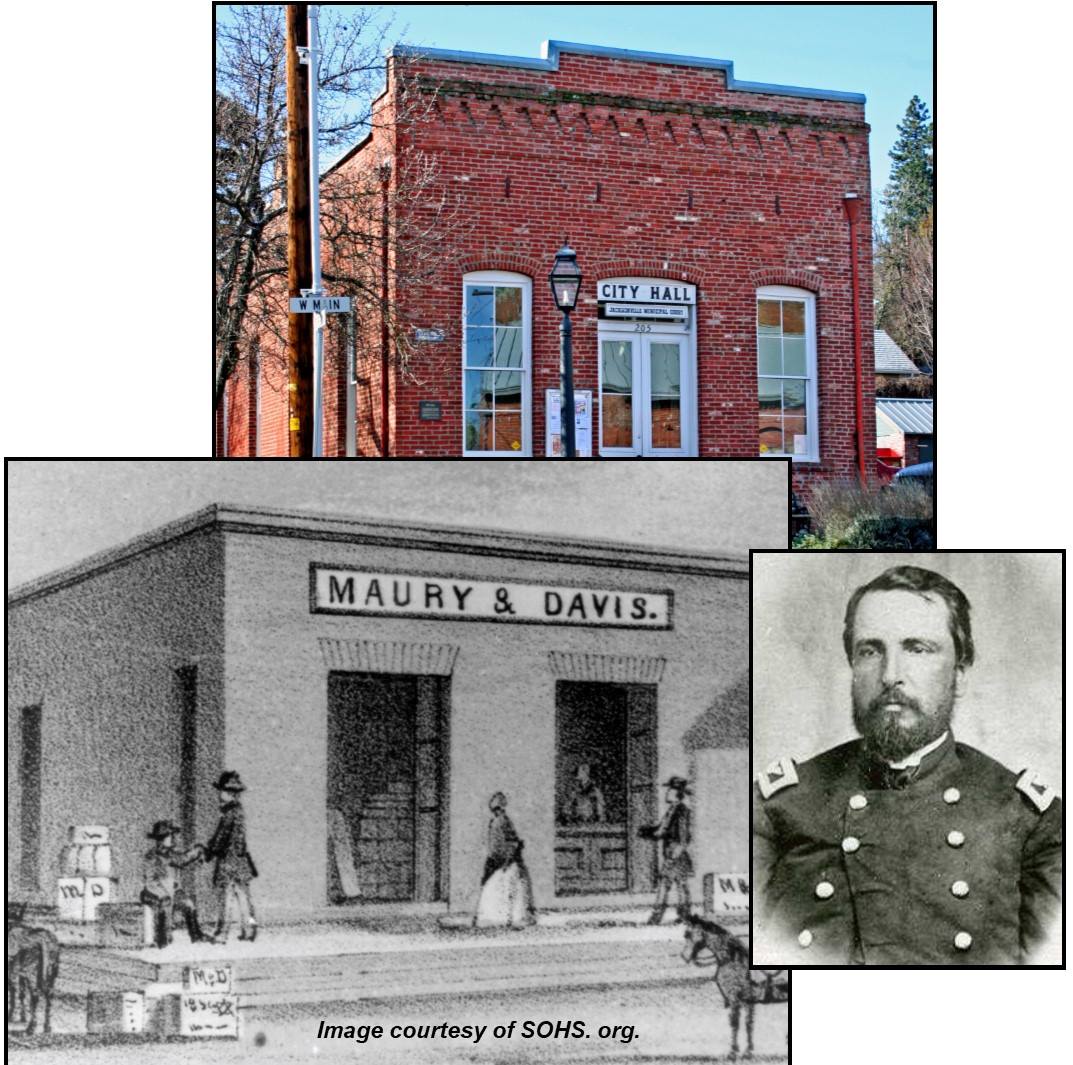

Jacksonville’s Old City Hall

Jacksonville’s 1880 Old City Hall is the oldest government building in Oregon to remain in continuous use. It stands at the intersection of S. Oregon and Main streets, the heart of Jacksonville’s original business district, on the site of the 1st brick building in town–the 1854 Maury & Davis Dry Goods store. Reuben Maury and Benjamin Davis had run a very successful general merchandise building at this location until 1861. Their partnership ended with the outbreak of the Civil War when Maury became an officer in the Union Army; Davis, a nephew of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, was claimed by family ties. Various enterprises occupied the original building until a fire in October 1874 gutted the interior. The burnt-out building sat empty until the Jacksonville’s Board of Trustees purchased the site for a town hall. Bricks from the original store were recycled into the current building’s construction. Completed in 1881, Jacksonville’s Old City Hall still hosts City Council meetings, City commissions and committees, municipal court, various community organizations, and monthly movie nights.

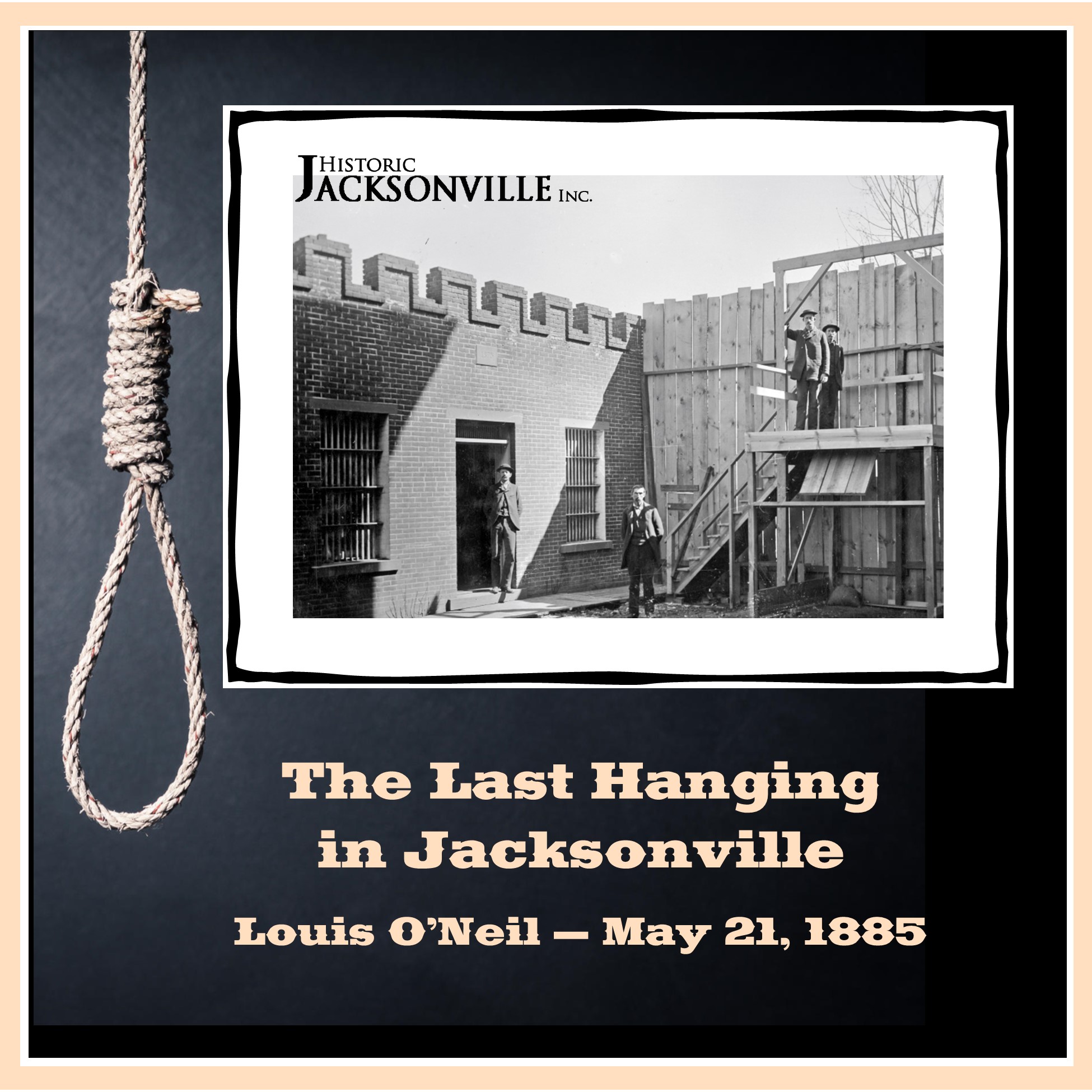

Last Hanging in Jacksonville

In 1885, scarcely a year after the historic Jackson County Courthouse was completed, it was christened by one of the most notorious events to take place in town—the trial and execution of Louis O’Neil. O’Neil, who had been having an affair with Mrs. Mandy McDaniel, was found guilty of the murder of her husband. An appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court only intensified public interest. The gallows were erected between the courthouse and the jail, screened by a 16-foot-high fence and guarded by the Jacksonville Fire Department. The execution was witnessed by 200 men, women, and children, the “lucky” ticket holders for the event. O’Neil was the last person hung in Jacksonville; his body is interred in the County pauper section of the Jacksonville Cemetery.

