|

A Virtual Walk Through Jacksonville History

Stop 25: Chinatown

We’ve already mentioned that the intersection of Oregon and West Main Streets was Jacksonville’s original business district. It also was Oregon’s first “Chinatown.”

Jacksonville began in the late winter of 1851-1852 as Table Rock City, a mining camp. The discovery of gold in Daisy and Jackson creeks brought Chinese, along with those from around to world, to Jacksonville. Most of the initial buildings along West Main were tents or hastily erected rough wooden structures built from easily harvested local timber.

Jacksonville Chinatown, West Main Street, @ 1858. SOHS #2464. Jacksonville Chinatown, West Main Street, @ 1858. SOHS #2464.

As the camp rapidly evolved into a town, merchants began to construct “fireproof” brick buildings along Oregon and California streets. By the mid-1850s, Oregon and California streets had become the hub of Jacksonville commerce. West Main provided an opportunity for the Chinese miners entering the area. It rapidly became the Chinese Quarter, a bustling ethnic neighborhood.

So who lived in Jacksonville’s Chinatown and what were their lives like? Let’s take a virtual visit and see what we can learn.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps delineate Chinatown’s footprint as the south side of West Main and the south side of California west of Oregon Street with a few exceptions lying outside of that neighborhood. However, they do not distinguish building uses. Descriptions of life within this footprint are sparse and scattered.

Drawing of Chinese Quarter based on 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Drawing of Chinese Quarter based on 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map

Following the 1848 discovery of gold in California, most early Chinese residents came to America in search of “Gold Mountain.” Many were peasants from Quangdong (Canton) Province, seeking to escape the political turmoil of the time and to provide greater opportunity for their families remaining at home. They came under contract to Chinese labor bosses who supplied mine owners, and later the railroad, with cheap labor. There were also those who came on their own. As mining moved north, so did they. Most immigrants were men, many of whom sent most of their wages home to their families in China. Most were laborers, some worked house servants, and a few were businessmen. Prior to 1882, of the several hundred Chinese listed in the Jacksonville area, less than two dozen were women.

|

|

|

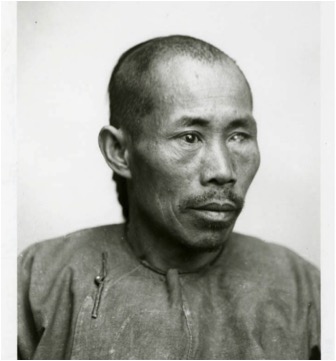

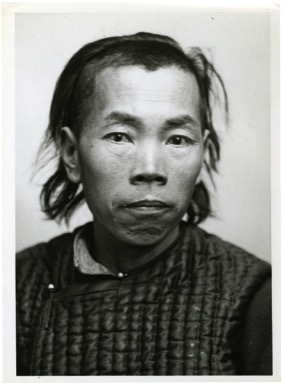

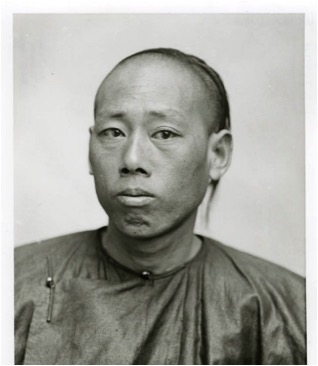

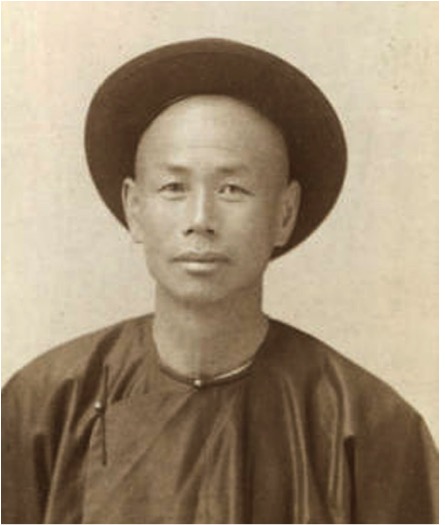

| Photos of Chinese Men courtesy of Southern Oregon University Hannon Library, Peter Britt Collection. |

And from the time of their arrival, the Chinese dress, lifestyle, and hard work angered and frighted the White miners and settlers.