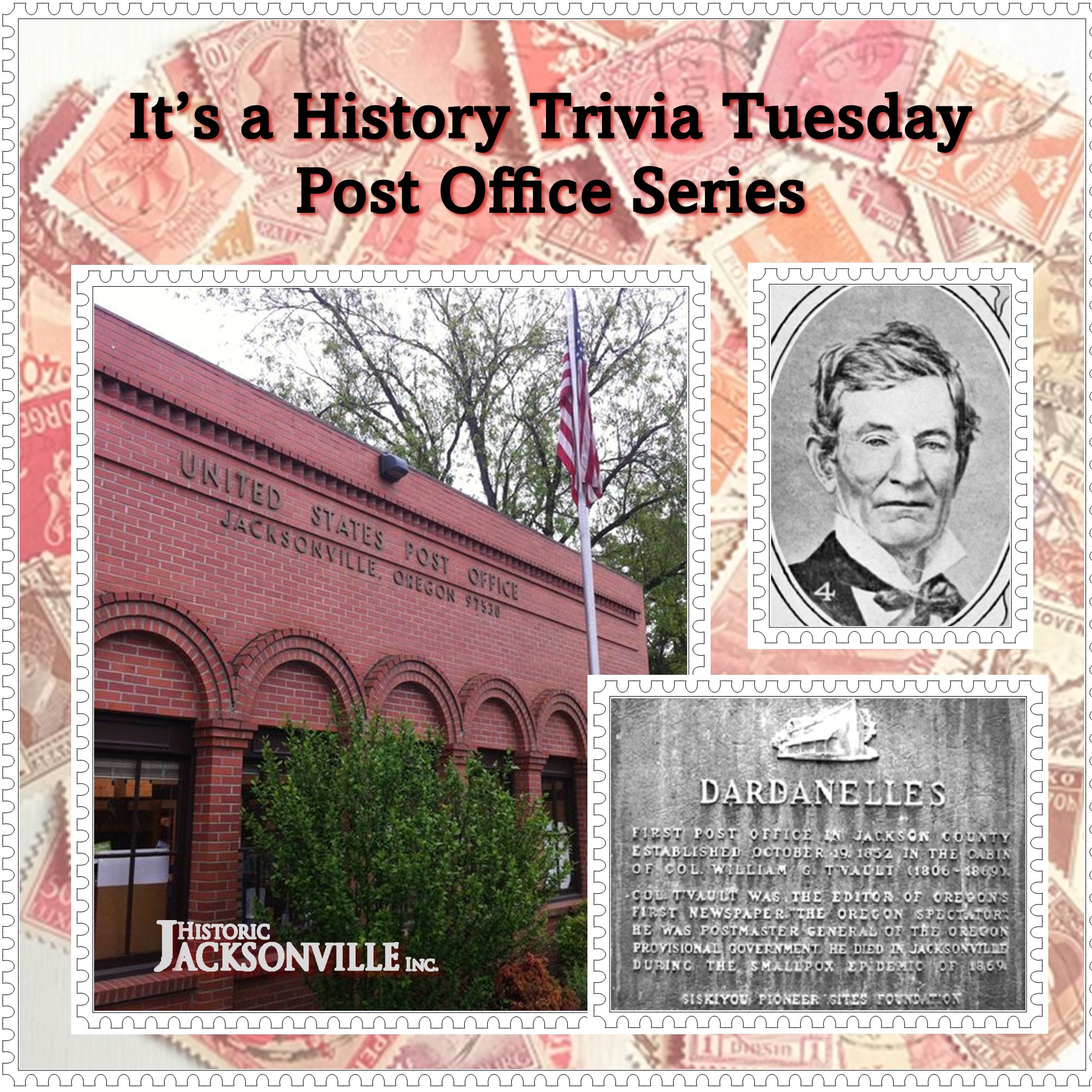

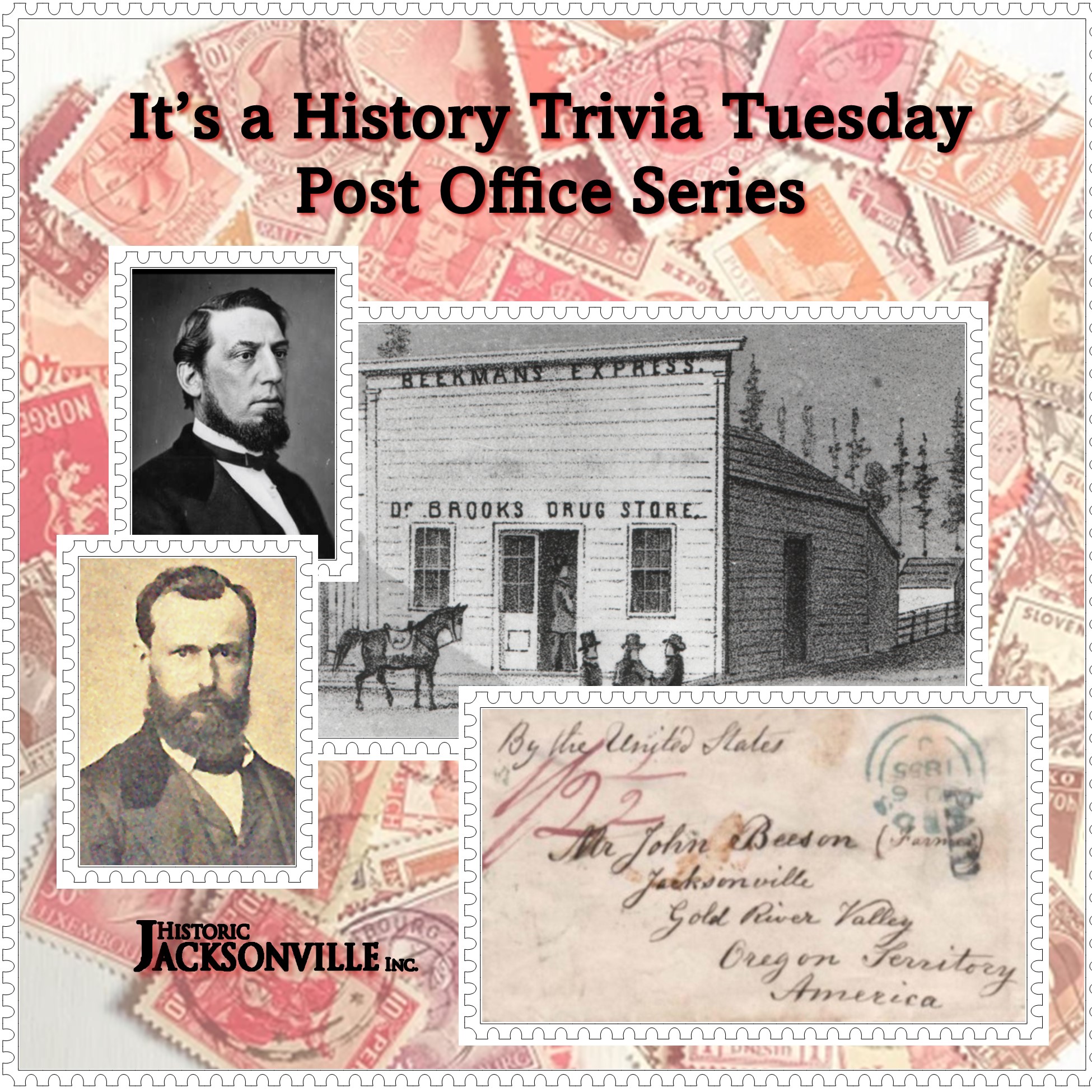

Post Office #1

Did you know that the Jacksonville post office is the only independent post office in Jackson County with its own superintendent—a story all to itself. And it’s the oldest continually operating post office in the county since opening in 1854. It’s been located in almost every building in Jacksonville’s historic downtown. With mail now being sent to Portland for processing and people concerned about mailed in ballots in the upcoming election, for the next History Trivia Tuesdays Historic Jacksonville, Inc. will be tracing as much local post office history as we’ve been able to piece together.

The first Jackson County post office was established by William T’Vault in 1852 in the Dardanelles, across the Rogue River from Gold Hill. T’Vault, who founded the now defunct town, was Oregon’s first postmaster general, being named to that position in 1845 soon after the wagon train he commanded reached Oregon City.

T’Vault came to Southern Oregon in 1852 when he learned of the region’s gold strikes. He moved to Jacksonville in 1855, establishing the first newspaper in Southern Oregon, the Table Rock Sentinel, changing its name to the Oregon Sentinel 3 years later.

He also returned to his law practice, and in 1858 was elected to the Territorial Legislature as a slavery and states rights advocate, soon after becoming speaker of the House. He was an early advocate of the “state of Jefferson,” which he pictured as an independent Pacific slave-holding republic. His vision has yet to be realized. T’Vault died in 1869, the last victim of the 1868-1869 smallpox epidemic.

Post Office #2

The first “post offices” on the West Coast were essentially contracts with individuals or businesses who were authorized to handle the mail and deliver it along a designated route. Individuals were usually “express riders”; businesses were typically stage companies; and the “post office” was probably the express office or stage stop. Mail might be addressed to a general area and could turn up at any local “post office,” so individuals making trips to town might ask for mail for all their neighbors.

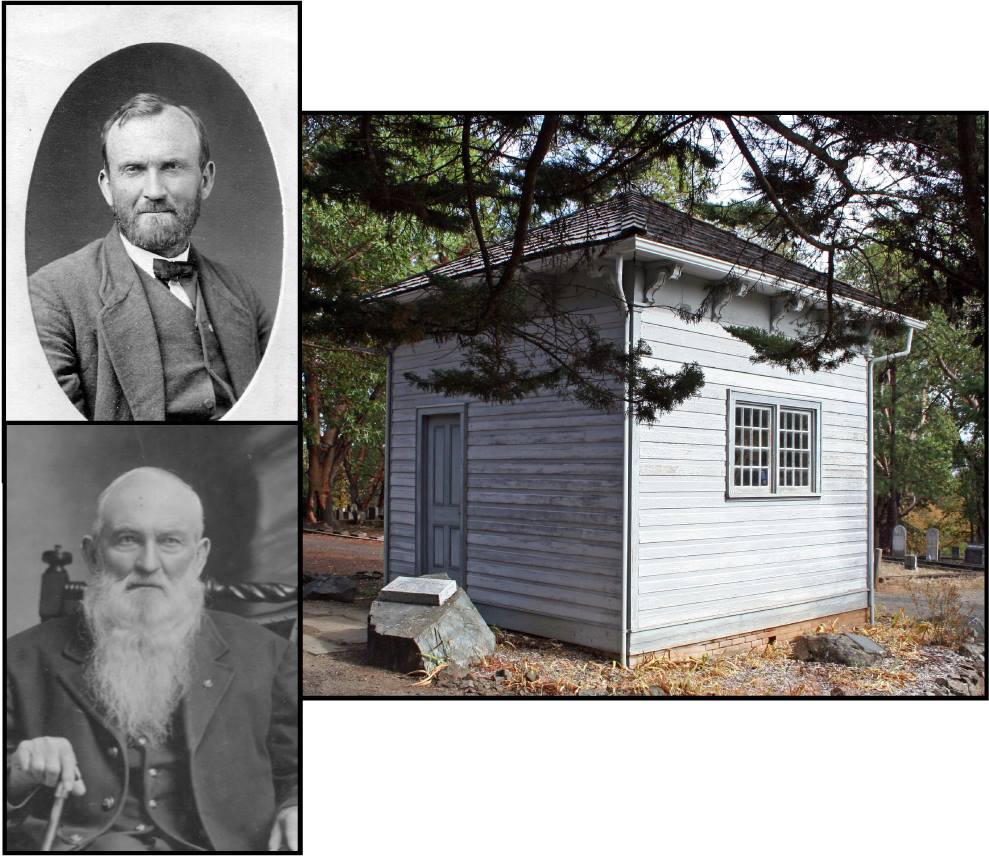

R. Dugan opened the first Jacksonville post office on February 18, 1854. Sam Taylor (lower left) succeeded him as postmaster in December of that year. Taylor was a miner and early Jackson County Deputy Sheriff. C.C. Beekman (upper left) then carried the mail from Jacksonville to Yreka until 1863, initially as an express rider for Cram Rogers & Company, then for his own company, Beekman’s Express.

The U.S. didn’t issue postage stamps until 1847, and for a number of years afterwards, letters could still be hand stamped. Prepayment of postage was not required until 1855. From 1851 to 1855, a prepaid ½ ounce transcontinental letter cost 6₵; the unpaid rate was 10₵. The prepaid West Coast rate was 3₵ and the unpaid rate 5₵. The mail contractor would have added a surcharge of 1₵ or 2₵ per letter.

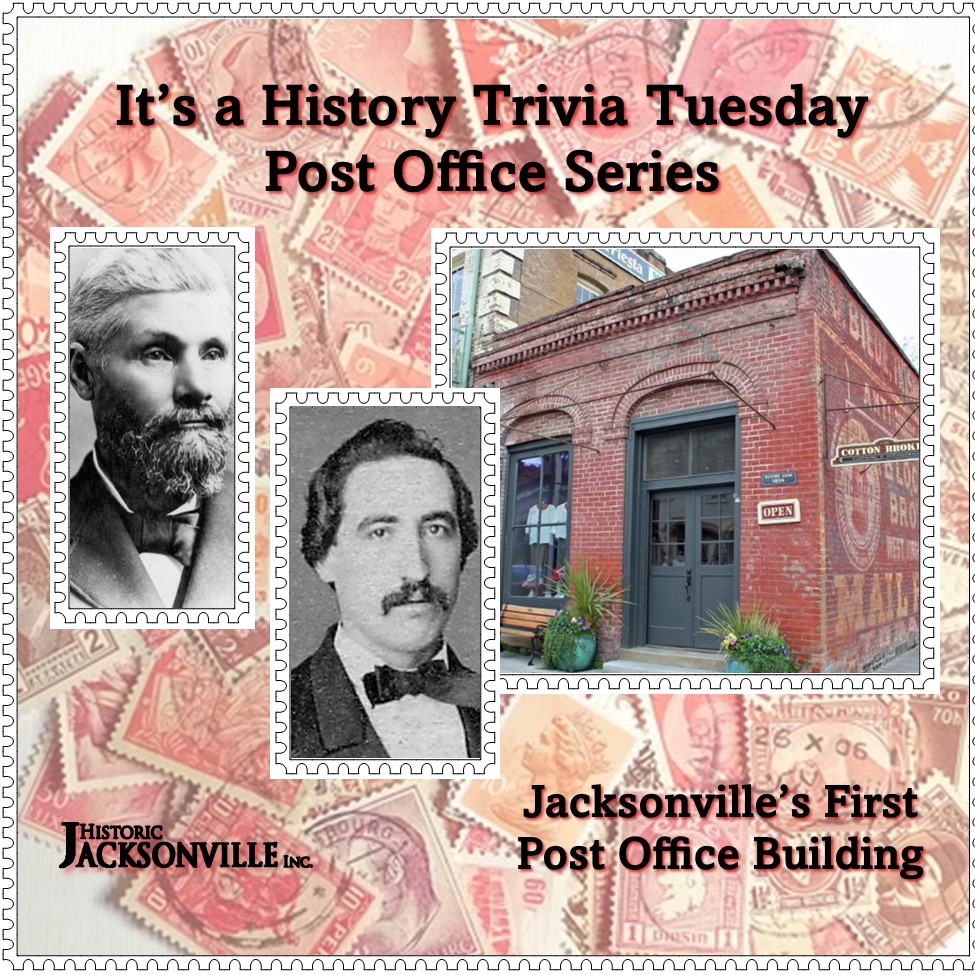

Post Office #3

For the next few weeks we’re continuing to track the history of the Jacksonville post office, the oldest operating post office in Jackson County. Supposedly the first actual Jacksonville post office building of record was the brick building at 110 S. Oregon Street that now houses the Cotton Broker.

In 1861, Israel Haines (shown top left) and his brother Robert constructed this 1-story brick building at the corner of California and Oregon streets, replacing a wooden building they had occupied since arriving in Jacksonville 7 years earlier. It’s one of the oldest commercial buildings to survive 3 major fires that ravaged the town. In 1864 it reportedly housed the Jacksonville post office.

The construction expense may have overextended the brothers financially, since post-1866 records show a series of short-term occupants—Isadore Caro, Gustav Karewski, and Jeremiah Nunan. By 1872, Max Muller (lower left) had moved his “groceries, candies, nuts, and stationery” store to this location where he also performed the duties of postmaster.

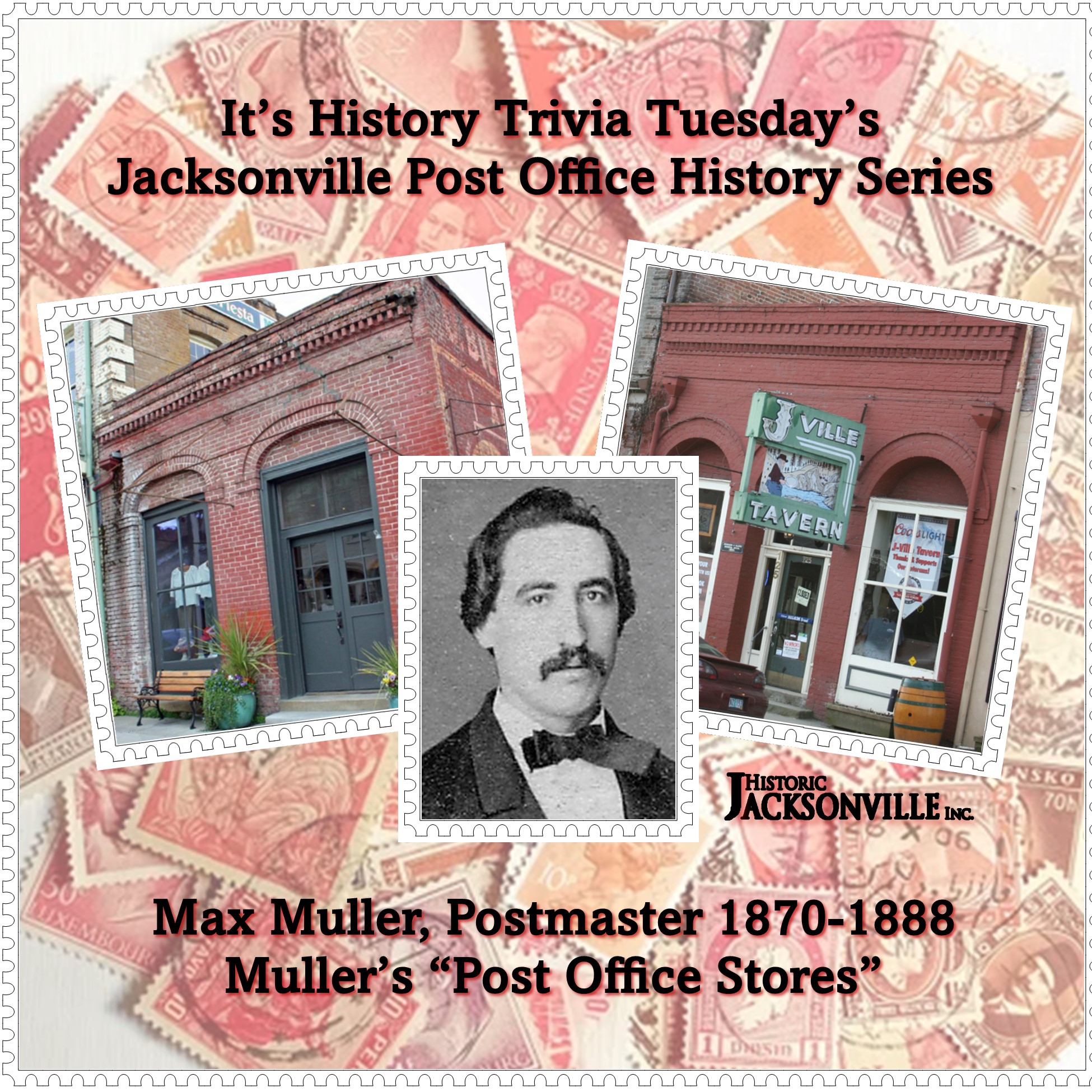

Post Office #4

Continuing our saga of Jacksonville’s post office, in 1870, Max Muller was appointed postmaster of Jacksonville. As well as an honor, this was a good business opportunity. For the next 18 years Muller served as postmaster and his place of business was known as the “post office store.” Initially the post office was in the Muller & Brentano “groceries, candies, nuts, and stationery” store at the corner of California and Oregon, now home to the Cotton Broker.