Father Francis Xavier Blanchet, priest at Jacksonville’s St. Joseph’ Catholic Church, wrote that the Chinese “all wear the same costume from a dignitary to a daily laborer; a skull-cap, a collar, a long blue coat, a belt, blue trousers, white stockings and cloth shoes with paper soles.” He described the traditional Manchu hairstyle as “a shaven head with only a tuft of hair left from which a long queue hangs down their backs.” He further depicted the Chinese diet as rice, rice, and more rice, eaten with two sticks of ivory or bamboo.

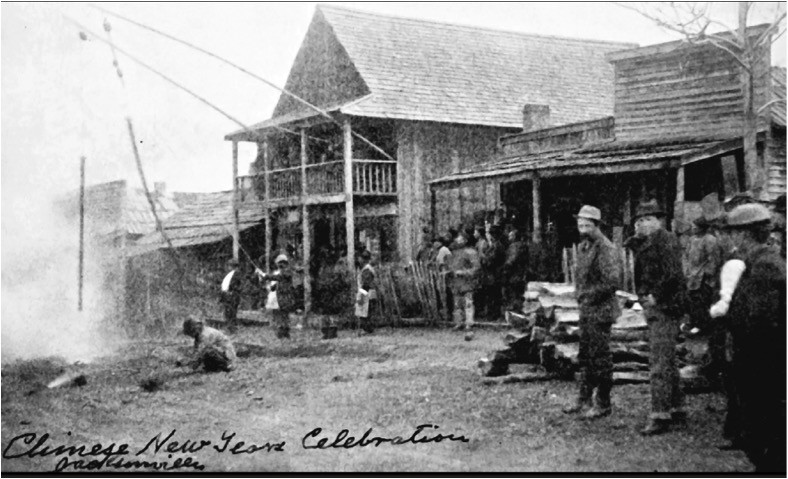

Customs and celebrations were also found strange and distasteful, in direct opposition to an “American lifestyle.” The primary ritual was the Chinese New Year that took place on the first full moon of late winter. Although many residents found the celebratory food a “great stink” and the firecrackers and oriental music a cacophony of noise, others, particularly, children, enjoyed the celebrations.

Chinese New Year Celebration. SOHS #1505. Chinese New Year Celebration. SOHS #1505.

A 2016 report, “Rising from the Ashes: Jacksonville Chinese Quarter Site,” prepared by the Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology (SOULA) for The Oregon Department of Transportation affords most of the insights we have into the Chinese community. Census records, newspapers, and other primary documents from the 1800s provide a sketch of the neighborhood.

Eni Yan. Beekman Housekeeper. SOHS #869 Eni Yan. Beekman Housekeeper. SOHS #869 |

While there may have been several hundred residents in Chinatown at various times, it appears they occupied no more than two dozen buildings. The 1860 census lists most of the residents as ‘miners’ with a ‘clothes washer’ and a few cooks noted. Many would have been working in the mines during the week and only sporadically resident in the Chinese Quarter. In addition to homes and group lodgings, several businesses and services were active within the quarter.

Within a decade, a variety of professions are noted, with residents working in occupations serving a variety of community functions on both sides of the Chinese Quarter lines. While mining remains the most prevalent occupation, more residents are listed as cooks and domestic servants (with some living in the neighborhood and others on site with employers).

The number of laundries expanded by the 1870s, most of which served the white residents of Jacksonville and the surrounding area. However, while the laundries might have relied on white customers, these businesses also served as small community hubs and provided social services such as brokering employment opportunities. Several occupations are also listed that would have primarily served the Chinese community, including a butcher, two barbers, a trader, hotel keeper, a carpenter, a handful of gamblers, and a doctor named Chung Kee.

While the diversity of occupations was reduced by the 1880s (as was the population in general), the census indicates that Chinese residents were still actively employed at a nearby hotel and in several laundries around town.