At some point after the fire of 1874, Muller & Brentano moved to 125 W. California, now occupied by the J’ville Tavern. This location became the “new” Post Office Store until 1888. After that it became “Max Muller & Co., Jacksonville, Or., the Leading Dealers in Gents Furnishing Goods.”

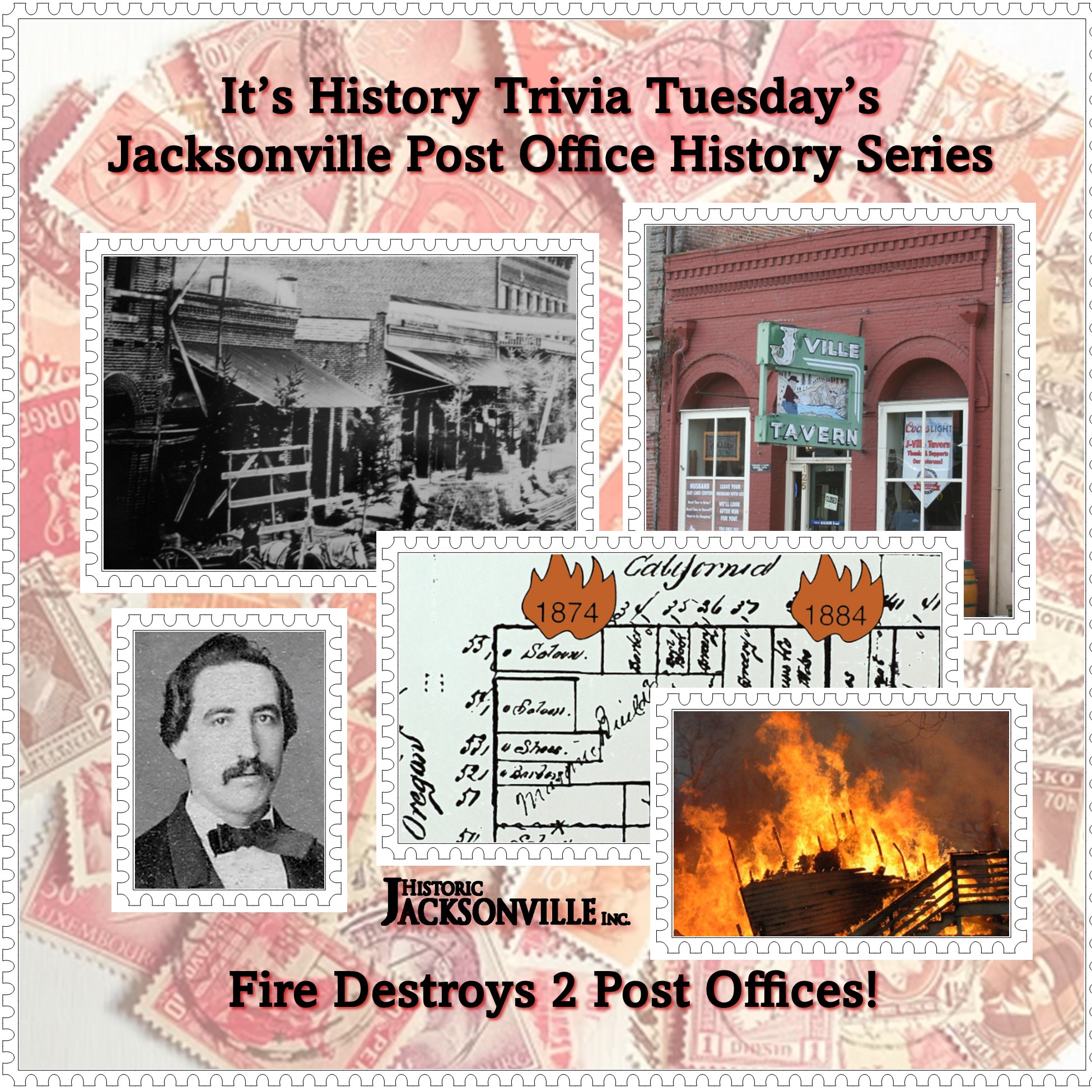

Post Office #5

We’re continuing to track the history and multiple locations of the Jacksonville post office, the oldest continually operating post office in Jackson County and the only one not a substation of Medford.

Postmaster Max Muller saw major fires burn 2 of the post office buildings he supervised. After the 1874 fire he moved the post office to 125 W. California (now the J’ville Tavern), which had been constructed as a “fire proof” brick building. But fire again burned the post office building in 1884.

The fire had originated in the New States Saloon (the current site of Redman’s Hall and Boomtown Saloon) and was not long in reaching the post office store. The building may have been fire proof, but the store’s contents were not. The fire entered the cellar from the adjacent building and “raged inside.” However, the iron coverings over the store’s windows and doors were kept closed “and the flames allowed to spend their forces.” The brick walls remained intact, and 5 months later the post office store was again ready for occupancy.

Post Office #6

It’s the next installment in our saga of the Jacksonville post office, the oldest continually operating independent post office in Jackson County since being established in 1854. In July 1888, the Democratic administration appointed Henry Pape, Sr. to the position of Jacksonville postmaster. Pape, one of the town’s substantial German citizens, was a popular saloon keeper.

For almost a decade, Pape was a partner in the News State Saloon, but by 1876 Pape had set up his own saloon in the new Masonic Hall building at the corner of California and Oregon, originally the site of the notorious El Dorado Saloon. In May of 1877, the “Democratic Times” noted that “Henry Pape has a snug little corner in the Masonic building and a stock of good material in fine order. He is as jolly and sings as well as ever.”

We can’t attest to his singing, but Pape was also reported at various times as being “a practical mechanic,” having mining interests, and serving 2 terms as Jackson County Treasurer and several years as Jacksonville City Treasurer. In 1888 Pape was appointed Jacksonville Postmaster—and he promptly moved the post office to his saloon. Pape was apparently both popular and capable since the succeeding Republican administration retained his services as postmaster for at least another 2 terms.

Would you like a beer with your letters?

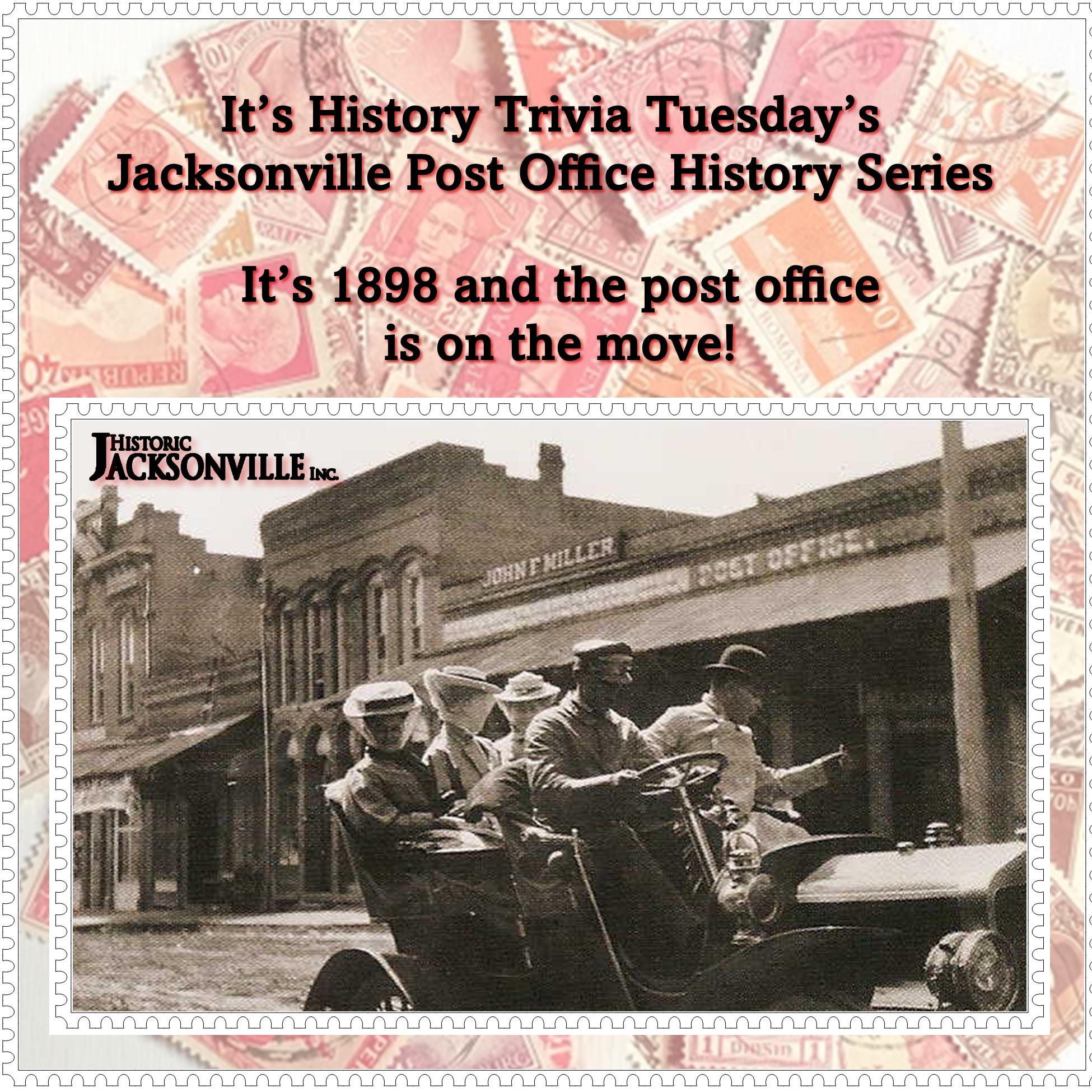

Post Office #7

It’s 1898 and the Jacksonville Post Office has moved again! John F. Miller, Jr. is the new Postmaster, and he’s moved the post office one building—from Pape’s saloon in the Masonic building into Schumpf’s barber shop next to Miller’s hardware store. By 1907, the barber shop has been replaced by a millinery shop. Currently this building at 157 E. California Street is occupied by Rebel Heart Books. Hair, hats, or books—the post office was in a very “heady” location!

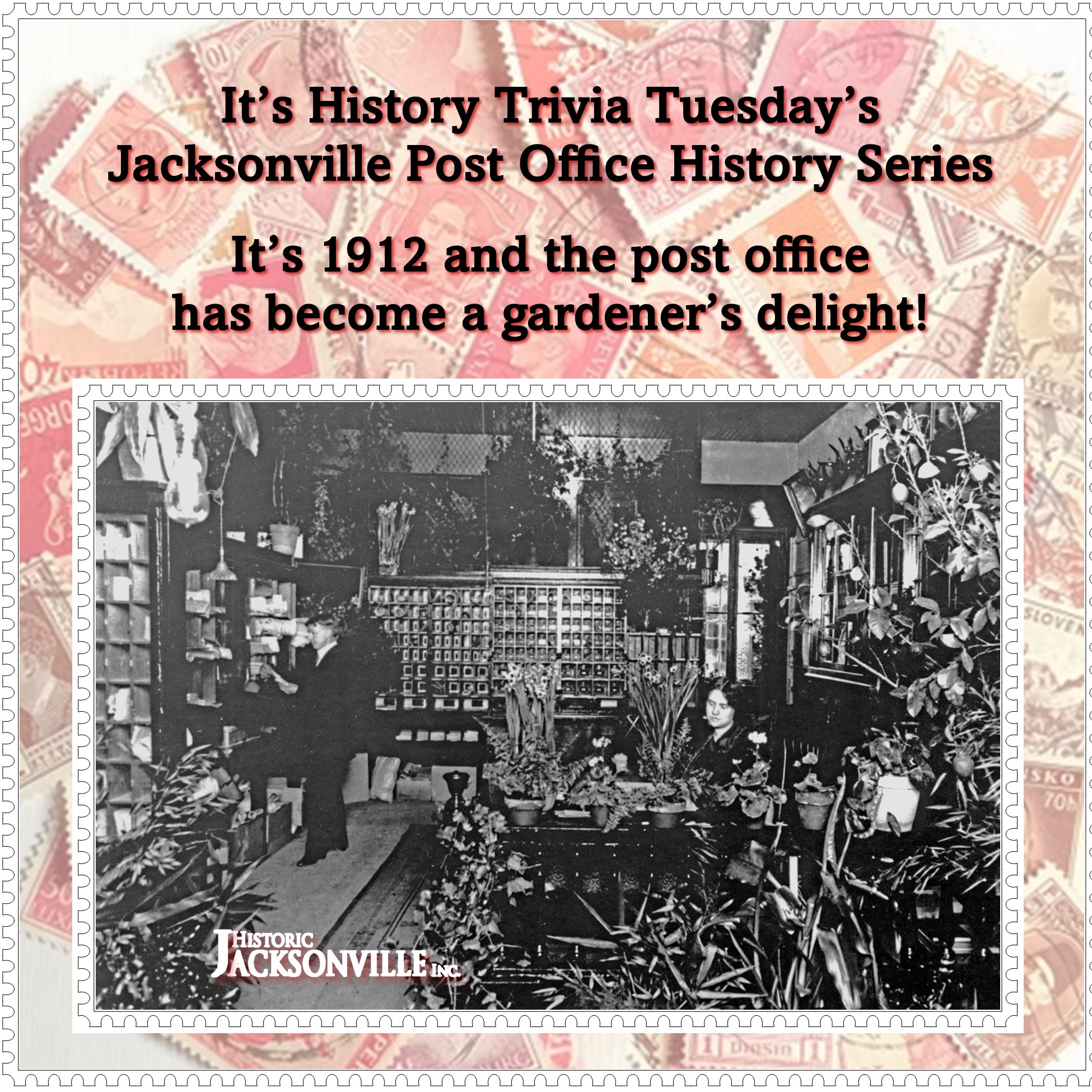

Post Office #8

Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is continuing its saga of the Jacksonville post office, the oldest continually operating independent post office in Jackson County! It’s also 1912, and Postmaster John F. Miller has moved the post office into his former hardware store at 155 W. California Street, now home to the Jacksonville Company. Miller’s father had been Jacksonville’s first gunsmith, and this 1874 brick building had originally housed his father’s “Hunters’ Emporium.”

However, John was more of a gardener. In addition to installing copper lock boxes and special windows for money orders, registry business, and general delivery, he decorated the building with flowers and plants “hanging from the ceiling and piled in corners.” The “Jacksonville Sentinel” described it as a “combination of a parlor and a greenhouse.”

The U.S. Postal Service authorities were not as impressed and eventually required Miller to remove the plants.

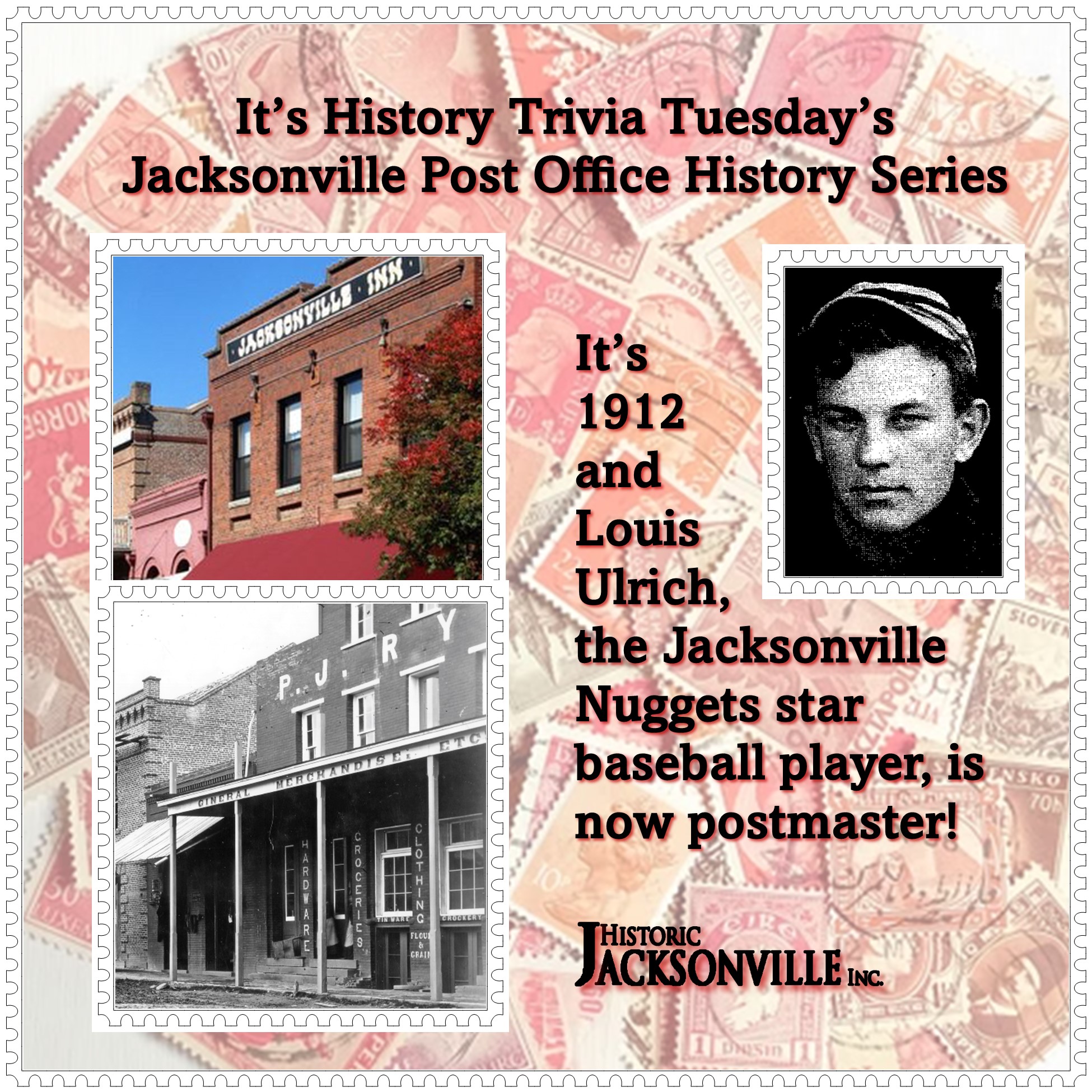

Post Office #9

We’re continuing our saga of the Jacksonville Post Office, the oldest continually operating independent post office in Jackson County. In late 1912, Postmaster John F. Miller, Jr. chose to take a break from his duties after 14 years of service. His wife Mabel was appointed Postmistress in his stead but died suddenly within weeks of being named.

The grieving widower resumed the role on an interim basis until June 1913, when Lewis (Louis) Ulrich, the Jacksonville Nugget’s “pet” baseball player, was appointed to the position. For convenience, Ulrich moved the post office into space in the P.J. Ryan Building (now the Jacksonville Inn) next to his flour and feed store.