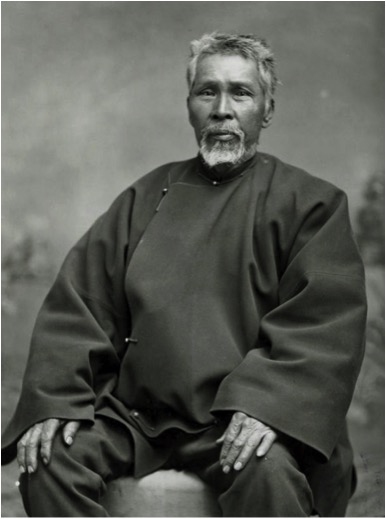

Gin Lin Gin Lin

Southern Oregon University Hannon Library, Britt Collection |

And there was certainly additional interaction and relationships between the Chinese and Whites in addition to Chinese who were employed as cooks or servants. Several Chinese men lived on or near the Peter Britt estate, perhaps tending his gardens and orchards. He is said to have been their employer and banker, helping with finances. There are also several Chinese signatures in the Beekman Bank registers. One Chinese labor boss, Gin Lin, is reputed to have had over $2 million deposited with Beekman. Lin also reportedly had a relationship with local contractor David Linn, greeting him as “cousin.” Because most merchants sold goods “on account,” there are also records of those Whites who willingly traded with the Chinese.

However, the Chinese were always discriminated against. Chinese living in Oregon were initially denied the right to vote, and only the Chinese that were residents at the time of the adoption of the Oregon Constitution (1857) could own real estate or mining claims. They were left to take over secondhand claims, then were resented when their labor dug out gold that had been overlooked.

Oregon further targeted Chinese livelihoods, in 1862 passing legislation stating that “all Chinamen … engaged in trading, buying and selling foods, chattel, merchandise and all kinds of livestock and every kind of trade and barter among themselves in the State of Oregon shall pay for each privilege the sum of fifty dollars per month.” That same year the Oregon Poll Tax law was established levying an annual poll-tax of five dollars against “Chinamen” as well as other minorities. Jackson County levied an additional poll tax of $3 per “Chinaman” per quarter. City records noted licensing fees collected from Chinese peddlers Ah Kee, A. Chan, and A. Chow.

Prior to 1866, the Chinese were not allowed to testify in court against Whites who stole from them or assaulted them. Additional laws were created in an attempt to curb Chinese population growth. Laundries were a common Chinese enterprise and became a particular target for local municipal laws. In 1881 Jacksonville passed an ordinance stating that “every person or persons who shall set up or keep as a business, any washhouse or laundry within the corporate limits of Jacksonville, shall pay a quarterly license of no less than five dollars for keeping or setting up such a business”

We have names for some of these individuals. Laundry licenses were taken out under the names of Lim Wang, Toy Loy, Toy Kee, Chin Chin, and Kwong Woo.

The death knell may have been the U.S. the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882. It prohibited any more Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S. and denied citizenship to those already living here. It made many Chinese residents unable to support themselves. Many returned to China, and Jacksonville’s Chinatown became derelict and mostly deserted.

Jacksonville’s general population continued to decline due to the railroad bypassing the town in 1887. Then most of Jacksonville’s Chinese Quarter burned in the fire of 1888 that started at David Linn’s furniture factory at the corner of California and Oregon. Whites bought up much of the remaining property. By the turn of the 20th century, the Chinese population had shrunk to just a handful of residents along “A Street” (West Main Street).

Between 1882 and 1924 a long series of legislation was enacted with the intent of driving the Chinese from the United States. Finally, the Exclusion Act of 1924 eliminated all Asians ineligible for citizenship.

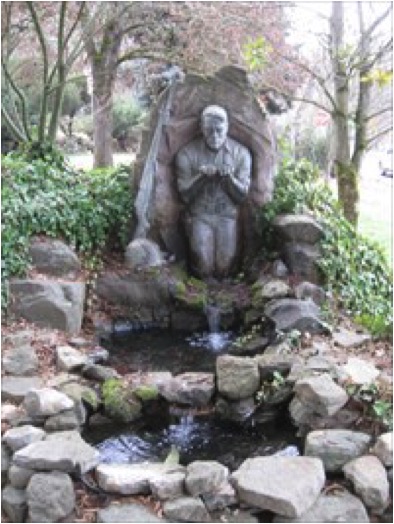

Today, what was once a thriving Chinese Quarter is now home to commercial buildings, residences, and Jacksonville’s Veteran’s Park.

|

|

West Main Street, Jacksonville.

Photo Source: Carolyn Kingsnorth |

Veterans Park, Jacksonville.

Photo Source: Waymarking |

Sources Cited

Excavations.” 2016 SOULA research report prepared for The Oregon Department of Transportation

Kay Atwood, Minorities of Early Jackson County, prepared for Jackson County Intermediate Education District, 1976.

Southern Oregon University Hannon Library, Peter Britt Collection.

François Xavier Blanchet and Edward J. Kowrach. Ten Years on the Pacific Coast. Ye Galleon Press, 1982.

|