Apart from his business and baseball interests, Ulrich also took an interest in politics. In 1906 he had served as Assistant County Treasurer, and in 1920 he became Col. Herbert Sargent’s “lieutenant” in Jacksonville’s battle to retain the county seat. He gladly performed the duties of “toastmaster” at the gala that celebrated the town’s short-lived success.

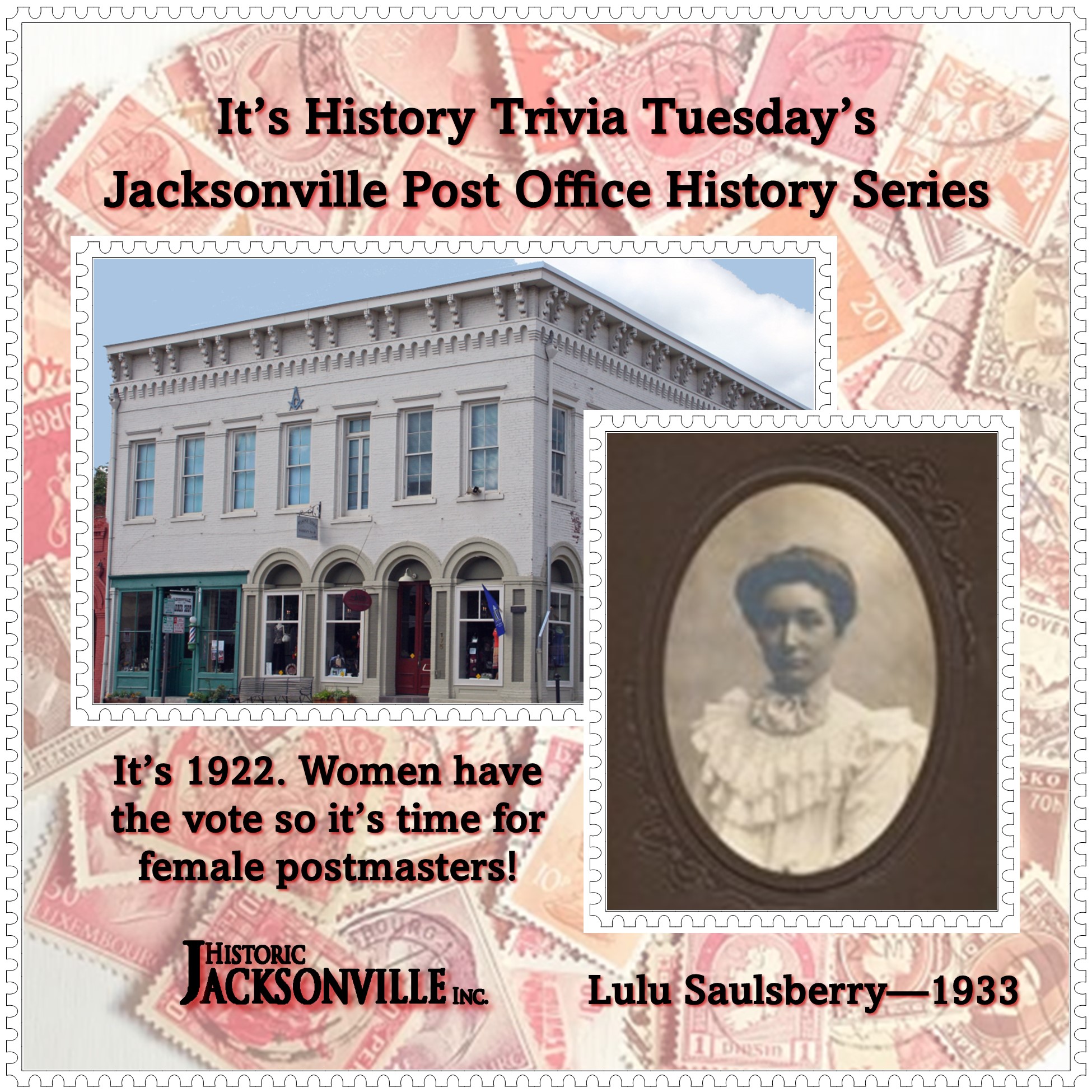

Post Office #10

And so we continue the saga of the Jacksonville Post Office. Beginning in 1922, Jacksonville employed an extended series of women post masters: Flora Thompson (1922-27), who had previously worked as a stenographer in the sheriff’s office; Alice Hoefs (1928-1932), formerly a saleswoman; Lulu Saulsberry—shown here (1933); Ella Eaton (1934-38), who later became the town telephone operator; Ruth Hoffman (1939-1942), Eastern Star Matron; and Mary Smith Christean (1943-1952).

Shortly prior to Saulsberry’s appointment, the post office was moved back to the Masonic Hall. And there’s still more to come, so stick with us for a few more weeks as we wend our way through the story of the oldest continually operating independent post office in Jackson County!

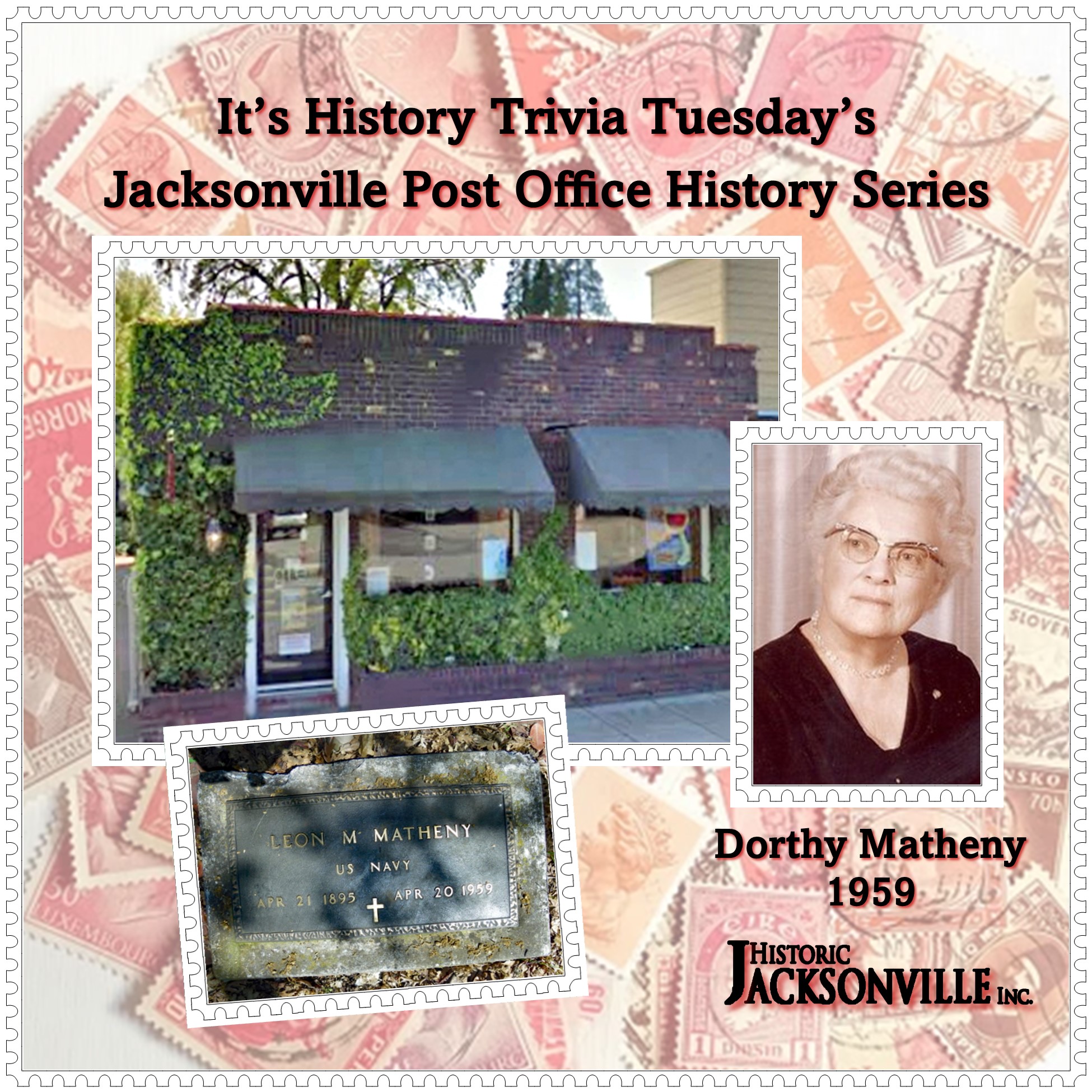

Post Office #11

We’re into the 1950s so are nearing the end of the wandering Jacksonville Post Office saga. Around 1954, the post office was again relocated—this time 2 ½ blocks down the street from the Masonic building to 220 E. California. A Jacksonville resident who grew up here remembered the move clearly. “It was my job to pick up the mail on the way home from school. The boxes had dial combinations, and I had to learn a new one. I loved Wednesdays when the Saturday Evening Post came!”

The Postmaster during this period was Leon Matheny. When he died suddenly in 1959, his niece-in-law, Dorland Matheny was appointed Acting Postmaster.

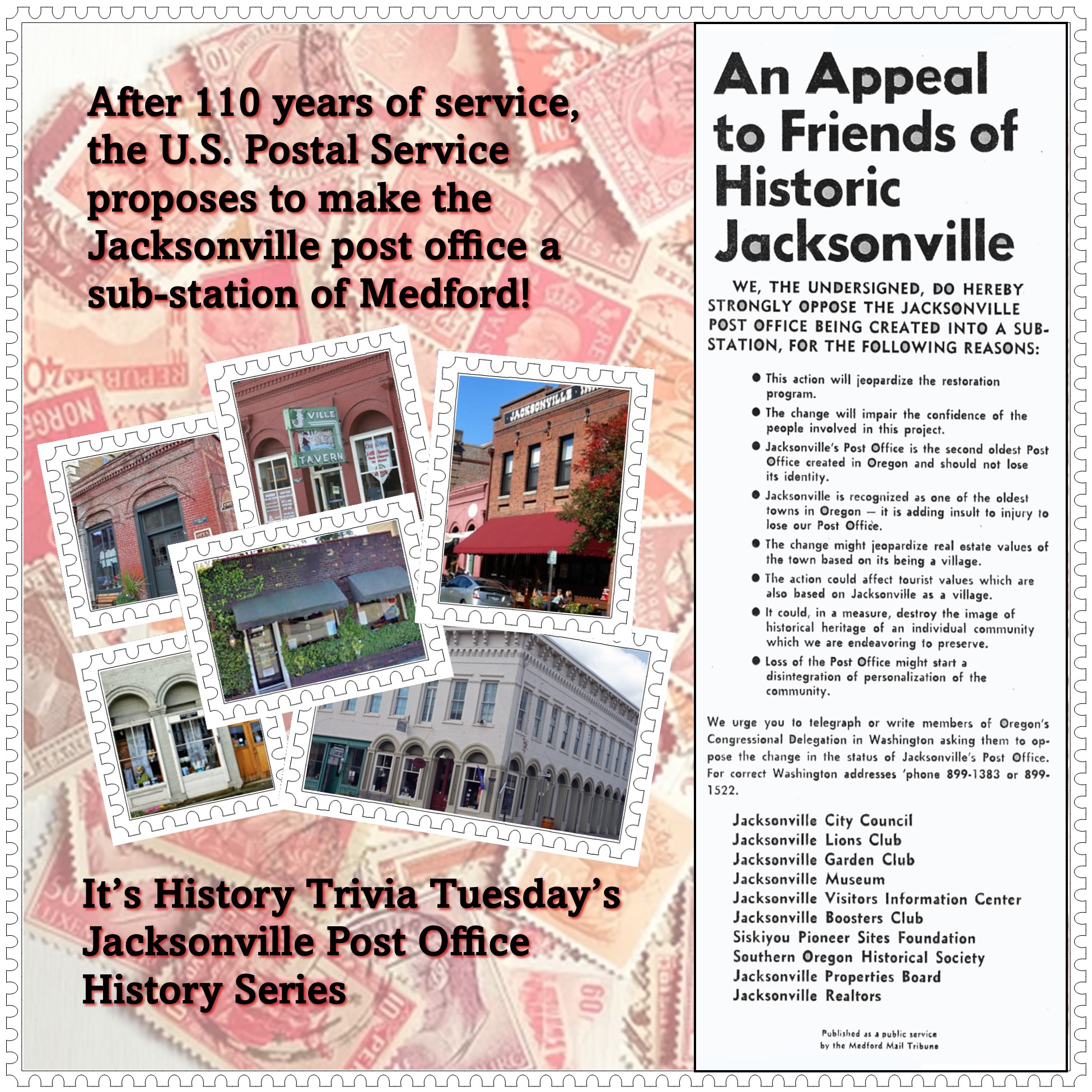

Post Office #12

When Jacksonville Postmaster Lynn Houston Valentine resigned in 1963, the Post Office Department proposed to make Jacksonville a substation of Medford, citing the potential for improved service for less money. (Does this sound a lot like mail currently being sent to Portland for processing?)

Residents, businesses, and organizations actively opposed the proposal, saying they were perfectly happy with current service. Opponents published an “ad” in the October 22, 1965, Medford Mail Tribune as “An Appeal to Friends of Historic Jacksonville.” Signed by the City Council, the Lions Club, the Garden Club, the Jacksonville Museum, the Visitors Information Center, the Boosters Club, the Properties Board, the Realtors, the Siskiyou Pioneer Sites Foundation, and the Southern Oregon Historical Society, it cited the town’s uniqueness, its efforts to preserve historic heritage, and the post office’s role as a focal point for residents, the potential for a change to jeopardize the town’s restoration program, the impact on real estate values, and the impact on tourism.

The proposal’s opponents ultimately prevailed, and the Jacksonville Post Office remains the oldest continually operating independent post office in Jackson County, Oregon!

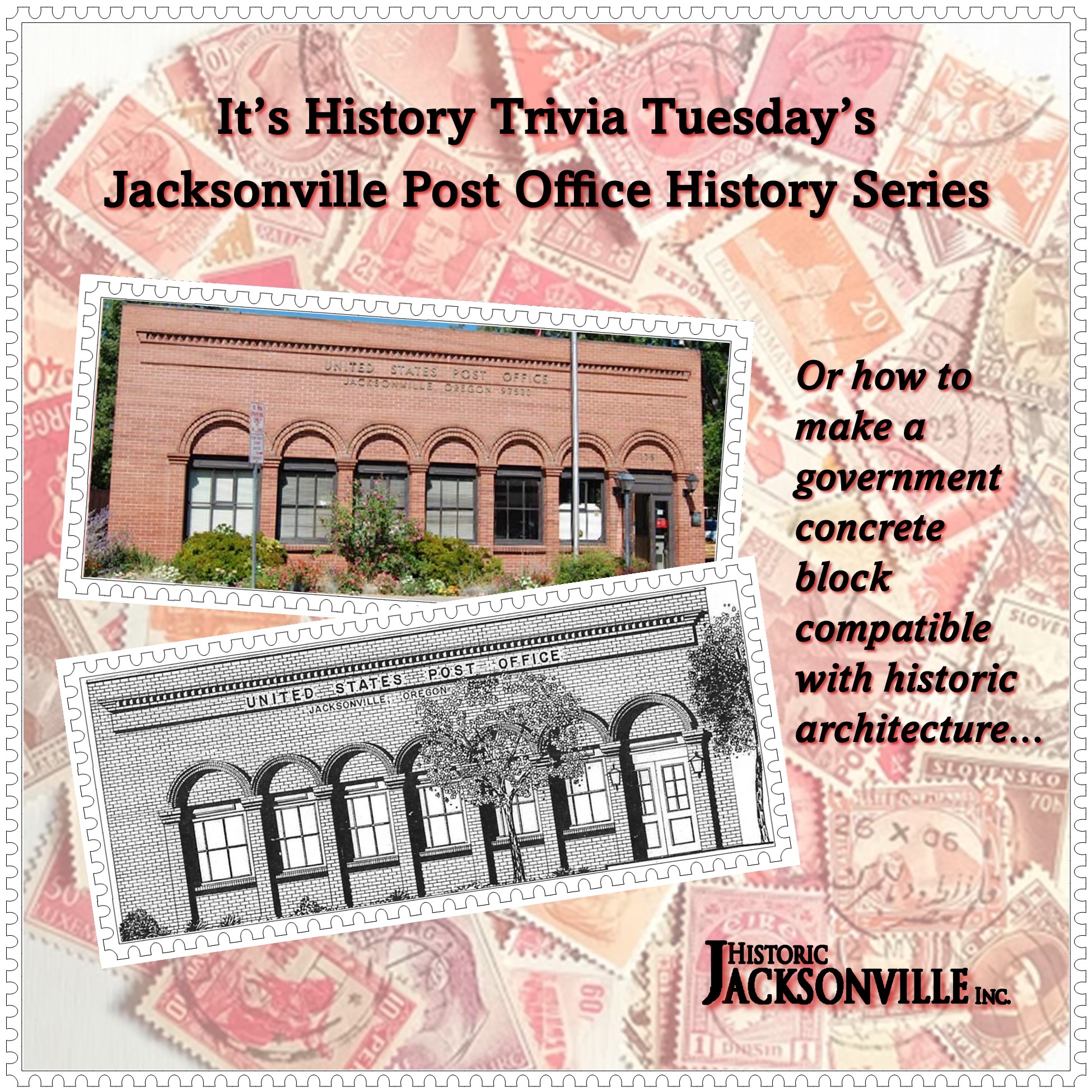

Post Office #13

We’re almost to the end of Jacksonville’s wandering post office saga!

After the “Friends of Historic Jacksonville” successfully retained the Jacksonville Post Office’s status as the oldest continually operating independent post office in Jackson County, the postal service decided it needed a new, larger building. In 1967 they chose a lot on N. Oregon Street by the old train depot, but they proposed a plain, government-designed, cement block building—a far cry from Jacksonville’s historic architecture and the town’s new standing as a National Historic Landmark District.

When the Regional Postmaster in Seattle refused to answer phone calls or telegrams from local officials, Robertson Collins, the individual who had spearheaded Jacksonville’s restoration went to work. Marshaling the support of Eric Allen (editor of the Medford Mail Tribune), Alfred Carpenter (Carpenter Foundation), Curly Graham (Jacksonville Mayor), Glen Jackson (head of the Oregon Department of Transportation), and Oregon Senator Mark Hatfield, the foundation submitted a design by local architect Jeff Shute that created a brick sheath over the proposed building, retaining its basic design but compatible with existing historic structures.

Once the proposal was approved, the Regional Postmaster was set up as the hero. In planning the building’s dedication ceremony, Jacksonville Mayor Graham noted, “There is no end to the good you can do if you don’t care who gets the credit.”

Follow Historic Jacksonville, Inc. (historicjville) on Facebook and Instagram (historicjacksonville) and enjoy weekly Jacksonville history trivia. Explore a treasure trove of Jacksonville history on our website at www.historicjacksonville.org.

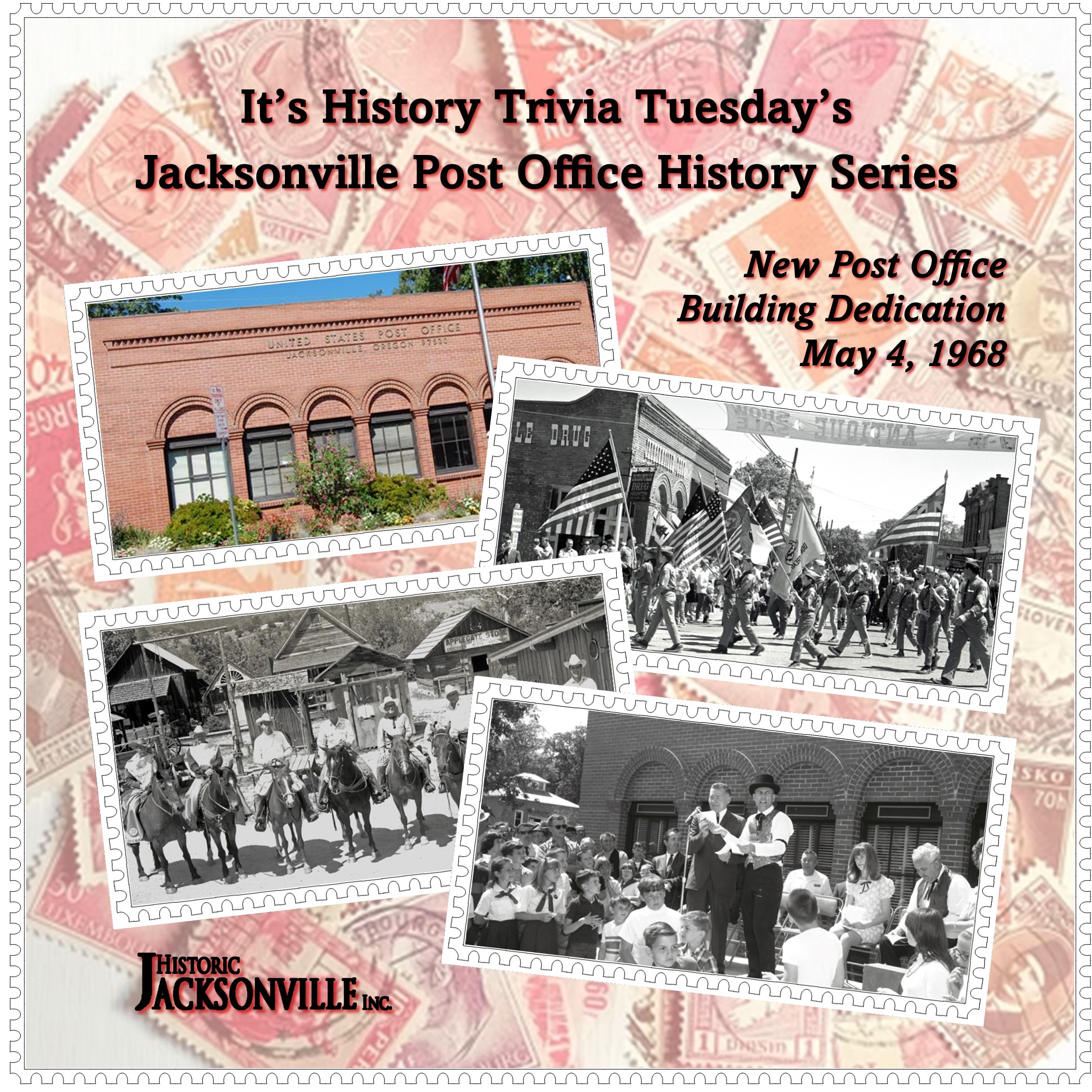

Post Office #14

We’ve finally come to the end of our Jacksonville Post Office saga after chasing the post office’s location beginning in 1854 through most of the buildings in downtown Jacksonville. The structure current residents know as the town post office, located at 175 N. Oregon Street, was officially dedicated on May 4, 1968. And what a celebration it was!

The all-day event kicked off with a “buckaroo breakfast” at the original Pioneer Village, a coffee for U.S. Senator Wayne Morse, a picnic lunch on the grounds of the Jacksonville Museum (now the City offices), followed by a parade from the Museum to the new post office building. The dedication ceremony included speeches by Mayor Curly Graham, Senator Morse, the Regional Post Office Director, and other dignitaries. Morse also dedicated a flag that had flown over the Post Office Department in Washington D.C. to Jacksonville Postmaster Clarence Williams.

A highlight was Pony Express riders delivering mail bags containing congratulatory letters from the mayors of Gold Hill, Central Point, Rogue River, Eagle Point, Medford, Phoenix, Talent and Ashland.

But the day wasn’t over! An open house for the building followed along, with a Britt Society antique show and sale. A dance in the ballroom of the U.S. Hotel finally ended the celebration. It was a very fitting day for the oldest continually operating post office in Jackson County—170 years and counting!

Sexton’s Tool House

In 1863 R. Sergeant Dunlap was appointed the first sexton of Jacksonville’s Pioneer Cemetery. He served in that capacity for many years – maintaining the cemetery grounds, selling plots, digging graves, and keeping the cemetery records. However, what’s known as the Sexton’s Tool House at the top of Cemetery Road was not constructed until 1878. The tool house also doubled as a mortuary. An underground vault provided storage for bodies when the ground was too frozen or too soggy to dig.

Voting

Today is not only History Trivia Tuesday, it’s Election Day! Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is taking the opportunity to remind everyone of how voting has been a hard earned right, one not to be ignored and one to be exercised with thoughtfulness. In 1789, the U.S. Constitution gave property-owning or tax-paying white males the right to vote—only 6% of the population. It was another 67 years (1856) before most states adopted universal white male suffrage. In 1870 the 15th Amendment to the Constitution prevented states from denying males the right to vote on grounds of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude”—but it did not prevent them from disenfranchising racial minorities and poor white voters through poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and other restrictions applied in a discriminatory manner.

Oregon gave women the right to vote in state elections in 1912, but it was 1920—8 years later and 100 years ago—when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified giving (white) women the right to vote in national elections as well.

In 1964, poll taxes were prohibited as a condition of voting and in 1965, the Federal Voting Rights Act protected voter registration and voting rights for minorities. But that did not eliminate voter discrimination with some states still choosing to limit polling places, voting hours, and access to absentee ballots among other things. In 1971, voting age was lowered to 18—if you were old enough to fight for your country, you were old enough to vote. And in 1986, service personnel and U.S. citizens living overseas were given the right to vote in federal elections.

On November 7, 2000, Oregon became the nation’s 1st all vote-by-mail state—if you have an address, you receive a ballot. However, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act, paving the way for states and jurisdictions to enact restrictive voter identification laws. 23 states created new obstacles to voting. Oregon did the opposite. In 2016, Oregon’s Motor Voter Law took effect, automatically registering to vote anyone applying for or renewing a driver’s license.

As individuals, we may have different visions of what we want our future to be, but Oregon has chosen not to limit our citizens’ participation in the conversation about that future. Historic Jacksonville looks forward to a time when we will again be able to talk—and listen—to each other in search of the unity and compromise that made us the United States of America.

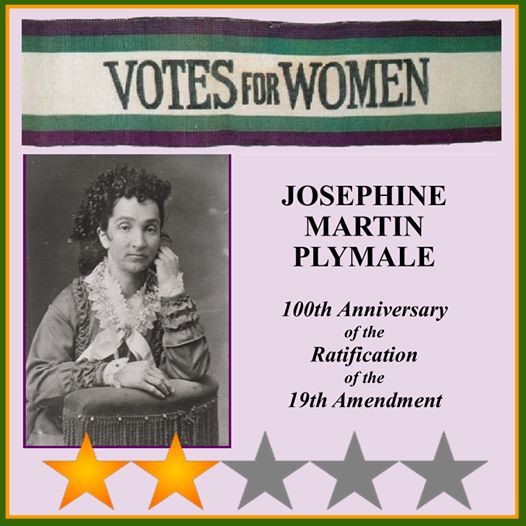

Women’s Suffrage #1

Since August is Women’s Suffrage Month marking the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is using the opportunity to recognize a Jacksonville suffragette—Josephine Martin Plymale. Josephine was in many ways a product of her time. She crossed the Oregon Trail with her family in a covered wagon, came to Jacksonville at age 17 as a teacher, and a year later married William Plymale. However, Josephine also defied the standards of her day.

In a time when anti-suffragists claimed women had no time to vote, Josephine raised 12 children and worked in the family livery business; became an orchardist and was a frequent speaker at Granges and agricultural societies; and was a journalist and served as Vice President of the Oregon Press Association. She was Vice President of the Oregon State Women’s Suffrage Association, described as “one of the most active workers in the Women Suffrage field…anywhere.” She was such an active suffragist that she once had an angry mob outside her Jacksonville home.

In 1892 Josephine officially filed for the position of Jackson County Recorder, but her name never appeared on the ballot. Not to be denied a role in politics, she obtained the position of committee clerk for the Oregon State Legislature and 2 years later clerked for the senate chamber. Josephine took her 2 youngest daughters with her to Salem to give them a taste of politics and to learn how laws were made.

Josephine died in 1899 at the age of 54. She never realized her political ambitions or the right to vote. But her daughters did. Oregon gave women the right to vote in 1912—8 years before the U.S. afforded them that privilege.

Women’s Suffrage #2

August 18, 2020 It’s the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that gave (white) women the right to vote. But Oregon had an 8-year jump on the nation—the state granted women voting rights in 1912. One of the foremost leaders of the suffrage movement in the West was Oregon’s own Abigail Scott Duniway—teacher, author, newspaper publisher, and lecturer. Because of her efforts she was given the privileges of drafting the state’s Equal Suffrage Proclamation and being the first woman in Oregon to vote. Duniway made multiple trips to Jacksonville during her voting rights campaigns, but her strong determination and outspoken manner were not always well received by the local menfolk. During an 1879 tour, when an inflammatory editorial she had written was made known, she was burned in effigy and pelted with eggs. Abigail laughed it off saying, “Only one egg hit us and that was fresh and sweet.”